When we raise questions about the assumed figures of the ‘smuggler’ and ‘trafficker’, we must also in parallel raise questions about agencies, officers, policies, and discourses of the state. These include enforcement efforts against smugglers, service providers to smuggled people, and those tasked with generating publicity around the issue of smuggling. Additionally, we must question the role of NGOs that mobilise around this issue and that receive state contracts in this domain as well as in human trafficking (e.g., shelters and transition houses).

This is not to say that these activities are always suspect – they may actually be good choices in terms of morality and policy – but such matters need careful consideration.

The state should not be allowed, unquestioned, to hide within the cloak of ideal law against a stereotyped evildoer. Laws are politically formulated, incompletely and selectively enforced, and sometimes ignored, even in the best of circumstances, and such considerations require close scrutiny of actual state activities and rationales. Or, more directly said, we should question the state as much as we question smugglers and traffickers.

Our work delineates the basics of US government actions against traffickers. Since the late 2000s, this has been a growth area amid a stagnant overall budget. For example, from 2007 to the present, the State Department’s Office to Counter Human Trafficking (J/TIP) grew from a budget of $4,119,000 ($4,706,510 in 2016 terms) with 24 permanent staff to requesting $9,329,000 with a permanent staff of 47 in 2016. Yet there is no particular reason to think the issue has doubled over this period of time, though arguably this increase is catching up with an existing phenomenon. Other agencies have similar growth patterns: Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Homeland Security (Coast Guard, Immigration and Customs Enforcement), Department of Justice (FBI), and so forth.

A notable feature is the political side (Congress) driving the expansion of administrative (enforcement and services) action in the trafficking domain. Interestingly, the Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB), a part of the Department of Labor, attempted to reduce its human trafficking responsibilities. Their average funding requests from 2006-2009 were $13,229,750, yet an average of $78,045,000 was granted by Congress. The majority of the funding discrepancies occurred over the role the office was to play in wage theft and human trafficking. The bureau stated it wanted to reduce its efforts to an “advocacy” role, hence the reduction in funding needs, yet Congress sought an expansion of its activities. Our preliminary sense is that trafficking is a politically favored domain of state action. There may be key political alliances between advocates (often formed into NGOs), Congressional staff, and some but not all government agencies that have promoted this expansive path. This needs to be explored further.

Agencies of the state both help propagate the brutal trafficker image and benefit from it. The ‘trafficking’ label does work for the state side: it makes enforcement actions seem humanitarian and compelling, necessary and logical (a solution to a named problem), and it covers over actual complex realities on the state side because it is such a hard-to-question ‘enemy’.

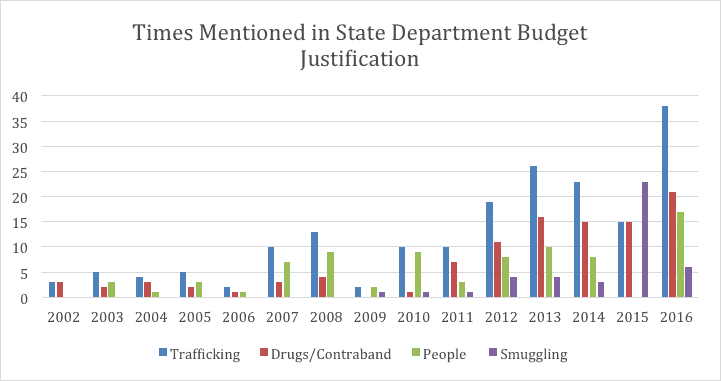

There is also mission creep from anti-trafficking to anti-smuggling, anti-migrant facilitator, and anti-migrant operations. This blurring works to the advantage of police and diplomatic agencies. Because trafficking in people is a simplistic, morally compelling label, it helps justify rapidly increasing budgets. We have systematically tabulated terms used in the US State Department budget requests. For example, while trafficking is indeed the most frequently mentioned justification, more than half the requests in 2016 went outside of trafficking, to include drugs/contraband, the smuggling of people/migrants, and other forms of smuggling.

Alliances between state agencies and NGOs merit attention, as well as alliances between central and local states. Of the pool of $44 million awarded to government agencies in 2015, it was divided as follows: 36% to selected district attorney’s offices, 31% to police forces, 29% to municipal governments, and 4% to the Department of Labor. Across recipient agencies, 33% went to developing task forces, 19% went to task force enhancement and an additional 19% for victim services. The largest non-government recipient of grants was the Salvation Army, with 15% of all NGO funding, much of it passed through local state agencies.

In El Paso, Texas, we have seen some of this process from the inside. In this border city, the Salvation Army has been the driving local force with federal grant money. Local observers find that trafficking in El Paso actually centers on domestic transportation routes, primarily the major highway and truck routes passing east-west through the city. In contrast to this observed reality, the rhetoric of anti-trafficking refers heavily to US-Mexico border migration (south-north movement).

This blurs migration and trafficking. Money is pushed out in ways that reward key NGOs and police agencies: giant billboards (in English) on the main highway with police agency logos. Maybe this is indeed a good way to reach truck routes, but it seems expensive and indirect, and in El Paso use of Spanish is always needed alongside English. Some money has usefully supported a shelter and transition house. Furthermore, the budgetary expansion of the trafficking agency and the moral justification of the cause ‘buy’ local police agencies, academics, activists, and social service providers.

Finally, it is worth noting that the accumulated profits produced by migrant facilitation, smuggling, and trafficking actually provide significant revenues for the state – both local and central – above and beyond budget justifications.

This occurs through asset forfeiture programs, in which seized monies, goods, and real estate are taken by law enforcement agencies and redistributed across local, regional and international levels, buying adherence to the state agenda.

For example, during “Operation Coyote”, an anti-smuggling initiative in 2014, over $625,000 in illicit profit was confiscated from 288 bank accounts. The Immigration and Customs Enforcement asset forfeiture branch, which obtained and passed through these funds, is part of a large family of federal asset forfeiture accounts in the Treasury Forfeiture Fund (TFF), administered by the Treasury Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture (TEOAF). That fund totaled $807 million in Fiscal Year 2014, though certainly not only from human trafficking or smuggling. It is worth considering the multitude of ways that various agencies and levels of the state are fiscally interwoven with criminal or covert enterprises.

Indeed, this should raise in our mind a crucial note of skepticism: governments and various illegal practices, networks, and actors have mutual dependencies and interconnections. They are not just polar opposites, locked into a battle of good and bad. From this questioning stance, we can more openly explore the ambiguous fields of politics, advocates, state agencies and officers, and migrant traffickers, smugglers, and facilitators.

Our co-producer openDemocracy offers more food for thought on human smuggling:

- Beyond common-sense notions of human smuggling in the Americas, by SOLEDAD ÁLVAREZ-VELASCO and MARTHA RUIZ

- Smuggling as social negotiation: pathways of Central American migrants in Mexico, by YAATSIL GUEVARA GONZÁLEZ

- The call to become a smuggler, by LUIGI ACHILLI

- Precarious livelihoods in eastern Indonesia: of fishermen and people smugglers, by

- Governing migrant smuggling: a criminality approach is not sufficient, by ANNA TRIANDAFYLLIDO

- The struggle of mobility: organising high-risk migration from the Horn of Africa, by TEKALIGN AYALEW MENGISTE

- Communities of smugglers and the smuggled, by NASSIM MAJIDI

Featured image (cropped) by Jonathan McIntosh (flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)