This is a story best told by images. Though it requires some words. Extended captions, if you will.

On Sunday, March 1, 2015, I attended a demonstration in support of Nadia Savchenko, a Ukrainian helicopter pilot who had been on a hunger strike in a Russian prison for nearly three months. Savchenko was days away from death. (She has since agreed to drink broth, after being denied her appeal for release in a Russian court on March 3, and having lost twenty-five kilograms.) Captured in eastern Ukraine by Russian separatists in June 2014, Savchenko was later accused of killing two Russian journalists during a mortar attack, spirited over the border from Ukraine into Russia, and incarcerated.

The demonstration took place outside the Russia Embassy in Berlin, a huge, fortified mansion on the formerly East German, now-posh tourist-central Unter den Linden Avenue. It was a small affair and infinitely sad. Around twenty people draped in Ukrainian and German flags sang songs in Ukrainian and flung the chant, in German, “Russia out of Ukraine!” in the direction of the impassive Russian Embassy. There was no sign that anyone was paying us the slightest attention. I imagined that, on the other side of the windows, our photographs were being taken for our FSB files and embassy employees were laughing at our futility.

After a few minutes, I had to leave. Unable to sing in Ukrainian and unwilling to shout in German, all I could do was stand there, crying and stroking my five-year-old daughter’s beautiful head. It reminded me of what I’d read about demonstrations during the Soviet period—a few brave souls shouting into the wind. The only difference was that we wouldn’t be arrested, just ignored.

Two days earlier, one of the main leaders of Russia’s opposition, a fearless man named Boris Nemtsov, had been murdered in Moscow. Four bullets in the back as he strolled outside the Kremlin. A driveby shooting. For anyone who has studied Soviet history, the parallels with the 1934 murder of Sergei Kirov were, at first, glaringly obvious. (Indeed, political scientist Karen Dawisha, who recently published a book on how Russian President Vladimir Putin has been robbing Russia, immediately wrote a piece on this topic for CNN.)

Two days earlier, one of the main leaders of Russia’s opposition, a fearless man named Boris Nemtsov, had been murdered in Moscow. Four bullets in the back as he strolled outside the Kremlin. A driveby shooting. For anyone who has studied Soviet history, the parallels with the 1934 murder of Sergei Kirov were, at first, glaringly obvious. (Indeed, political scientist Karen Dawisha, who recently published a book on how Russian President Vladimir Putin has been robbing Russia, immediately wrote a piece on this topic for CNN.)

In 1934, Kirov was Joseph Stalin’s right-hand man and the first secretary of the Communist Party in Leningrad. He was also charismatic and popular, Stalin’s main rival. Stalin handled the investigation into Kirov’s murder personally. Up to a million Soviet people died, accused of involvement in a plot to de-stabilize the USSR by killing Kirov. Years later it emerged that, in all likelihood, Stalin himself ordered Kirov’s assassination. Nemtsov’s death could provide similar grounds to Vladimir Putin to fabricate charges against anyone who dissents from the regime’s stance of extreme Russian nationalism and make sure that those people’s lives were cut short, in one way or another. In an eerie echo, Russian state media is accusing the US of killing Nemtsov in an effort to de-stabilize Russia.

At the same time, there are obvious ways in which the analogy doesn’t hold water. Kirov was a high-ranking Communist Party member and Stalin’s supporter. Nemtstov may have been slated to become President Boris Yeltsin’s successor in the 1990s, but had actively worked to oppose Russia’s police state since. In 1934, no one would have suspected Stalin of a political assassination. In 2015, accusations against Putin run rampant.

But there are also much larger differences between the two assassinations. In 1934, Stalin was just starting to cement his control over the USSR. The country’s outlying regions were coming, finally, under the centralized government’s rule. In 2015, Putin may be losing control over the Russian Federation, at least in the Far East, which is rapidly filling up with illegal Chinese immigrants. In fact, Russia may be at the end of existence as a state. The war with Ukraine, the nationalist fervor that has reached a fever pitch since the US imposed sanctions on Russia—these are masks to cover up what is happening on the ground.

I could introduce statistics–-the falling price of oil, a murder rate fives times higher than America’s, the lagging economy, the fact that Russian men’s life expectancy is the same as their age at retirement–-but I’d rather tell a couple stories.

While I was living in Kazakhstan, one of Russia’s former colonies, two years ago, I met a businessman who frequently flew to Moscow for work. He told me that on a recent plane trip, he had sat next to a man who managed a potato farm in Siberia. The man was at his wits end because the farm laborers he oversaw were too drunk too work. They drank from sunup until they passed out. The only time that they got out into the fields and broke a semi-sober sweat was when there were potatoes to be harvested, and turned into moonshine.

These days in Russia, there is an ever-increasing need to bribe doctors, teachers, and university professors. Medical treatment at public clinics and hospitals is officially free. But doctors earn miserably small salaries, just like police officers and university professors, who likewise seek to supplement their meager incomes with private donations. As one woman told me, if you have an operation and your family doesn’t make an appropriate gift to the surgeon, he might not sew you up all the way. Similarly, university students often have to buy good grades from their teachers. And if you can or must buy grades—not all teachers take bribes, of course—why study? Since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, this has come full circle.

Now, when you go to the doctor, as a Russian friend living in Berlin told me a few weeks ago, you hope the receptionist is kind and lets you know when the real doctor is receiving patients. Because all those students who bought their way into universities and paid for their degrees are now practicing medicine.

One more thing. Kirov was murdered by a single ne’er-do-well assassin named Nikolaev, either directly employed by the Soviet secret police or encouraged by them. (Apparently, Nikolaev was detained outside Kirov’s office while carrying a firearm and, subsequently, Kirov’s guard was removed, leaving the first secretary exposed.) Though there is no confirmation, Nemtsov was apparently murdered by Russian patriots. A few days before the assassination, according to a piece by Masha Lipman in the New Yorker, during a pro-Kremlin rally, one of the speakers said, addressing Putin, “Vladimir Vladimirovich, we are waiting for your order to get the traitors!” And on March 3, a group calling itself Novorossia claimed responsibility for Nemtsov’s death.

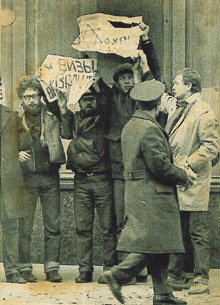

On March first, shortly before I attended the small demonstration outside the Russian Embassy in Berlin, people in Moscow and St. Petersburg and elsewhere marched to commemorate their fallen hero. In a city where any “traitor” can be shot for speaking out against Putin, some fifty thousand people risked their lives. These images illustrate better than any scholarly argument exactly how 2015 isn’t 1934.