John Adair and Sol Worth, American anthropologists and filmmakers, found themselves in the sticky situation of answering the above question in 1966. They had just presented the leading elder of a Navajo community, Sam Yazzie, with the idea of teaching several Native Americans from his community filmmaking.

‘Will making movies do the sheep good?’

Worth was forced to reply that as far as he knew, making movies wouldn’t do the sheep any good.

Sam thought this over, then, looking around at us he said,

‘Then why make movies?’

Adair and Worth were intending to teach their students some basic filmmaking skills so they could find out how another culture might conceptualize the grammar of filmmaking differently, thereby researching culture-bound ways of representation. The project continued, but Sam’s concern remained unanswered. However, it revealed some important issues that visual anthropologists as well as documentary filmmakers should reflect upon with every film they make: What and who do we make films for?

Ethnographic filmmakers straddle two worlds. On the one hand, they become filmmakers dedicated to building a narrative that reaches an audience and reflects how they see the world. On the other, they are anthropologists who approach modes of representation as well as issues of control over production and distribution of films with a cautious eye.

Visionary filmmaker Jean Rouch, linked to both anthropology and the more glamorous New Wave of French Cinema, declared that he made films firstly for himself. Secondly, he considered his primary audience the protagonists of his films. To him film was primarily a way of communication between himself and his subjects. How to approach the pitfalls of representation is a matter for debate: some argue that observational cinema is the way, while others look towards montage as the next step in anthropological filmmaking. Yet, there is another radical way. Again, Jean Rouch foresaw that with the new technological developments, ‘the anthropologist will no longer monopolize the observation of things’. So in visual anthropology, what if we let go of our pride in being ‘the author’ and start collaborating?

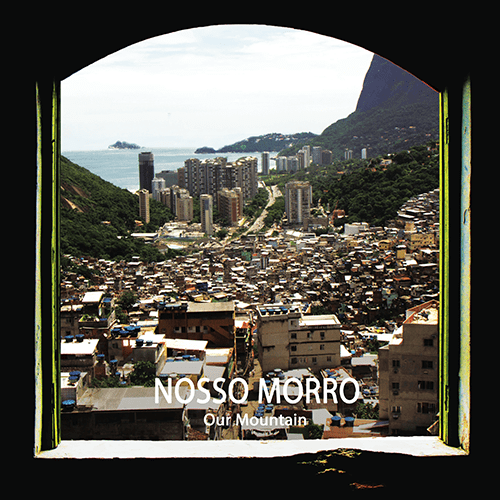

With this in mind, Nosso Morro came into existence. The collaborative project in which we, six young visual anthropologists from The Big Tree Collective, tried to teach some filmmaking to a group of teenagers from Rio de Janeiro and shoot a collaborative film in the span of a few months. Our quite ambitious project included collaboration between participants of different ages, cultural backgrounds and economic status, as we were planning to bring together teenagers from the Rocinha favela of Rio de Janeiro with youths from the wealthy neighborhood of Gávea. The idea was to explore the differences and common experiences of teenagers who inhabit the same geographical space (the same street) but very different social spaces.

To describe some of our experiences to you—and to give you a better idea of collaboration in research and creation—two of us, Clara Kleininger and Daniel Lema, are co-writing this article. As an experiment we decided to compare fragments of field notes and later recollections regarding the most important moments of creating the workshop and the ethnographic film Nosso Morro.

Clara:

Almost a year ago, my colleague proposed a visual anthropology project in Rio de Janeiro. The idea stemmed from her personal experience: she grew up in Rio and went to school on Gávea street, the same place she wanted to explore through the Nosso Morro project. To me these were already good preconditions to start a promising project. Although we discussed some preliminary ideas, we did not decide upon a certain narrative for the film. We wanted to include the teenagers into the process of creating a film narrative.

Daniel:

In November 2015, I arrived to Rio de Janeiro as a member of the visual collective The Big Tree. Almost everything in the project had been discussed and researched: we had found a hosting institution where the workshop would take place, local partners, potential collaborators, teenagers from local communities willing to participate, etc. In short, the goals seemed to be clear and we had a sort of production plan.

Clara:

Initially we planned to split the workshop in between the EARJ (American School of Rio de Janeiro) in Gávea, an expensive gated school, and one of the schools in Rocinha. In the end it turned out impossible to find a higher education institution in Rocinha, as the teenagers from Rocinha go to several public schools, none of which are in the favela. In my opinion this limitation was a big loss to the project, as it brought a certain imbalance into the dynamic of the workshop.

Daniel:

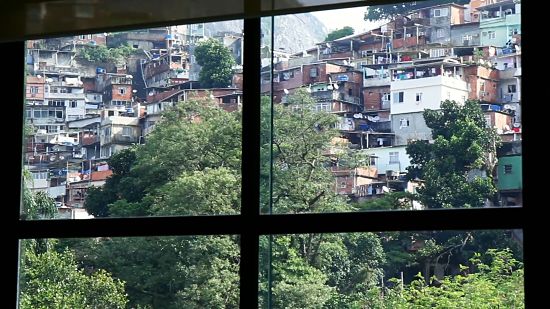

The first contact revealed both the willingness of the ten teenagers to meet each other and collaborate, as well as a variety of social performances depending on their social background. Young people from Rocinha appeared specially dressed up for the occasion of our first meeting on a Saturday, in contrast with the more informal clothing chosen by the students from Gávea. Indeed, not only outfits of Rocinha teenagers seemed to express a kind of courtesy or deference towards the institution they were entering, but also the attitude they showed, which was especially shy. Entering the EARJ school for the first time as an outsider (coming from Rocinha or from Europe) can be a quite intimidating experience. The high walls of the EARJ are crowned with barbed wire and CCTV monitors, the armed security staff at the checkpoint, or the bulletproof glass of the classrooms from which you see Rocinha on the opposite slope are part of the safety measures built for the intimidation of outsiders. Thus, while teenagers from Gávea had only to overcome the strangeness of the other, Rocinha teenagers had to overcome both the strangeness of the new people and a place which revealed its own performative apparatus.

Clara:

Our first problem was defining the main focus of our project. Was it teaching ethnographic filmmaking—and teaching it well—so that the teenagers would later be able to use these skills? Or was the workshop just an introduction to finding the best approach to collaborate on a film and have a concrete, presentable outcome that may be used for screenings in and outside of the community?

Daniel:

Despite the enthusiasm of the participants there were problems scheduling the weekly meetings, due to difficulties in reconciling the project with the everyday lives of the participants, part time jobs among Rocinha teenagers, homework and extracurricular activities for Gávea youngsters. Once the agendas were coordinated we started the development of the workshop. The learning objectives of it were bidirectional. First, the participants would get some basic theoretical lessons in audiovisual language, as well as hands-on knowledge on camera and sound recording skills. Second, the participants would enrich their understanding of each other and their distant yet geographically close communities. And third, we expected to be able to gain some insights regarding their communities through which we could develop a story for our documentary.

Clara:

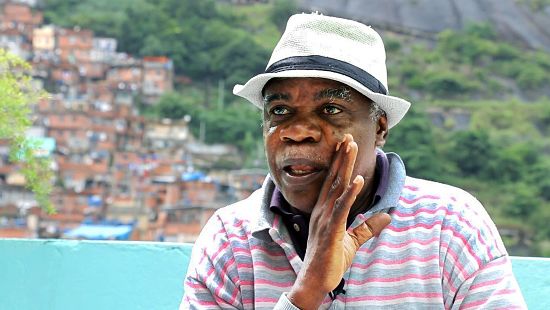

In the end, after a short period of teaching, we focused on making a film, leaving the scriptwriting to the participants (guided by our questions), in an attempt to be as open and exploratory as possible. Our participants were used to school dynamics, so us asking what is important to them was often understood as a test of whether or not they could best guess what we want to hear. But this was also an encouraging sign of their motivation towards the project. They came to the meetings and worked hard and seriously. Each of them vouched for the project, convincing people around them, who were involved in community activities or had valuable experiences, that the project was worthwhile and they should be a part of the film. Due to our reluctance to guide the narrative and to the usual difficulties of planning documentary filmmaking, after the filming period we ended up with a eclectic collection of characters and situations. Although these all revolved around Gávea street, and in spite of an effort to press them all into one narrative, it seemed impossible to put the puzzle together.

‘WHO DO WE MAKE FILMS FOR?’

Clara:

The main topic of the film remained, as we had planned it, working out the divisions as well as the meeting points of Rocinha and Gávea. Although the teenagers worked hard on finding common spaces, like the football game between the teams of Rocinha and the American School, or the prestigious ballet school that gives stipends to good dancers from Rocinha, interactions between the two social worlds were, as could be expected, few. But what our participants tried to constantly show us, was that these interactions, which have been growing during the past years, can begin to be respectful, even though they are still steeped in prejudices and unfair power balances.

At first we intended the participants of the workshop to edit the film themselves, but due to both time and equipment restrictions, our collective edited the rushes with regular feedback screenings to the participants and a lot of negotiations among each other.

We tried to follow the script that the participants had built and edited a first version. It soon turned out that the most valuable part of the project went missing through this. We reconsidered everything and decided to include the process of creation that took place during the workshop, which we had documented all along, into the final edit. In this way we built a film that gives insight into the relationships between the participants of this collaboration but also, more generally, into the specific dynamics that audio-visual media can trigger during research.

Daniel:

In trying to represent the dreams and opportunities of the communities of Rocinha and Gávea, we realized that the filmed workshop had to represent a ‘common place’ in the film: a familiar site to which the viewer could come back in order to follow the negotiation for the creation of the story, as it was in the actual experience. Like this, the final film would not merely be a product of the workshop, but rather a process created through the workshop. Therefore, by

using the workshop as the narrative thread we were able not only to tailor some kind of narrative and make it progress, but also we were capable of adding a new dimension of meaning to the film: that of self-reflexion. In other words, the visibility of the stitches became apparent. These reveal the participatory/collaborative methods employed and work as far more than mere cutaways, transforming the creators—us and the teenagers—into subjects of our own creation, thus providing a new reflexive framework upon which the lived experience and the created filmic experience could meet.

A last thought to conclude. MacDougall (1998:11) contends that film is less a communicative act than a form of commensal engagement that implicates subject, filmmaker and spectator alike.

In this light we see our collaboration as worthwhile. Not only for leaving those who participated with concrete knowledge and experience in a field that interested them. And also not just for bringing unlikely companions together and making a small step–even if just on a micro-scale–towards dialogue between the two neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro. But also for what resulted, a film that does not quite fit into the Western notion of narrative progression, but breaks perspective and representation into many smaller, disjointed points of view. We had to confront ourselves with our own expectations of what ‘a film’ should be and discard them, trying to build something new together.

Proceeding this way in the future, we might learn about a whole deal of new perspectives, not just hidden information, but things as innovative as looking beyond the Western ‘blind spots’, as the division between fiction and documentary or the conflict structure Western narratives tend to base upon.

It is between the three actors MacDougall mentions –viewer, subject and maker- that we, as researchers and anthropologists, have to engage with the other two ones in more challenging and experimental ways than that offered by conventional paradigms and narratives.

Nosso Morro (2016)

37 minutes

Director: Benjamin Llorens Rocamora, Clara Kleininger, Daniel Lema, Paloma Yáñez Serrano, Stefania Villa and Spyros Gerousis

Produced by The Big Tree Collective

Official Selection: Ethnographic Film Festival of Quebec

Conferences: Visual Participatory Methods (Paris), MMU PRG conference (Manchester), Göttingen conference.

Facebook: @nossomorroproject

References

MacDougall, D. (1998). Transcultural cinema. Introduction by Taylor, Lucien (ed.) New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Rouch, J. (2003). Ciné-Ethnography (Feld S., Ed.). University of Minnesota Press.

Worth, S. and Adair, J. (1972). Through Navajo Eyes. Bloomington, Ind.