Part Two: New Opportunities, New Stress

In the Gulf region, Dubai has been a forerunner in the transformation towards a neoliberal market of skills and hands. Gulf countries generally require foreign workers to find a citizen sponsor (kafil) who acts as their legal guardian. In the past, this meant that workers would typically be hired by labour agents in their home countries, already arrive with contracts and residence permits, and work for one company until their eventual departure. Seeking jobs from within the country and even changing jobs was difficult. Stories of workers deprived of their passports and salaries, and stuck in inhumane conditions unable to return to their home countries, are common.

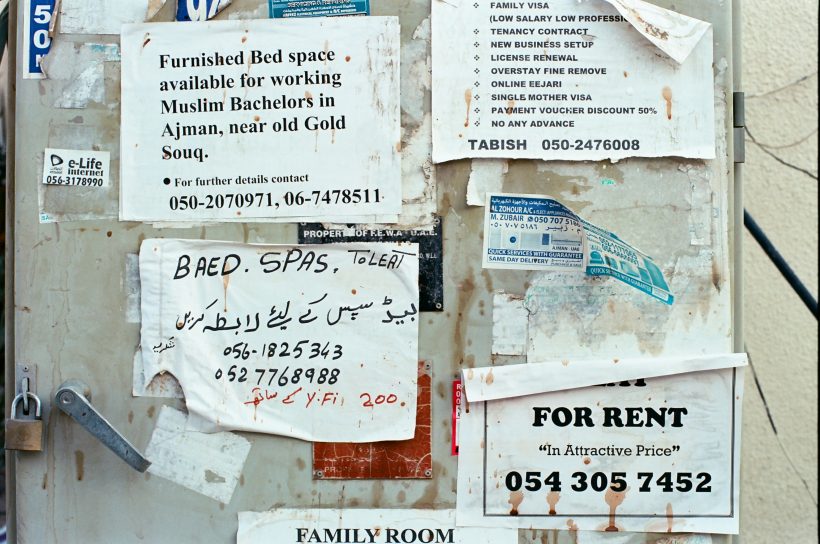

In the 2000s, the United Arab Emirates became the first Gulf state to allow jobseekers to arrive on tourist visas, which they could transfer to residence permits once they found work. Tourist visas have become an increasingly important avenue for migrants on all income levels, despite the up-front expenses for travel, accommodation, and cost of living, which easily exceed the fees collected by labour agents. At the same time, the UAE has eased sponsorship rules (kafala). Today, the company that hires somebody can itself act as the sponsor, and a transfer of sponsorship is no longer dependent on the sponsor’s goodwill, but has become a routine administrative transaction – for a fee.

Countless people were out of work, mostly stuck in their home countries, lacking the means or not willing to take the risk to return.

This emerging new system of migrant labour has been an improvement for many jobseekers. It is also in the interest of Dubai’s trade-oriented economy, which requires a flexible labour market that could not always be fed by the rather slow and heavy system based on migrants recruited abroad on two-years fixed-term contracts. This transformation was also fuelled by the 2008 financial crisis that hit Dubai hard. Although the UAE still is a welfare state towards its citizens, who can expect public sector employment at good conditions, much public sector work, be it at airports or government offices, is today outsourced to private companies hiring both migrants and nationals under more precarious terms.

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a sudden boost to the neoliberalisation of the job market ever since the UAE stopped issuing work visas abroad in March 2020 (with few exceptions). The only way to get a residence permit today is by being hired in the country and directly by the prospective employer. In the autumn of 2020, when economic activity began recovering, the unavailability of work visas resulted in a simultaneous lack of jobs and labour. Countless people were out of work, mostly stuck in their home countries, lacking the means or not willing to take the risk to return. At the same time, there were companies desperate to find employees whom they could only hire inside the country. This presents an opportunity for those who have the resources to be there, and especially those who still have a valid residence permit with which to return to Dubai. But it also comes with new risks and uncertainties.

T. soon had to give up his plan A of getting back to his old job. After a promising start of the tourist season in December, in January already it did not look like operations would further pick up for a while. And so he began applying for all customer service jobs that were on offer, submitting his CV to application systems online and attending interviews wherever he could. Number one on his list was a competing company at the airport. Many of his colleagues had gone there. He was invited to an interview at the company’s accommodations, and I went along. He was offered the job, but colleagues there warned him that overtime was largely unpaid due to irregular shift schedules, and that the housing was clean but had unpleasant restrictions – there were no kitchens, workers were not allowed to spend the night outside the accommodation, and if they left it for more than 3 hours in the daytime, they had to show a negative PCR test. Their advice was “keep searching, and only if you find nothing else, then come here.”

T. found it an unbearable load of unknowns.

He had in fact already received a better offer, as customer service agent at an outsourcing company, posted in a government office, but he was uncertain about it. It was a new kind of work profile, and the job came with neither accommodation nor transportation. The pay was better, but he could not know how much better because it partly depended on commissions for customer transactions. T. found it an unbearable load of unknowns. He might not have opted for it, had it not been for relatives and friends working in middle class jobs in the Dubai metropolitan area, who told him that it was a much better job than the one at the airport. Even so, he was hesitant. He called a lawyer friend who ensured that the contract he was offered was indeed unlimited, and that he could quit again without contractual fines. He began looking for a bed in a shared accommodation, estimating commuting expenses and walking distances from the metro station – in the summer heat, walking distances are a major issue –, price levels in supermarkets, and filled sheets of paper with calculations. He figured out that in the first six months, his net savings would be less than at the airport, but afterwards better. Then the company called him and asked if he could start in two days. He bought a suit (required for the job, and an additional expense), and started working.

I had hoped that this might relieve the intense stress he was under, but relief would not yet come. His predecessor at the job, who was supposed to train him, was absent for several days. He feared making mistakes in financial transactions, and was worried about how to interact with Emirati nationals (all of them women) who dominated the workplace. His colleagues were surprised that he had no previous experience at government offices. The outsourcing company hired him either because it could not find experienced workers, or because unexperienced workers were much cheaper. Either way, it was a lucky break for T. who otherwise might not have gotten the job.

T. has good reasons to remain nostalgic for the good old days of contract visas, orderly conditions, and predictable monthly salaries.

T. had acknowledged to me and others that he felt uncertain because he had never been a jobseeker before. In Egypt he was a low-paid civil servant. His previous migrations to the Gulf had been organised by labour agents in Egypt; he had arrived with a contract and a visa, and returned to Egypt at the end of his contract. He listed to me what contributed to the overwhelming pressure he felt: there was the historically new situation of Covid; he had to become a jobseeker for the first time in his life; he took a job in a sector where he hadn’t worked before; and he was moving for the first time to an accommodation that was neither a company camp nor run by a friend from the village.

T. is a quick learner, and it looks like he will soon excel and be successful at his new work. And yet if he had the choice, he would not have left his job at the airport, nor would he have left the less demanding but better paid job that he had held in Abu Dhabi from 2011 to 2013. The latter offered the best pay he has ever earned: 3570 dirhams with accommodation and one daily meal provided, as compared to his airport job that paid 2500 plus up to 500 for overtime per month, with accommodation provided (one euro equals ca. 4.4 AED). New contracts by the competing company at the airport offer a salary of only 2200 AED (following a widespread reduction of salaries by 20-25% in the UAE due to the pandemic in 2020), and overtime is unpaid for the time being. T.’s new job comes with a commission for customer transactions on top of a 2500 dirhams salary (to be increased to 3000 after six months), but he must pay for his own accommodation and transportation. The job will likely provide him his highest earnings so far, but even so he may be able to save less than he could in Abu Dhabi ten years ago due to higher cost of living. And thus T. has good reasons to remain nostalgic for the good old days of contract visas, orderly conditions, and predictable monthly salaries.

The good old days were not that good, however, when it came to the possibility of changing jobs. At his first job abroad in another Gulf country from 2008 to 2010, it was impossible to change jobs. The options were to either complete one’s contract or go home, and the company held his passport. In the UAE in the 2010s, the situation was already better, and changing jobs was relatively easy. However, even today, companies can exert significant pressure on their workers to prevent them from leaving.

Some of T.’s colleagues learned to know it the hard way. When airport jobs were unavailable last summer, they found work at yet another security contractor in Abu Dhabi. Abu Dhabi salaries are higher: for security guards, 2700 dirhams with accommodation included, instead of 2200 in Dubai. However, they discovered that they were being officially hired in Dubai, and thus received a lower salary. The work was tiring and boring (typically standing outdoors at various sites), and they found the bathrooms at the accommodation of unbearably low standard. New job openings emerged at Dubai Airport, and they hoped to be hired there or somewhere else in Dubai. At their previous employer at the airport, which they now remembered with nostalgia, they had had unlimited contracts that they could leave with a one-month notice period. Now, they were stuck in two-year fixed-term contracts and had to pay a contractual fine equivalent to 45 days’ base salary to quit early. They did, but the company refused to accept their resignation.

In late December, I met four of T.’s former colleagues in Abu Dhabi in very good spirits. They had filed a lawsuit demanding an immediate cancellation of the contracts because hiring them in Dubai and posting them in Abu Dhabi was illegal. While we were eating lunch, they received text messages confirming that they had won their case. They were in jubilant mood, already planning where they would want to live in Dubai and speaking of the “girls” they would invite to their future accommodations.

The workers I have met generally appreciated the rule of law that prevails in the UAE. Courts routinely rule in favour of workers in labour cases, and some judges even side with workers who have signed documents waiving claims towards their employers because judges know that workers are often forced to sign, and consider such signatures not binding. That said, the laws organising migrant labour still provide employers ample means to discipline workers. The foremost means of discipline is the threat of a ban from the UAE, which can be issued, among other reasons, due to “absconding”, that is, leaving one’s workplace for more than seven consecutive days. (The Arabic term hurub, literally “escape”, expresses more precisely than the English term the kind of understanding of the employer-employee relation that underlies the law.) And this is what the four men’s employer tried. Only two hours later, the company filed a demand for a ban against them. The lawsuit had no prospect of success, but it prevented them from leaving their company and taking up new jobs, which was an effective punishment. After one month, when some of the job offers they had received in Dubai had already expired, the company finally withdrew the claim for a ban, and began issuing cancellations of contract to the men.

The lawsuit had no prospect of success, but it prevented them from leaving their company and taking up new jobs, which was an effective punishment.

And yet, others I met would have signed anytime for the jobs they were trying to get out of. In Dubai in winter 2020-21, I came across a few people who were desperate to find any work that would come with a legal residence permit to prevent them from slipping into illegality.

In Part Three, we will meet other jobseekers who did not find work as quickly as T., and thus had to resort to other means to stay in the country. Read it here.

See part 1 of the series here.