Let me start with a confession: Throughout the past year or so I have become somewhat hesitant to attend conferences and other academic gatherings. This sense of reluctance has little do with the form or content of scholarly debates, or the need to discuss my work. Rather, I am finding it increasingly difficult to “digest” the coffee and lunch breaks, the moments in between, when participants shift from focussed discussion to social talk. One core subject of debate seems to reverberate through the hallways of university buildings around the world: The insecure and unsustainable working conditions we are all struggling with in our daily lives.

When socialising with other precariously employed colleagues, the conversation quickly moves to the depressing conditions of our academic existence. We routinely exchange the latest horrors of the anthropological employment market: “Have you heard that 150 people applied for the one rare job opening at the university of so and so?” “The chance of getting such and such grant is ten per cent.” “My one year postdoc contract, the reason why I moved to this and that country, runs out the end of the year.” “Is it true that the post of Professor X in XY will be axed after his retirement?” We endlessly discuss the dreary figures, rankings and deadlines shaping our lives, to the point that we cannot but admit that we have become mere puppets in a show that is run by everybody else but us. The whimsical rules of the funding and university bodies that those of us who have decided to participate in the “academic game” live by, leave us with the growing realisation that the cost of playing this game is that we have given up control over our futures. Moving from short-term contract to short-term contract and from one academic system into the next,

the future has turned into a threat rather than a promise, into something that is always within our grasp and yet so impossible to get a hold of.

The perverse inversion of this desperation talk also echoes through university hallways. It shows in the proud talk of how many hours we work, the name-dropping, the creation of webs of contacts we hope will be able to support us in one way or the other, the publication targets and rankings, and so on. In such a ruthless and competitive environment, it becomes easy to look down at those who do not make it and see them as not good or tough enough, as not “cut out” for academic life. When everybody’s job is on the line it is hard not to become cynical and cruel to oneself, all the while knowing that you could be next. How impossible the academic game has become can be seen from the growing number of confessionary blog posts circulating in the Internet, in which scholars make public their decision to resign from academia. As Francesca Coin (2017: 705) writes, in this new genre of “quit lit”, the act of resigning from an academic position is about much more than just quitting a job:

It is a symptom of the urge to create a space between the neoliberal discourse and the sense of self; an act of rebellion intended to abdicate the competitive rationality of neoliberal academia and embrace different values and principles.

After such moments of shared commiseration – or “comparative misereology”, as Mariya Ivancheva from the University of Leeds so poignantly put it during one of the workshops in Bern – I often feel at a loss how to move on. Having (yet again) spent so much time and energy discussing my own sense of precarity rather than the precarity faced by the young people my research focuses on, I feel guilty, angry and deflated all at once.

I feel guilty because I know that the sense of insecurity I am discussing in the university corridors seems miniscule compared to the economic, social, educational and existential uncertainty in the lives of the people I am working with – refugee youth from countries marked by protracted and violent conflicts who have borne up against the greatest odds to make their way to Europe across deserts and oceans, without parents or other adult guardians in the hope for better futures, and who now find themselves struggling to identify a way forward in an unrelenting asylum system that does everything it can to kill their hopes.

I feel angry because the pulling effect of the neoliberal educational game manages to have such a bearing on us (so-called) young academics that it succeeds in diverting our attention away from the grave experiences of uncertainty, exclusion and anxiety many of us witness in our research.

And I feel deflated because I wonder how I am to find the inner motivation to return to my office desk the day after such acts of collective lamentation and do justice to the stories and experiences of the young people whose pathways I have been following for over two years. How to write about their struggles to find acceptance and build towards a future in a wealthy country where right-wing and anti-immigrant rhetoric has long become such an accepted part of politics that exclusionary language and practice have become woven into the texture of the everyday? Given that I am writing from the position of a postdoctoral academic who has dragged her husband to the other side of the globe, a country we both have no social ties to, for a postdoctoral position that will end in a few months time, I ask myself how to write about the trajectories and experiences of the young people without projecting too little or too much hope into them. How to write about, think and analyse precarity from a precarious position? Is there a link between the kind of precarity my colleagues and I are struggling with and the precarity of the people we work with? Is there, in other words, a link between political and economic precarity?

Until quite recently I would have refused to engage in such a thought-exercise. The danger of overwriting my research participants’ grave experiences of hardship, violence and displacement with the comparatively miniscule uncertainties I am faced with in my daily life seemed too dangerous. Yet the papers presented at EASA’s Annual General Meeting in Bern provoked me to think more deeply about the links between different forms precarity – or, to be more precise, different modes of precarious being. The conference offered an excellent basis for this as it brought together a tapestry of academic voices demonstrating the manifold ways precarity reaches into their lives: The presentations ranged from the social and political precarity experienced by scholars who have been silenced by authoritarian regimes, to the social, political and intellectual costs of defending knowledge that has become “dangerous” (Özlem Biner, keynote), and finally to the anxieties and fears of young scholars wrestling with educational systems that seem to be determined to cast them off as soon as possible.

While the struggles of each of these groups is unique and deserves to be understood in their own complexity, the gathering in Bern made it clear to me that it is equally as important to understand their interconnections. As Sarah Green pointed out in her reaction to one of the papers, one of the difficulties of the current rise in precarity worldwide is that it has created fragmentation across countries, groups and individuals, thereby making it almost impossible to find common ground from where we could act or argue. Yet, while the precarity experienced by academics in Turkey might seem to be a far cry from the precarity experienced by a young scholar in Germany or Ireland caught in the postdoc hamster wheel, it is important that we come to understand the underlying ontological and structural conditions linking them.

This became particularly clear to me as I was listening to the presentation of Aimilia Voulvouli, currently a postdoc at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, who had been confronted with both economic and political forms of precarity within a very short stretch of time. In 2009 she lost her position at a Greek university as a result of the financial crisis – like 90% of her colleagues. In a conversation after the workshop Aimilia emphasised that this mass-termination of university positions was not solely driven by neoliberal austerity measures. Rather, the “crisis” was often taken as a pretext to get rid of critically engaged academics, with anthropologists being amongst the first ones to be let go. With no chance of finding employment in Greece she decided to look for work in Turkey, a country she knew well from her previous research. Ironically in hindsight, Turkey was able to offer much more secure and stable working conditions to academics than many other European countries. With the increased authoritarianism and crackdown against dissident voices after the failed coup in July 2016, however, Aimilia found herself confronted with yet another form of precarity, this time primarily political. Like thousands of other academics who had worked at institutions that had close links to the Gülen movement, she lost her job.

Resembling the tactics of neoliberal pretence-speak many of us who have received rejection letters from funding bodies know all too well, the official reason the authorities gave Aimilia for the sacking was not her political position. Instead, the council of education based their refusal to renew her contract on a clause in the law stating that universities were not allowed to employ more than a certain amount of foreign nationals and that they had reached the annual limit. Knowing that she would put herself in danger by challenging the government’s decision, she packed her bags and returned to Greece with a feeling of defeat. “It was like a déjà vu”, Aimilia explained to me. “Yes, in Greece I was fired because of financial reasons – financial austerity – in Turkey for political reasons, but in the end of the day the result is the same. In both cases it was beyond my control.

And this is what precarity is about: That you don’t have the means to control your own life.

Aimilia’s story flung open a window for me to seeing the importance of understanding the connections between the different modes of precarious being. Her insistence that the economic precarity she faced in Greece and the political precarity she was confronted with in Turkey appeared to her in exactly the same way (namely through the lack of control), made me realise that the underlying ontological condition shared by people in various states of precarity has the potential to create common ground amongst disparate and fragmented groups and people.

In a response to the panel where Aimilia presented her paper and story, Julia Eckhart urged us to understand precarity as a disciplining power. While the techniques of disciplining might differ from country to country and from context to context, they bring about the same result: The fear, uncertainty and lack of control that becomes woven into the fabric of our intimate lives, thereby initiating acts of self-censorship, conformity and silencing. Paradoxically the hopelessness and uncertainty marking these various disciplined modes of precarious being across the globe forms the potential for the creation of new hopes. Despite the gloomy picture the presentations painted about the current state of academia and the world at large, I agree with Alberto Corsin Jimenez who noted the remarkable return of a particular notion throughout the discussions in Bern that seems to have almost slipped out of anthropological debates in recent years: Solidarity. With the current backlash against liberal democratic values and the rise of authoritarian and anti-intellectual politics, it becomes even more important that we create webs of solidarity across borders, classes and groups.

This does not mean that we should appropriate the precarity of the people we study. My own precarity is not determined by the same rules and logics as the precarity of the young refugees I am working with. Yet the specificity of different modes of precarious being should also not create a situation where each of us is forced to stick it out on our own, exiled in our individualised little hells, thereby forfeiting the possibility of dialogue and (by extension) change. My ability to study and critique governments and corporations that profit from the conflict that has driven the young people from their homes, or that keep them in a calculated state of precarity in exchange for popular votes, becomes crucial to maintaining open and democratic societies. We cannot have our own states of precarity undermine this crucial ability.

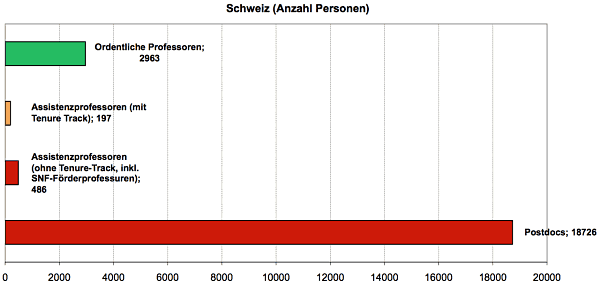

The event in Bern brought home to me that we are well past the stage of diagnosis. What is needed now is not up to some opaque external powers governing our lives and futures from afar. It is up to us, each of us. The narratives of comparative misereology reverberating through the hallways of universities need to be turned into the grounds for solidarity and action. And the chances of succeeding are not too bad: When Sabine Kradolfer, an anthropologist from Neuchatel, presented a chart depicting the crass imbalance between permanent and temporary positions in Swiss academia, a sigh of disbelief went through the audience (see graph 1). Yet, as Dan Hirslund from the PrecAnthro group remarked, instead of seeing the graph as a depiction of the success of neoliberal educational policies, which have drained universities of funding and created an army of precariously employed academics, we should look at it from another perspective. We should see the over-representation of the red bar (meaning precariously employed postdocs) as “revolutionary potential”.

Rather than viewing our (at times desperate) situations in isolated terms, we should begin to think and act collectively.

And this solidarity should not just encompass the securing of our own jobs and futures. Rather than succumbing to the confessionary mode of commiseration that has rendered many of us paralysed and speechless for far too long, I believe that there is something to be gained from writing, thinking, and theorising precariously. By taking our own modes of precarious being seriously, by transforming the multiple insecurities undermining our life conditions into writing and thinking, we can create new analytical lenses for understanding our interlocutors’ modes of precarious being.

Writing and thinking precariously is about taking a political stance against the disciplining techniques that seep into people’s everyday lives and do not just create precarious individuals, but socialities (Khosravi 2017: 4-5). It is about finding a shared language that is able to speak up against the negative grammars of individualism and self-abuse so many of us across the globe are currently caught up in. Finally it is about cherishing and protecting the “dangerous”, or “poisonous” (Das 2000) forms of knowledge we as anthropologists produce.

References

Coin, Francesca. 2017. ‘On Quitting’, Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organisation 17(3): 705-719.

Das, Veena. 2000. Violence and Subjectivity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Khosravi, Shahram. 2017. Precarious Lives: Waiting and Hope in Iran. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.