Why do images matter? How is it that these assemblages of pixels and ink come to shape not only our own view of ourselves, but also of the world around us? How might we be able to understand visual logic as something not illustrative of but distinct from textual logic? How much influence do images really have and how much significance should we, as social researchers, give to images? What, in short, is our relationship with images?

“A picture is worth a thousand words” – One of the English language’s most popular tropes, this popular phrase translates seamlessly into many other langues (“Ein Bild sagt mehr als Tausend Worte”, “Una imágen vale más que mil palabras”). It intuitively seems to make sense. After all, we do know that images are powerful. Goffman (1979), for instance states that images can provide us with “’an actual picture’ of socially important aspects of what in fact is out there”

Images are everywhere. The technological part of taking images has become rapidly easier throughout the 20th century. Image focussed social media surrounds us. Many people actively create their identity by carefully curating their visual online presence. These images say “something about who we are and how we want to be seen” (Rose 2016: 46).

In our daily communication, words are increasingly replaced by emojis, memes and gifs [1]. This heavy use of visual aids in our digital conversations may lead us to believe that Semioticists are on to something, that a picture is not only worth a thousand words but that the two are interchangeable, that images can be deciphered to reveal coded messages, that they are in fact a language.

However, images are also notoriously misleading.

Ironically so, one might argue since we still tend to think of images as photographic evidence and fetishize photographs of things we might otherwise find hard to believe or to prove (say, Bigfoot, or a celebrity cheating on their spouse). But for all their appeal, pictures often have little to do with ‘truth’. A picture may be worth a thousand words – but which words? While increasing use of Photoshop both by professionals and amateurs may have put our blind faith in photographs into perspective, a picture does not need to be actively altered to mislead its audience. Sometimes, just putting an image into new context can be enough for a distorted, emotional association to penetrate our judgement long before our rational mind can catch up. Again, and again we find ourselves ‘tricked’ by images, be it in the form of advertising, our political choices, our self-image, or our perception of truth. Think, for instance, of the iconic ‘Breaking Point’ Brexit campaign poster used by Ukip to stir fear in voters, despite the fact that the people pictured had nothing to do with refugees trying to come to the UK.

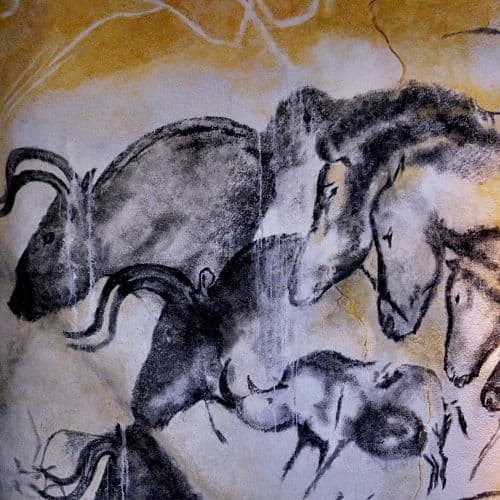

The oldest evidence of a human relationship with the image we have found so far is 32 Thousand years old. Nonetheless, we are still somewhat struggling to find a coherent distinct way of talking about images across disciplines.

Are images data, method or end product?

Images can be turned into data themselves, such as Cornelia Brink´s (2000) study where she treats images from Nazi concentration camps as data by analysing the image and its reception making an argument about iconography.

Examples of images being used as method include Douglas Harpers work on photo elicitation in interviews (Harper 2002) or his visual ethnographies (Harper 2012; Pink 2007).

In the realm of Social Sciences, the discipline most prone to use visuals as an end product may well be anthropology. There is no shortage of reflexivity over the ethnographic films made by Anthropologists (For a great overview see Jay Ruby’s Picturing Culture (2000)). Hastrup (1992:10) argues that film is “thin description”, that film, as a mechanical unit cannot live up to the qualities of the observer’s eye. Others, for example Suhr (2012) and Willerslev (2012) argue that it is precisely the way in which the camera differs from the human eye which allows for a mode of communication which transcends that of the written word. Bill Nichols (2007) identifies 6 distinct modes of representation (expository, poetic, observational, participatory, performative and reflexive).

It is only more recently that scholars have begun to take more integrated approaches to the Visual, considering it as deeply enmeshed with sociality, performativity and experience – examples include Anand Pandian’s Reel World: An Anthropology of creation (2015) which, by considering Indian film sets, gives us an insight into what it feels like to inhabit the realm of cinema; or Tim Ingold’s edited volume Redrawing Anthropology (2011) which explores the connection between anthropological processes and visual material practices.

In this thread we have no comprehensive answer to what images are or what they do. Instead, we bring a multiplicity of approaches to the subject with each post casting light on a different level of our relationship with images, exploring a variety of subjects where visuals are in some way central to our way of making sense of it (things).

In the first post, Ilona Suojanen shows how images create data which is distinct from text based responses. In her studies of happiness at the workplace she collected data by asking people to take pictures of what made them happy. Those images, when analysed provided different information than traditional surveys. This, she argues, is not to suggest, that one method is superior to the other but rather that they produce different ways of answering questions about happiness.

Nichole Fernández, in her post Images Matter, discusses the power seemingly benign images can have over us. Through her research on Croatian Tourism advertisements, she shows that images have effects on the social world and the construction of identities. She argues that researchers need to ask questions about not only what an image is saying but also what it is doing.

Following on from nation branding, Arek Dakessian interrogates some of the invisible, implicit values underlying advertisement images. Drawing upon a 2014 Lebanese nuts ad, he observes a disconnect between producers and consumers and reflects upon its implications. He argues that, in effect, this disconnect reproduces processes of othering, all the while plasticizing social stratification and hollowing out politics from social class.

Mairi O’Gorman, in her post Visualising the past: crafting respectability in Seychelles and London argues that the visual is fundamental to everyday life in Seychelles. She describes how particular aesthetic conventions help Seychellois to maintain a connection to an idea of what it means to be Creole, and enable them to process a history that is often painful. While carrying out fieldwork in Seychelles and London, she realised that this way of approaching history through visual artistry and textiles was part of her own upbringing, and intends to use these techniques to deal with her data.

The final post in the thread by Aglaja Kempinski uses ethnographic material from an Edinburgh Tattoo shop to explore how people inhabit images. She argues that rather than images being a way to capture something, to pin something down, they can help individuals to be more flexible in how they relate to and express their experiences.

While some of the posts point to a difference between images and words, we do not mean to suggest that there is an inherent dichotomy at play. Images and words exist in relation to one another. When visually presented, for instance words become part image – consider the different effect of a document written in Comic Sans to one written in Times New Roman. On the other hand, words often become part of images – for example as parts of tattoos or logos. Further, words are often arranged to be evocative of images and prompt a picture inside our minds.

The goal of these posts is not to disentangle these relationships or to negate the ways in which the two are intertwined but rather to focus on what the visual brings to these relationships. What we aim to provide are examples of taking images and their sometimes paradoxical and incommensurable ways of affecting us seriously.

References:

Brink, C., 2000. “Secular Icons: Looking at photographs from Nazi concentration camps”. History and Memory. 12(1): 135-150

Goffman, E., 1976. Gender Advertisements. London: Macmillan

Hastrup, K., 1992. Anthropological Visions. In: P. &. T. D. Crawford, ed. Film as Ethnography. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 8-25.

Harper, D., 2002. “Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation”. Visual Studies 17(1):13-26.

Harper, D., 2012. Visual Sociology. New York: Routledge.

Ingold, T., 2016. Redrawing Anthropology. 1 ed. London: Routledge.

Nichols, B., 2007. Representing Reality: issues and concepts in documentary. 9 ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Mitchell, C., 2011. Doing Visual Research. London: Sage.

Pandian, A., 2015. Reel world: an anthropology of creation. 1 ed. Durham: Duke University Press.

Pink, S., 2013. Doing Visual Ethnography. 3rd ed. London: Sage

Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies. 4th ed. London: Sage.

Ruby, J., 2000. Picturing Culture: explorations of film and anthropology. 1 ed. Chicago; London: The University Press of Chicago.

Suhr, C. &. W. R., 2012. Can film show the invisible?. Current Anthropology, 53(3), pp. 282-301.

[1] Check out this robot that only corresponds in gifs

Featured image (cropped) by Thomas T. (flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)