After South Sudan declared its independence from the Republic of the Sudan in 2011, one could read in the international media scene: “South Sudan fights to implement Rule of Law […] At the heart of this new battle are approximately 250 lawyers [which] have come back from abroad.” (Voice of America 2013) However, at the heart of the ‘rule of law’ battle there are rather international actors with their virtual toolboxes, as will be shown.

All over the world one can observe – in the name of ‘rule law’ (RoL) – immense international interventions taking place, predominantly in so called ‘war-torn’ or ‘post-conflict’ countries such as South Sudan. Agreeing with Christopher May (2014), RoL seems to have become “the dominant paradigm for state governance in the international arena”. The UN Declaration on the Rule of Law at the National and International Levels adopted by the General Assembly (2012) reaffirmed: “We are convinced that good governance at the international level is fundamental for strengthening the rule of law.”

By claiming that RoL represents a global consensus towards ‘problems’ of governance, influential intergovernmental institutions have urged countries to undertake legal reforms in order to implement it. Moreover, increasingly private companies and law firms are sprouting up everywhere. Their ‘experts’ circulate around the world and carry with them manifold peace-making, constitutions-making and institution-making models and toolkits of how to implement RoL. Nowadays, almost all intergovernmental organisations have specialised branches for promoting it. Accordingly, on the website of the UNDP branch for South Sudan it reads, “rule of law is essential for security, economic growth and the provision of social services in South Sudan. It provides mechanisms for peaceful resolutions of conflicts, the certainty that allows the private sector to develop and flourish, and the access to justice that ensures respect for the human rights of every individual, including women and marginalized groups”. (UNDP)

The very vague term ‘rule of law’ is actually a locus of diverse, and sometimes contradictory claims tackling ideas of ‘universalism’ and ‘diversity’ alike. Nevertheless, ‘rule of law programmes’ have become a vehicle through which specific notions of law are promoted, partly imposed by dominant international actors. Particularly, in light of the often heavily relying of ‘post-conflict’ settings on international funding, RoL has become a layer of conditionality. Agreeing with Migdal and Schlichte (2005: 33):

There is always something for international actors to fix, always a plan that the international community should contribute something to, and always something that goes wrong and needs fixing through further intervention and programs. Global discourses on development, democratization, human rights, peace and more have become the code for institutionalized involvement of all kinds of externally-rooted agencies that shape states on all continents.

The “establishment of RoL qua grundnorm” seems to be cultivated through a “professionalization of global politics, and the deployments of programmes of technical assistance that have sought to socialise elites and legislators into the RoL mind-set [and] the increasing pre-commitment to RoL seems to be sustained by political self-maintenance of the legal profession”. (May 2014) Thus, multiple ‘experts’ promote their tool (law) as a solution to ‘problems’ of order. The experts’ RoL promotion tends to focus on broad categories: legal and constitutional and on institutional reform.

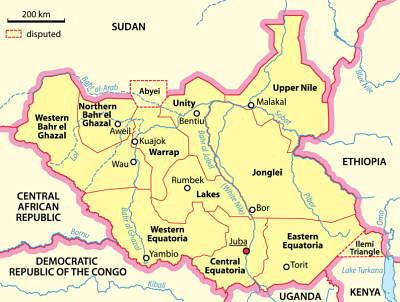

Competing RoL actors in the international arena are eager to find their ‘niche’ for ‘supporting’ post-war countries such as South Sudan in its ‘transition’ to a ‘modern’ democratic state. RoL promotion still assumes the existence of the ‘modern’ (nation)state. The idea of the ‘modern‘ or ‘territorial state‘ belongs to “a fundamental ontology of political thought” (Schlichte 2004), which was characterized by the legal philosopher G. Jellinek‘s in 1900 by three elements of statehood: territoriality, sovereignty and ‘nation’. It has become the only valid state order system (Eckert 2011). The idea of the state was attributed with different meanings, but the notions of territoriality (borders), internal and external sovereignty and the state as a body of administrative institutions seem to prevail (Schlichte 2004). For instance, the presumption of state’s monopoly on the use of force does not take into account that in most states there are multiple structures of law and authority that (co-)exist interdependently with ‘the state’.

Competing RoL actors in the international arena are eager to find their ‘niche’ for ‘supporting’ post-war countries such as South Sudan in its ‘transition’ to a ‘modern’ democratic state. RoL promotion still assumes the existence of the ‘modern’ (nation)state. The idea of the ‘modern‘ or ‘territorial state‘ belongs to “a fundamental ontology of political thought” (Schlichte 2004), which was characterized by the legal philosopher G. Jellinek‘s in 1900 by three elements of statehood: territoriality, sovereignty and ‘nation’. It has become the only valid state order system (Eckert 2011). The idea of the state was attributed with different meanings, but the notions of territoriality (borders), internal and external sovereignty and the state as a body of administrative institutions seem to prevail (Schlichte 2004). For instance, the presumption of state’s monopoly on the use of force does not take into account that in most states there are multiple structures of law and authority that (co-)exist interdependently with ‘the state’.

The myth of the existence of a ‘territorial state’ becomes particularly obvious in post-conflict settings since its constitutive elements (at least partly) do not exist (Seidel 2015). Underlying state-centric assumptions often lead to top-down rule-of-law efforts on state institutions and state legal systems whose impacts appeared to be rather doubtful. This ‘problem’ of implementation or the gap between ideas and practice has led to a certain self-reflexivity within the ‘international actors’ scene. The 2004 UN Report on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post Conflict states:

The international community has not always provided rule of law assistance that is appropriate to the country context. Too often, the emphasis has been on foreign experts, foreign models and foreign-conceived solutions to the detriment of durable improvements and sustainable capacity […] We must learn better how to respect and support local ownership, local leadership and a local constituency for reform.

Accordingly, during the last few years a slight shift in the international conceptualisation of RoL can be observed: “some serious consideration [has been taken] to legal pluralism” (Grenfell 2013), taking into account that legal pluralism is a ‘universal feature of social organisation. Many political and legal academics identify RoL as essential to justice-keeping polity. It is also believed to be a precondition for establishing principles such as human rights and democracy. (see Rajagopal 2008) Nevertheless, the idea of ‘natural justice’ seems to be still inherent within most of RoL narratives.

One of the cornerstones of the ‘rule of law’ promotion is the diffusion of specific schemes of constitutionalism. It is expected to show long-term commitment to reform and non-violent conflict resolution mechanisms. Constitutions, when interlinked with International law, allows international (human rights) actors to become immediately part of domestic law. Thereby, “[t]he discourse of constitution-making now commonly employs terminology of ‘stakeholders’, ‘clients’, and ‘best practices’, suggesting that the relationship between citizens and states can benefit from a market of expert knowledge” (Kendall 2013). The extensive assistance of international actors in ‘post-war’ settings such as South Sudan has become part of peace-making efforts. Thereby, constitution-making has become a common normative tool within the context of the broader concept of rule of law framework.

On South Sudan’s declaration of independence day, President Salva Kiir Mayardit presented to the crowd an oversized red ‘book’: the Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan [i] (TCRSS). It was evident the text had been thrown together quickly without the participation of many local societal actors and authorities, and without addressing critiques such as the imbalance between members of political parties and civil society. The making of the TCRSS shows the dominance of the some powerful actors of the ruling People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) party who sought to assure that their ideas and interests would find their way into the “supreme law of the land” (Art. 3(1) TCRSS). These ideas of a strong ‘centre’ are reflected, for instance, in the excessive powers of the South Sudanese president (e.g. Art. 101 r,s TCRSS).

South Sudan’s current ‘permanent’ constitution making [ii] is supported as well by international actors with a virtual toolbox of models and templates. The support is provided primarily to governmental actors in the form of technical and legal ‘expertise’ of ‘experts’ ranging from individual activists and academics, individual and groupings of states, (supra-)regional institutions, non-local NGOs, commercial enterprises, research institutions and think tanks.

Nevertheless, national actors are caught between competing international actors and often find themselves in a dilemma of how to manage the ‘well-meaning offers’.

Offered services come with legal ‘benchmarks’, international ‘best practices’ and conflict-resolution mechanisms and they are almost always interwoven with political and economic interests. One may ask whether these interventions threaten the idea that the constitution “derives its authority from the will of the people” as stipulated in the Transitional Constitution (Art. 3(1)) and as demanded by many local actors.

Even though there are no comprehensive blueprints, we have to bear in mind that constitution making in ‘post-war’ settings is usually made under huge political and time pressure and directly attached to ‘state-building’ efforts. Actors are therefore not only prone to apply model constitutional frameworks but also create “procedural objectivities” through supporting guidelines and templates; whereby “superficially neutral, elementary procedures are introduced, which are supposed to correspond to an unproblematic reality of facts and data”. (Rottenburg 2009)

Even though there are no comprehensive blueprints, we have to bear in mind that constitution making in ‘post-war’ settings is usually made under huge political and time pressure and directly attached to ‘state-building’ efforts. Actors are therefore not only prone to apply model constitutional frameworks but also create “procedural objectivities” through supporting guidelines and templates; whereby “superficially neutral, elementary procedures are introduced, which are supposed to correspond to an unproblematic reality of facts and data”. (Rottenburg 2009)

These guidelines reflect international policy discourses on ‘ownership’, expecting the common people to participate and to have their say on constitutional frameworks. The concept of ‘ownership’ has emerged as a lesson learned in the general debate on what is known as ‘aid’ or ‘development’ assistance. (Sannerholm 2012) A paternalistic attitude of international actors appears to be continued in a new guise. Now, international agencies ‘consult’, ‘listen to’, ‘include’, and ‘provide for’ ownership for local actors.

Based on guidelines and handbooks, action and activity plans are provided to governmental actors. Activities on how to produce a constitution are timely sequenced. Project management terminologies such as ‘consult’, ‘create’, ‘produce’ and ‘organize’ reflect a rather linear process. These kinds of plans have ingrained the international concepts of ‘ownership’. ‘Responsible actors’ (locals) and ‘implementing actors’ (internationals) are defined. The practice shows that activities relating to ‘expertise’, ‘research and ‘know-how’ are constructed conversely.

This raises the question of who actually ‘owns’ the process?

Regarding ‘popular ownership’ the pre-modelled activity plan for South Sudanese constitution-making is comprised of certain components such as ‘civic education’ and ‘public consultation’ for the South Sudanese people in all regions. Thus, does the ‘public ownership’ tools go beyond a simple awareness campaign on the constitution-making made by the national and international elites? Another dilemma becomes obvious: how to deal with ideas of ‘popular ownership’ while following the convincing logic of the objectived procedures? The timetable of constitution-making seems not to be very flexible for the embedding and re-evaluation of ideas, which might arise during the public consultation process.

Let me conclude by emphasising that the ‘assisted’ constitution-making process takes place in a highly segmented South Sudan where violent and non-violent negotiations on the mode of statehood are still on-going. Numerous issues written in a constitution are opposed by a multitude of actors with different claims. In light of the absence of a ‘nation’ a predetermination of national ideas in the ‘supreme law of the land’ seems to be questionable.

Even though the modes of statehood are still under negotiation, the ‘rule of law’ toolsets (provided by international actors) regulate the constitution-making process in a way that may reduce the chances of integrating ideas from different parts of the segmented society while proclaiming the idea of ‘popular ownership’.

The question arises whether those ‘rule of law’- tools become rather an obstacle in the quest for ‘legal certainty’, ‘stability’ and ‘peace’. (see Seidel/Sureau, forthcoming) Recognizing some of the claims while legally regulating disputes through legal provisions can impede ongoing negotiation processes and may rather intensify than solve conflict dynamics.

Footnotes

[i] The TCRSS is based on the Interim National Constitution, 2005 whose substance was mainly predetermined through the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. [see Dann, P. and Z. Al-Ali (2006)]

[ii] The ‚permanent‘ Constitution-making is intended to be completed by 2015. In light of the current political dynamics in South Sudan it seems to be rather unlikely that the deadline will be kept.

References

Ki-moon, Ban (2013) Building a Better Future for All: selected speeches of United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon 2007-2012, United Nations.

Behrends, A. et al. (2014) Travelling Models in African Conflict Management. Translating Technologies of Social Ordering, Brill.

Dann, P. and Z. Al-Ali. (2006) ‚”The Internationalized Pouvoir Constituant: Constitution-Making under external influence in Iraq, Sudan and East Timor”, Max Planck UNYB 10.

Eckert, A. (2011) “Nation, Staat und Ethnizität in Afrika im 20. Jahrhundert”, in Sonderegger, A. et al. (eds.) Afrika im 20. Jahrhundert. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Promedia.

Grenfell, L. (2013) Promoting the Rule of Law in Post-Conflict States. Cambridge.

Humphreys, S. (2010) Theatre of the Rule of Law. Transnational legal interventions on theory and practice, Cambridge

Kendall, S. (2013) ‚”Constitutional Technicity: Displacing politics through expert knowledge”, Law, Culture and the Humanities.

May, C. (2014) The Rule of Law. The common sense of global politics, Elgar.

Migdal, J.S. and K. Schlichte (2005). “Rethinking the State”, in Schlichte (ed.) Dynamics of States: The Formation and Crises of State Domination, Ashgate.

Rajagopal, B. (2008) “Invoking Rule of Law in Post-Conflict Rebuilding: A critical Examination”, William and Mary Law Review, 49.

Rottenburg, R. (2009) Far-Fetched Facts: a parable of development aid, Cambridge.

Sannerholm, R.Z. (2012) Rule of Law after War and Crisis: ideologies, Norms and methods, Intersentia

Schlichte, K. (2004) “Staatlichkeit als Ideologie: Zur politischen Soziologie der Weltgesellschaft – Statehood as Ideology: Political Sociology of World Society”, in K.-G. Giesen (ed.) Ideologien in der Weltpolitik, VS.

Seidel, K. “When the State is Forced to Deal with Local Law: Approaches of and Challenges for State Actors in Emerging South Sudan”, in: Hoehne, M.V. and O. Zenker (eds.) Processing the Paradox: When the State has to Deal with Customary Law, Ashgate. (forthcoming)

Seidel, K. and T. Sureau “Peace and constitution-making in emerging South Sudan: on, off, and beyond the negotiation table”, in Seidel and Sureau (eds.) Emerging South Sudan. Negotiation Staathood. (forthcoming)

Government of South Sudan (2011) The Transitional Constitution of the Republic South Sudan

United Nations. 2012. Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Rule of Law at the National and International Levels, UN Doc. A/RES/67/1.

United Nations. 2004. Report on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post Conflict states, UN Doc S/2004/616.

Voice of America, 5 November 2013

UNDP: Rule of Law