Most objects in our households have a purpose. They clothe, seat, feed or transport us. Some object do extra duty; they communicate something about us that we want to say: that we are wealthy, or on-trend, or knowledgeable in a certain field. You can learn a lot about someone by looking at their objects.

Anthropologists have long experience studying objects. They can pick up a spearhead, or a piece of broken bowl, and tell you a lot about the people who used it: when they lived, what they ate, who they traded with, how they lived, and even some of the things they believed about the world. When the people themselves are no longer here, their objects can still speak for them.

Indeed, it is amazing what objects can say.

As gifts, they can prove we are generous – and how highly we value the recipient. As commodities, they can drive economies, mobilising labor and organisations to produce and distribute them. The anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has described objects as having social lives. Life revolves around them – and objects join in. This dress, bought vintage with the beads running round the edges, may have seen more parties than I have.

Some objects, indeed, seem to develop a social presence: something far out of proportion to their size or usefulness. As an example, I once met a teapot with a broken spout. It was made of squat brown glazed clay and sat high on a shelf in the office of a colleague. The community development manual on the desk in front of me had a sketch of a teapot on the cover, as did my colleague’s letterhead. Same teapot.

It was, I learned, an important teapot. That particularly pot had travelled the district to rural community development meetings for over a decade. It had sat on kitchen tables brewing the tea while women sat around it and talked. The topics changed, the tables changed, but the pot was always there. It was such a central pot that it had become the emblem of the Centre, and of a whole methodology for rural community development work.

In one of countless journeys from car to table, the pot had fallen, and it was no longer used to serve tea. Now it sat amid annual reports and scholarly books in an office full of busy coffee-drinkers: an illogical object, but one with a great deal to say.

Doll Scraps and Unshuttable Cupboards

The teapot was, of course, a one-off: one teapot (now unique thanks to its tumble) that meant something to one particular group of people, who no longer drink tea, but remember when they did. The world is full of objects like that teapot: from lucky socks, to the crown jewels. For someone – whether a person, a group, or a nation – the object means more than it would appear on the surface.

English and Australians enter annually into cricket combat for a small heap of wood ash encased in a trophy cup. Traditional Andeans keep old textiles safe as the most prized community possessions, a woven local history. The Olympic torch is passed from hand to hand, regardless of any requirement for light.

Such objects clearly have a social presence: they signify something more than themselves. Like flags or national treasures, they are often a complex mix of history and symbols: of what-we-were and of what-we-aspire-to-be.

The first car is often hard to sell; the first doll, in rags and tatters, is boxed and stored but never thrown away. And for some of us, its gets worse: the clothes of the person we loved – cupboards full, untouched; the books we might need to speak with again, following us from country to country, heavy and unread; the cupboards overflowing with objects that have had lives and, having lived, cannot be summarily disposed of by any ordinary means.

I have a great admiration for those people who make a business of clearing other people’s clutter. Clutter is the term that most use: an interesting choice. The word names up the unnecessary and unwanted, with overtones of lightness and insubstantiality: clutter, unlike mess, is easily removed.

While I suspect most households have a certain amount of clutter, it is dangerous to assume that our cupboards are necessarily filled with insignificant, lightweight objects. I wonder, for instance, how a decluttering professional would manage in the West Virginia closets of my aunt:

‘Don’t go in there, that’s all the kids’ stuff.’ (The youngest child of the house is fifty).

‘No, don’t open that box, that was my mother’s.’

‘No, leave that, we need to hold onto that.’

I wonder how often those who wish to de-clutter come face-to-face with socially alive objects. Few of these objects have lived long enough to become family heirlooms, let alone national treasures. Yet they have been amid people’s lives long enough to resist easy disposal. It is illogical to keep them, they just take up space; but they mean something that cannot be easily discarded.

In poor countries, where there are fewer objects, these objects are easily seen: pinned to an adobe wall, hung over a nail, tucked onto a shelf for safe-keeping. In wealthy countries, we need cupboards to house them, attics, even storage rooms. An enterprising stranger might well call these objects clutter, but up close, they have weight. To de-clutter, such illogical objects must be intentionally killed off – yes, get rid of that old thing! – severed from their meanings with pure cold rationality. Or, if that is distasteful, a paid professional can quietly make them disappear.

Of course, there is still a problem. The object goes, but the meaning stays. Months, even years later, someone will inevitably ask: Whatever happened to that? They look for the missing object, and they feel bereft. Something has been lost.

Yardsticks and Footy Scarves

Some objects, then, have a particular meaning for particular people. This meaning may be shared within a household, family, or a community, but not further afield – one person’s treasures are, to invert the saying, another’s trash. The teddy bear face down in a puddle quickly turns to nothing but litter.

Socially alive objects are only alive to whom they matter.

But there is another category of objects that are, at one level, less ‘significant’, and at another level, much more so. These are the objects that we keep around for no obvious practical or personal reason. They are not useful objects, nor are they objects that we imbue with value through our particular shared history together. Rather, they are objects that we simply have: in household after household, without much attention or notice, but consistently, without question. These are the illogical objects that we take for granted.

Practically every household, for instance, has a television. At one level televisions are eminently practical objects: they provide on-tap news and entertainment, and they enable people to feel socially connected by ensuring that they have shared topics to discuss with friends and colleagues. Of course, for the same reasons, televisions are highly illogical: they provide social connectivity by encouraging people to stay alone in their houses.

What sorts of illogical objects do we keep in our households? When I was growing up in the United States in the 1980s, we had yardsticks. For those unfamiliar with the concept, a yardstick is a piece of wood, rather like a ruler, but three times as long: measuring exactly one yard. A yardstick is intended as a measuring device. Nevertheless, it is too long and unwieldy to measure anything small, and too short and inflexible to measure anything large.

The yardstick is the classic illogical object: useless for measuring, yet every household had one – at least one.

It would have been odd not to. When I arrived in Australia and needed to fetch a fallen object from behind the fridge, I asked my Australian husband to hand me a yardstick.

‘What’s that?’ he asked.

Like iced tea and canned pie filling – both eminently practical objects from my childhood in the States – I could not conceive that yardsticks were simply not here. In the past decade, both the iced tea and the pie filling have found their way to Australia, but the yardstick (or its metric equivalent) has not. And why should it? Despite its omnipresence in the kitchens and utility rooms of my childhood, it was an object that never did what it was designed to do.

So how did the yardstick infiltrate American homes? Quite simply, yardsticks were free. Next to ballpoint pens and photo calendars, they were the most popular promotional object distributed by local enterprises. Yardsticks were free; in the words of the capitalists, they could be obtained for zero outlay. Not only that: they looked practical. They were measuring devices. So, unlike other free things, they stayed. The yardstick came to stay in households across America because it met a need – not for measuring, but for having the capacity to measure, the appearance of the well-measured household.

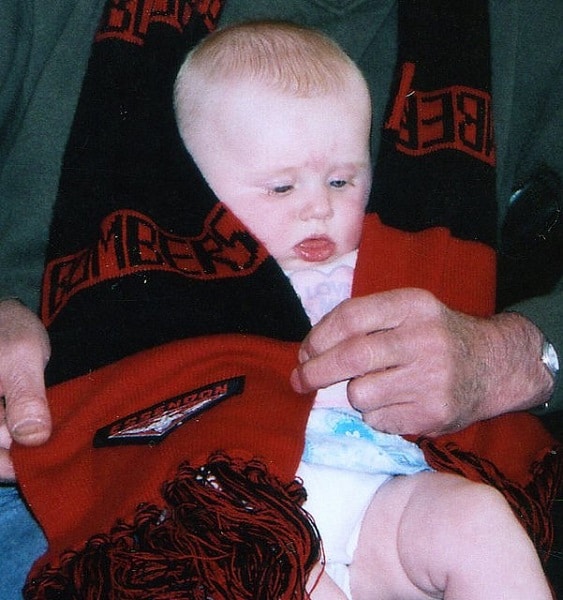

On the other side of the world, in Australia, there are no yardsticks, but there are certainly illogical objects. In a country where the temperature hovers close to a hundred in summer and rarely drops near freezing in winter, most household cupboards contain long, colorful woolly scarves. These look perfect for winter in Montreal or Vermont; but on a warm day in Australia, people take them out and wear them down the street.

They are footy scarves: an item of clothing designed to be worn by fans to show the colors of football teams. These scarves have nothing to do with keeping warm. Yet it is expected that people will likely own such a scarf – or the equivalent woolly hat or ‘beanie’ – to express the identity of their team. And everyone has a football team: indeed, What team do you go for? is perhaps the most common conversational question in Australia after ‘what do you do’ and ‘where are you from?’; it is as much a part of an Australian’s identity as their surname or profession.

If Americans in the neoliberal eighties all had a yardstick somewhere in their domestic realm, Australians – a deeply tribal people – are sure to have a footy scarf in theirs. The yardsticks do not measure; the scarves do not keep us warm. They are illogical, but no one cares. Each is a kind of domestic talisman: something that is kept almost unconsciously, unquestioned. Indeed, not to have one would be nearly unthinkable.

And Now About the Guns

In the eighties nearly every household in America had a yardstick. In the 2000s, it seems, nearly every household has a handgun. Things changed that quickly. Yet when I return for a visit, no one seems to notice. The guns are just there, as if they had always been there.

I first sensed something was wrong when I took my family to America a few years back. We were visiting a cousin, and my daughter, then a toddler, wandered about while the grownups talked. At one stage I lost sight of her up a short flight of carpeted stairs that led to the bedrooms.

‘Is there anything she could get into up there?’ I asked: breakables, makeup, possibly medicine?

‘Oh, said my cousin, up there – that’s where we keep the guns.’

I vaulted upstairs. The tone of the conversation had barely shifted; there was certainly no sense that keeping guns (I did not ask how many) in a bedroom was anything but perfectly normal. Indeed, as we moved from relative to relative, from house to house, I was startled to discover that I was the one with odd ideas about bedrooms and guns.

‘What do you want them in your house for?’ I asked. ‘Aren’t they dangerous?’

‘Of course not,’ my relatives told me over and over. ‘Not if you know how to use them.’

‘And what do you use them for, then?’

The answer was always the same: to protect ourselves. From the point of view of everyone in my extended family – located along a long socio-economic spectrum – guns had become, in a handful of years, an eminently logical household object. Of course, some of the uncles had always had rifles for hunting. But the new object of choice was the handgun: a small thing, capable of being tucked under a bed or into a drawer, pretty enough for a handbag, always nearby.

I disliked the thought of sleeping in houses with guns and relatives who knew how to use them. But this was just a vague concern, a philosophical position, really, so long as they all guaranteed to me that the guns were away out of the reach of my curious child. Until the day my mother commented casually,

‘Yes, your brother came home late one night, and I nearly shot him.’

They laughed: a moment of mistaken identity at midnight, the sort of thing that could happen to anyone. Like when my daughter pointed out the heavy holster slung over the arm of a cousin’s La-Z-Boy:

‘Look, you left your gun out! I’m telling Mommy!’

My cousin hadn’t lied; he had simply forgotten it was there. The show guns, the nice guns, were safely in their cases locked away as promised, but this one was just part of the furniture. I am unsurprised when I read the statistics on America’s killer children – many of them toddlers. I’m sure parent mean to put the guns away. But handguns are illogical objects. They are objects designed to kill, kept in intimate domestic spaces in order to keep people safe. Even when all the data tell us they do exactly the opposite.

A few months back, my brother attended the funeral of a family friend, a girl who returned home from a party after dark and was shot dead by her own mother. Such impossible things seem increasingly frequent in a country that seems more foreign at every visit. From across the water I can see that the domestic handgun is anything but logical. But logic is not the point. The handgun is emotionally powerful: it is a modern talisman. People believe this object will keep them safe, that it will place them in control in a dangerous world. The fact that this does not work is surprisingly easy to ignore.

The power is not in facts but symbols: the gun is kept close, not because of what it does, but because of what it means.

Illogical objects always have a deeper reason for being in our cupboards, in our homes, and entangled in our intimate domestic lives. Anthropologists can show us how to look at objects and hear what they are telling us: about others, and about ourselves. Once we understand this, we can clear the clutter without disposing of things that make us mourn. We can question the objects we take for granted, and unwrap their real purpose. And we can choose: what to keep close, and what has to go.

“Illogical” – I am not at all convinced that this is a good term when applied to objects, What would be a “logical object”? Thoughts, actions, interpretations, solutions, these can in principle be il/logical. But objects? Impractical, useless, redundant, badly-designed, uncomfortable, displaced, sure. I’d be interested to learn why this word was chosen.