Arrivals to uncertainty

In mid-December 2020, my friend T. returned to Dubai from Egypt in the hope of getting his old job back or finding new work. His cousin H. and I went to pick him up at the airport.

T. had been out of the country on unpaid leave since the end of August, but he had been out of work since April. He used to work as a customer service agent at Dubai Airport, a work that he found interesting and demanding, as did many of his former colleagues whom I would soon learn to know. Working in security, check-in, customer service and other similar roles, they belonged to a vast proletarian service workforce that ran one of the world’s leading aviation hubs. The nature of their work gave them a sense of cosmopolitan capital and a set of skills that exceeded the financial and contractual status of their work.

The nature of their work gave them a sense of cosmopolitan capital and a set of skills that exceeded the financial and contractual status of their work.

I had arrived a few days earlier on a trip enabled by Dubai’s apparently stable Covid-19 situation in November and December, and the temporary immunity I gained through a mild but long case of Covid in the autumn. Like other anthropologists, I had cancelled all my fieldwork in 2020 due to the pandemic, and I have not learned to do remote ethnography over digital media. I wanted to write about houses that migrants build in their places of origin. But I could not visit those houses, and many of the builders could not continue building them due to the economic crisis that has resulted from the pandemic. And so I travelled to Dubai because it was the one place where I could go and where I knew some people, hoping to find out what other stories there might be to tell.

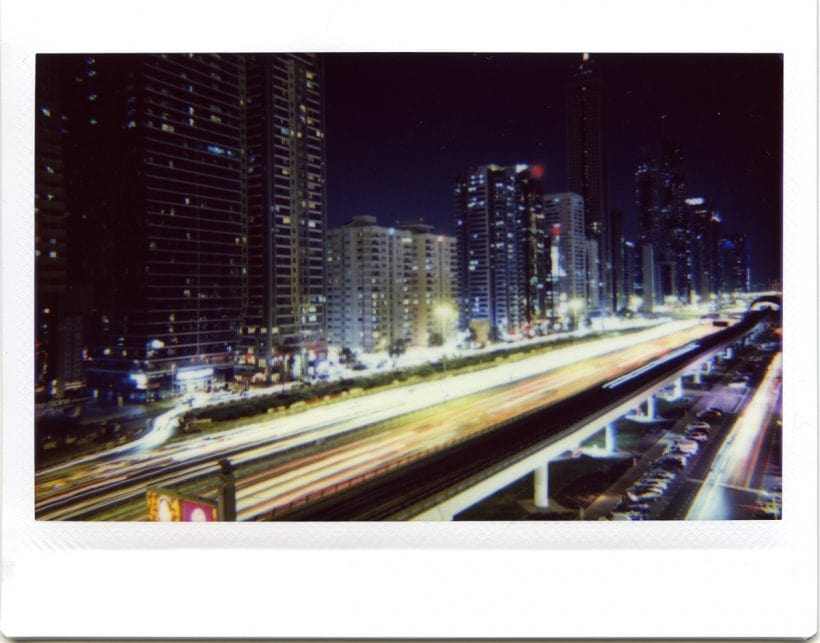

From December 2020 to January 2021, I spent almost two months in the metropolitan area of Dubai (which includes the emirates of Sharjah and Ajman), and I soon fell in love with the plurality of people, and the richness of their stories. I still hope to write about migrants’ homes, and maybe there is also a story to tell about Egyptian-Filipino love affairs. But now, with this essay, I want to tell a more urgent story that is related to the current moment: a great number of people are looking for jobs in the unique situation brought about by the pandemic, while Dubai is transitioning from oil and contract-labour economy to a neoliberal trade hub with a flexible labour market.

Tragically for T. and his colleagues, aviation became the sector most heavily affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. When the United Arab Emirates went into a three-months lockdown in late March 2020, the entire airport was closed. When it was finally reopened in the summer, operations returned at a very reduced scale. Until July, T. had lived without income in the company accommodation, officially on their payroll but jobless and penniless. His colleagues and he relied on private charities for food. In July, T. left the eerily empty company accommodation that used to house over 1000 people (in the end, only 80 remained), and moved to a private room where a friend from his village allowed him to stay for free. By end of August he was sent on unpaid leave by the company, and boarded a plane to Egypt.

By December, flight routes were gradually being reopened for a winter tourist season, but still only two of the three terminals were in operation, and most former airport workers were still out of work. At the same time, more and more among those who had left the UAE during the spring or summer were returning to Dubai as long as their residence permits were still valid, hoping to find work.

But many migrant workers who returned home during the Covid spring and summer of 2020 were still at home, and didn’t know when and how to get back to their work sites in the Gulf.

We had breakfast and tea near the airport, and T. told us his news. “The situation in Egypt is economically very bad”, he said, “and it wracks people’s nerves.” Others in his extended family were looking for a way to leave, too. But many migrant workers who returned home during the Covid spring and summer of 2020 were still at home, and didn’t know when and how to get back to their work sites in the Gulf, either because they lacked the funds, or because they found the risk of returning without tangible prospects too grave. T. was lucky to have some modest assets that he could mobilise for the cost of the plane ticket, a PCR test, and a little cash for food and transportation. Importantly, he had the social capital of contacts in Dubai who might provide him information and help. Without those, he would not have come in the first place.

During the next days, as he began his search for work, he outlined his plan. Two years ago, he started building a new house at the outskirts of his village in Egypt, and he needs to work here in Dubai for two more years to see its construction to completion. Then he wants to settle down – but he doesn’t know what his plan will be after that. The prospect of a future after a definitive return is vague, even frightening, and he admitted that he had no idea how to make ends meet then. At the same time, he was affirmative that two more years would be enough of ghurba (living away from home) for him. He has worked altogether for nine years abroad, and he is in his late 30s. Soon, it will be enough for him.

His residence permit was going to expire in mid-February, and then a 30-days grace period would remain. That’s how long he had.

But first, he had to find work. His plan A was to be called back to duty by his company in case the operations at the airport picked up again. His plan B was to find work at another company, preferably at the airport, because it was the work he knew and liked best. His worst-case plan C was to collect his end-of-service payment from his employer, which would be just enough to pay his debts, and return to Egypt. His residence permit was going to expire in mid-February, and then a 30-days grace period would remain. That’s how long he had.

The city-state of Dubai, an emirate with far-reaching autonomy in the federal state of the UAE, has been a forerunner of neoliberalism in the Gulf, relying on speculative investment, trade, tourism, transportation, as well as all kinds of business practices enabled by the overall low level of regulation. (I have heard many allegations of Dubai being a money-laundering hub.) In short, Dubai thrives on openness, and is appreciated for that reason also by people I have met here. Egyptian and Filipino workers as well as Egyptian and Sudanese white-collar employees who have been my main contacts here, have all told me that Dubai invites one to live and spend one’s money here. The older stereotypes of Gulf countries assume a duality of nationals and migrants, where oil money is spent to hire engineers, teachers, and workers to provide infrastructures, education and services to a privileged minority of citizens. The UAE is an oil-rich country thanks to the large reserves of Abu Dhabi. But the emirate of Dubai ran out of oil already some time ago, and the little oil money it had was spent well to lay the foundations for a global trade hub. Today, a spectacle of consumer pluralism produced by migrants for other migrants is an important pillar of the city’s economy.

Egyptians whom I have met here repeatedly told me that working in Dubai both requires and produces a more cosmopolitan and sophisticated attitude than Kuwait or Saudi Arabia. Egyptians in Dubai regularly eat South Asian food, which Egyptians in other Gulf countries tend to avoid. An Egyptian who previously worked in Kuwait told me that he entered an Indian restaurant for the first time in Dubai. Dating and marriages between Egyptian men and Filipina women who meet at workplaces are common, enabled by the normality of mixed-gender sociality and, only since recently, also the legalisation of cohabitation of unmarried couples in most emirates of the UAE. Depictions of Gulf cosmopolitanism have tended to locate it at the higher income scales where contacts across different nationalities are more frequent and normalised, but it’s worth noting that also a few low-income workers find appeal in it.

Dubai’s lifestyle freedom comes with conditions, however.

Dubai’s lifestyle freedom comes with conditions, however. One of its flip sides is the complete absence of any political freedom. Months earlier, the UAE had normalised its relations with Israel, which was a highly controversial move in the Arab world. Practically nobody I met dared to express an opinion about it. Another flip side is the constant fear of contract cancellation and deportation. Migrants who can afford to have a family here are drawn to the well-ordered life in comfort and freedom, which they can maintain here much more easily than in Egypt, and yet they also acknowledge that “there is no stability here: you may have to leave anytime,” as an Egyptian born and raised in Sharjah put it to me.

The most tangible flip side that the jobseekers at time of Covid felt, however, was the uncertainty and precariousness of their prospective livelihoods – which is a general feature, in fact a productive condition of neoliberal economies that require individuals to work on themselves and their skills, take risks and seek for constantly new opportunities in the absence of safe and stable conditions to rely on and relax in.

In Part Two, T. finds a new job, but it makes him even more stressed and worried. Read it here.

All pictures by author