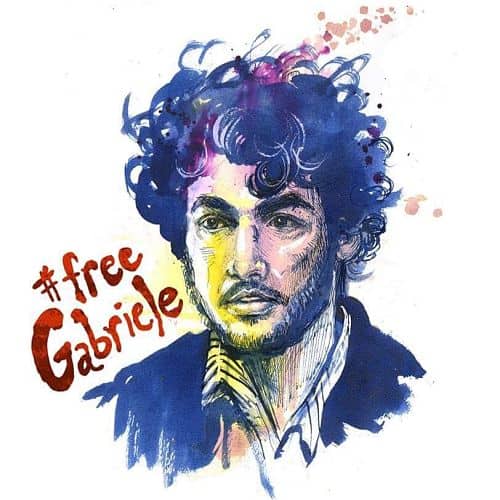

Gabriele del Grande is a journalist and human rights activist, co-director of the documentary ‘On the Bride’s Side’ and founder of the blog Fortress Europe. He is now doing research for his new book ‘A Partisan Told Me’, rethinking the Syrian war from the people’s perspective.

After being detained on April 9th in the city of Reyhanli, Gabriele del Grande, was put into isolation in a removal center of the Hatay province of Turkey. During his 15 days he was held without charges and started a hunger strike. Fortunately today, Monday 24th, he has been released at 7.35am.

Dr. Alexandra D’Onofrio, Gabriele’s partner and fellow anthropologist, agreed to tell us her experience of these confusing and tense days, while Gabriele was held in the removal center.

Paloma: Can you tell me about Gabriele’s research?

Alexandra: Gabriele has been working on his new project ‘A Partisan Told Me’, for which we realized the video for the crowdfunding together in Athens before he left. 1342 contributors, he calls ‘grassroots publishers’, participated in the campaign, encouraging him to do this research. His idea was to travel to Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Tunisia and Libya, working with memory to re-tell the story of the Syrian war from its beginning, from the uprising in 2011 until now, following all the different phases and the rise of ISIS.

The intention was to talk about the complex dynamics going on, not only from the perspective of geopolitical analysis, but primarily from the human point of view of the protagonists’ stories.

Those people who were on the street from the very beginning, or who ended up taking arms, at a certain point, to then change factions once again; the story of families who have brothers fighting on opposing sides. Gabriele was trying to reflect the complexity of the war, understanding that whatever side one takes there are no winners. It is difficult, because he doesn’t take sides, so many people are unhappy with that because he is not openly saying he is pro one side or the other. Of course, he was pro-pacifist and the activists who took the streets initially were his main contacts at the very beginning. But then the war complicated everything, and most of them are not in Syria, they are out, they are the defeated.

‘The book I have in mind will tell the story of the war in Syria and the birth of the Islamic State through a great project of narrative journalism which weaves the epic stories of the common people into the history of the last twenty years of war and terrorism. Because Isis is talked about every day, but very few people have really understood what it is all about. Who are the men and the women who in their thousands have joined to defend the Caliphate? Who are the civilians who stayed behind in their towns? But above all: how did we get here?’ Gabriele del Grande

Gabriele del Grande explaining his research about the Syrian war:

What happened when the Turkish Police arrested him?

Apparently, when they got him, he was eating in a restaurant while talking with a Syrian informant. They were in Reyhanli a city near the border with Syria, but he had no intention of crossing the border. Border areas are always interesting locations for listening and collecting the stories of fugitives. Eight policemen approached them in the restaurant and started asking about what he was doing and his job. Probably he told them they were just talking, but they didn’t believe he was a journalist because he had no camera and they took him in. Initially they told him they were just going to check and he would be deported soon. The problem is that all this is unofficial, nobody has told us anything official. There is no official written declaration onto white paper saying Gabriele del Grande was stopped and detained for this reason. They have been telling us he was stopped in an area where he shouldn’t have been without permission, because it is a movement-restricted area and there is a lot of attention, especially under the referendum. But the job of a journalist is often to be in places where “a witness” shouldn’t be. So they took him, checked him and they said they would expel him the next day.

Initially, what we know is that he was supposed to be sent back Thursday 13th, when he had a flight back to Athens. However, that same day, instead of sending him to the airport, they took him to another removal center, where he was put into isolation. The previous center in Hatay, being near the border, was full of Syrians. The Turkish Authorities who saw him do his normal thing, ‘talking to people’ in Arabic, didn’t know what was going on and probably became suspicious. When the Italian honorary consul went to the detention centre in Hatay on Friday 14th April he was refused permission to see or talk to Gabriele directly. The director of the centre told us that he was interviewing people and that his behaviour represented a threat to security, so they decided to move him, without telling the Italian authorities, and us as a consequence, where he had been transferred.

The Italian honorary consul was told that Gabriele didn’t want to talk to the authorities. Later, we found that this was not true at all. He had actually written down on a paper that they made him sign that he wanted to see the consul. So as they restrained his right to call or see the lawyer and the consul, last Tuesday 18th he smashed his cell and forced the door in protest in order to get a call. Finally, they allowed him to call us, and that’s when we found out where he was locked up, that he had asked to see the authorities and a lawyer, that he was in isolation and that they were interrogating him about his work. As he was not under arrest, we have no idea who interrogated him.

In the interrogatories he has given general replies but refused to give any detailed information without the presence of a lawyer. Later, when they found out he was actually a quite famous journalist, as the news of his detention passed on the CNN, they were very excited about it, wanting to do selfies with him. He was joking about it, when he called me. At least there is a nice atmosphere inside, although it is like a prison. The problem is being detained without information, without legal assistance, without knowing what is going to happen, how long are you going to be in and even being interrogated without a lawyer.

If Gabriele had been officially arrested he would have had right to a lawyer almost immediately, but these are removal centers – detainees are there in order to be expelled, so there is no reason to isolate somebody and detain him for a number of days, without removing this person. Taner Kilic, our Turkish lawyer, says it is completely illogical to the place and to the process of removal what is happening to Gabriele and that it is illegal.

Now we are in a very special Turkey, there was the referendum but also the country is under a state of emergency laws, so understanding what is happening, how long it can last and what rules there are, is very complicated.

Do you have a theory about what happened?

People have been saying many things. Some say they were following him and they just waited for him to be in the right spot, catch him, put him in a place where rights would be suspended, so that they could find out a bit more. I am not sure that this is completely true. These were particular days where the attention was particularly focused on people talking to each other. Maybe there were just following him without knowing if he was a journalist or not, and caught him because they found his movements suspicious. Maybe they didn’t realize what he was doing exactly, but slowly found out what type of job he was doing and wanted to use him in order to get information he had. Maybe this is a lesson the Turkish Authorities are trying to give to other journalists researching this kind of sensitive issues. It is very complex and there is a bureaucratic issue as well. Bureaucracy takes lot of time in Turkey, so it is not necessarily a complot. We are all confused about why they are kept him so long. Is it just because of the bureaucratic reasons? And if he was just waiting for expulsion, why didn’t they give us his file? They did not give the lawyer the file on Friday 21st when he asked for it. The thing is that they probably don’t want to tell us he was set for expulsion because they want to keep investigating about his work in case they find out from him some useful information. This information might then also put him in a position of being charged legally.

So what is so suspicious from Gabriele’s work, can you tell me some anecdotes he told you about his research these past months?

He would come back with so many of these anecdotes. Anecdotes of survival strategies in Syrian prisons, stories of love, jokes of men, because it is mainly a male situation where he manages to do his interviews. It is a male storytelling context. That gives you the idea of how he interviews people, which can be said to be very anthropological. Even through he might sit down with a recorder, the conversation he has with his informants is usually very informal and it develops in a flow. Because he can pick up all the nuances in the language, conversations would flow from political to religious, from the scriptures to the news, or from jokes to talking about parenthood. So because he knew it was ambitious for him alone to reflect on all the complexity of what Syria has turned into and talk about the war through the human stories of the people that got involved in it, he felt propelled to study a lot. He has been collecting material which has been inspirational to Islamic militants, videos, books. He was learning the Koran, every morning he would recite Suras to remember, and understand how people really got motivated in Islamic activism. It is not only about major power sources, money and arms coming from everywhere, but it is also a story of oppression.

If you have been oppressed for decades and decades, both by neoliberal states as a religious activist – like it happened to the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt-, Islam and redemption are the few sources of hope that are left.

Redemption, in the sense of taking over, is a way for the militants to say they believe in an alternative to individualism, consumerism and that they want to to be in charge of their “own” land, redefying values and ideals according to a re-interpretation of tradition. However many militants also understood that the war has turned people into beasts, hence they abandoned the arms or their position within the organization and fled to other states.

At the same time, Gabriele would come back saying there is something very interesting about war, people get really addicted to it and they miss it after. War is also a drive for life even if you are going to die, but it gives you a purpose that you are doing something. In a way, war is part of the story of Islam and how it came in to being according to the religious scriptures.

To conclude, can you tell me something about how you felt these days?

I always thought this could happen. He is that kind of person that is aware of the risks, but feels the urge to be where he needs to be as a journalist, to tell the story of this historical moment. He started going to Syria when we found out we were expecting our first child. Before, he was in Libya and that was quite troubling, because it was during the war and the shelling. It was difficult, but I have trusted him all along; I have trusted the fact that he is an incredibly clever man who has his antennas ready. He not only speaks with people, but he also doesn’t call too much attention, he goes really embedded, as they say. He can pass as an Arab and is often hosted by his friends that are locals, so it is very rare that he takes the distances of conventional journalism and yet his work is widely recognised both in Italy and internationally. He is always open and honest about his work as a journalist wherever he goes, but it is the way that he carries out his research that keeps him safe too, and that has made me trust him and appreciate the necessary work he produces. Of course, I would like to talk to him about this time and understand whether he expected this or not. Especially since he wasn’t working on sensitive topics in Turkey, like the Kurdish issue for example. When he left I was normal, like every time, and I knew where he was going to be. I knew he was in Reyhanli to interview Syrians waiting to go back in and had no intention of actually crossing the border, as some people suggest. He was there because that’s where many Syrians with very interesting stories are right now, populating the border waiting to get back to their country.

On a final note, I’m sure he will have made the maximum of out of this experience. He will be soon writing stories about these places he has been and that we all have been imagining. He is probably going to come back stronger than what he was.

Even though he is expected to be menaced or feel threatened, he is going to come back with more stuff to tell and a greater urge to tell things, nothing like this can stop him. So the decision is left to us, we either go with him or we are left behind. I would say that it is better for the rest of us to take the ride, otherwise we will be losing out from it. After these days of anxiety, let’s see him back and we will see on which adventure he’ll take us next.