Infrastructure is, in common understanding, a very material thing. We think of it as something made of iron and concrete. Even when going unnoticed in our everyday lives, infrastructure is an intimate presence in the working – or non-working – of much of what we deal with on a daily basis. Think of the roads we walk on our way to work in the morning. Or the server farms that store our data. Or the “cloud” in which different drafts of this article are located. Infrastructure, social scientists tell us, is both visible and invisible. Social and technical. Political and poetical.

As such infrastructure is also both material and immaterial. It is as concrete as the piece of railway that carries the subway cart I’m sitting in, and as imaginative as NASA’s plans for a permanent station on Mars. Both, however, whether they exist or not, produce tangible outcomes. To better understand this set of apparent contradictions, social scientists have generally thought of infrastructures as relational. That is, it resembles more a dynamic socio-material assemblage, rather than merely a durable technical system (cf. Anand, Gupta and Appel 2018; Harvey, Jensen and Morita 2018; Rippa, Murton and Rest 2020).

This future – currently highly immaterial – issue of Roadsides is concerned with one particular relational aspect of infrastructure that has been scarcely explored so far. That between infrastructure and archive.

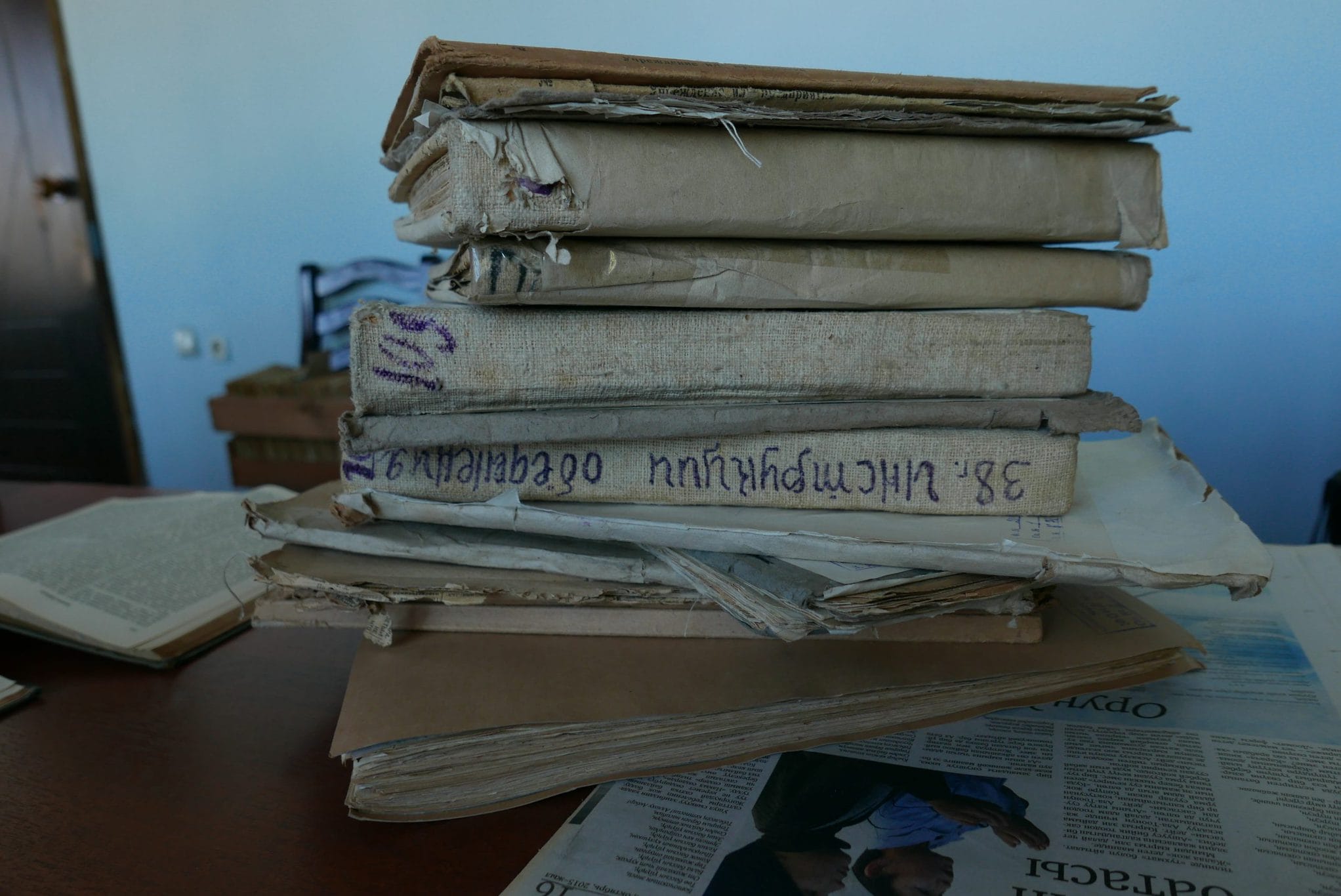

The point of departure for this issue is that the history of infrastructure that now shapes our lives, as well as of infrastructure that has never been built, lies in particular bodies of texts — documents, pictures, letters, books, videos, and so on.

These archives are central to the imagining of infrastructure, to their planning as well to their making. Yet the relation between concrete infrastructure and such bodies of text are seldom addressed.

As pertains to humanities scholarship traditionally speaking, archives have typically been state-run institutions holding historical, political, economic and social records from across various arms of governance and societal order. For the purpose of this issue, however, archives are understood in the broadest sense: any collection of documents, stories, reports, notices, banners, photographs, video recordings, sounds, posted bills and rumours – anything textual (in the term’s broadest sense) that represents a writing and a reading of the social worlds created and mediated by infrastructure. Following on the work of Barry (2013), which enlists an analysis of official public oil industry documents to reveal their performative and institutional politics, we understand archives as consisting of both formal/official and local/vernacular material production, so as to show the multiple discourses and representations implicit in infrastructural processes.

In this sense, the archive is an epistemic assemblage that can be understood in three ways:

a) an amalgamation of projective and managerial devices; b) a testament to calls for accountability and transparency made by local and international investors, municipalities, financial institutions and civil society organisations (Barry 2013); and c) a space for the reflection on infrastructure’s quotidian nature: the lived experience of their planning, construction and maintenance.

This understanding of archives is foregrounded by the work of several scholars that, particularly within anthropology, have recently troubled commonsensical understandings of the archive as a written and solid past (Stoler 2002; Mueggler 2011). Rather, this scholarship addresses archives — and archival research — not merely as sites of knowledge retrieval and extractive activity, but as a site of engaged critical ethnographic research. As Ann Stoler succinctly puts it, scholars need to move “from archive-as- source to archive-as-subject” (2012: 93).

In bringing together these two approaches, one based on the recent “infrastructure turn” in the social science and one rooted in a critical approach to archives and archival knowledge, this upcoming issue of Roadsides will thus address some of the following themes:

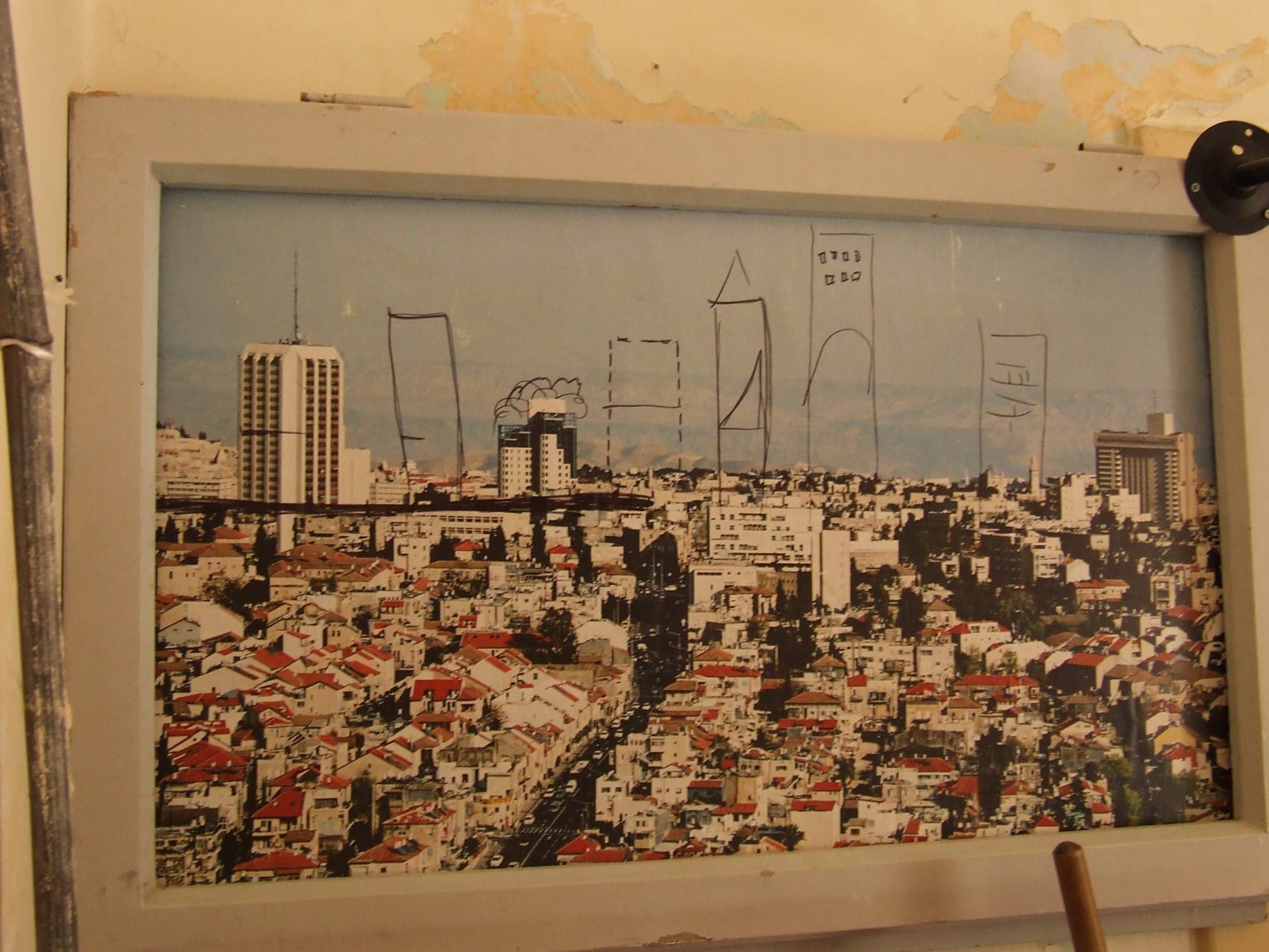

- Infrastructure and the politics of imagination. How are infrastructure projects envisioned and documented, before, during, and after their construction?

- Infrastructure projects that exist only within particular archives. What does the history of what has not been built — or what Carse and Kneas (2019) term the “shadow history” heuristic — tell us about what has been built?

- The archive as an infrastructure. What can we gain by applying some of the infrastructural thinking outlined above to archives and archival research (and vice-versa)?

- Methods. The study of infrastructure often presents inevitable methodological issues. How does an archival approach can help and how might that look like concretely?

This collection is scheduled for publication in February 2021. For any queries, or submissions, please email Alessandro Rippa at alessandro.rippa@tlu.ee. If you want to receive the Call for Papers and updates on Roadsides publications and future issues, please subscribe to our newsletter. To peruse all issues of Roadsides, visit the journal’s website: https://roadsides.net

References

Anand, Nikhil; Gupta, Akhil; and Hannah Appel (eds.). 2018. The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Barry, Andrew. 2013. Material Politics: Disputes along the Pipeline. Malden and Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Carse, Ashley and David Kneas. 2019. “Unbuilt and Unfinished: The Temporalities of Infrastructure.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 10: 9-28.

Harvey, Penny, Jensen, Casper Bruun, Morita, Atsuro (eds.). 2017. Infrastructure and Social Complexity: A Companion. London and New York: Routledge.

Mueggler, Erik. 2011. The Paper Road: Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rippa, Alessandro; Murton, Galen; and Matthäus Rest. 2020. “Building Highland Asia in the 21st Century.” Verge: Studies in Global Asias (forthcoming).

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2002. “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance.” Archival Science 2: 87-109.