Since the early 2000s, coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the recruitment agreement between Austria and Turkey in 1964, there have been increasing initiatives in Vienna that involve municipal institutions to capture the (hi)stories of labour migrants, the so-called ‘guest workers’, as integral part of the city’s memory. For example, in 2015-16 the Wien Museum, a key institution for the city’s memory, hosted the project “Migration Collection” (Migration sammeln). The recurring difficulties regarding the acquisition of objects for the collection reflect the tensions inherent in the musealisation of migration (hi)stories and their transition into the city’s officialised canon. Particularly the differences in value attribution (and role allocation) among the various stakeholders involved, such as the museum with its specific criteria for collection, on the one hand, and migrants as bearers of (hi)stories and possible object donors on the other hand, highlight the complexities in the process of revaluing previously neglected pasts. The seemingly neat and stable distinction between heritage as valued and waste as disposable pasts becomes unsettled.

Migrants as bearers of (hi)stories and possible object donors.

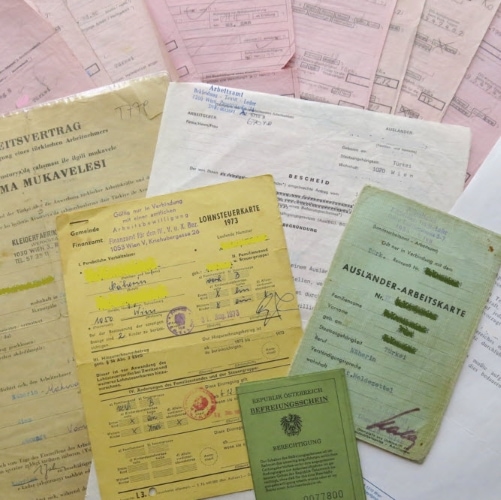

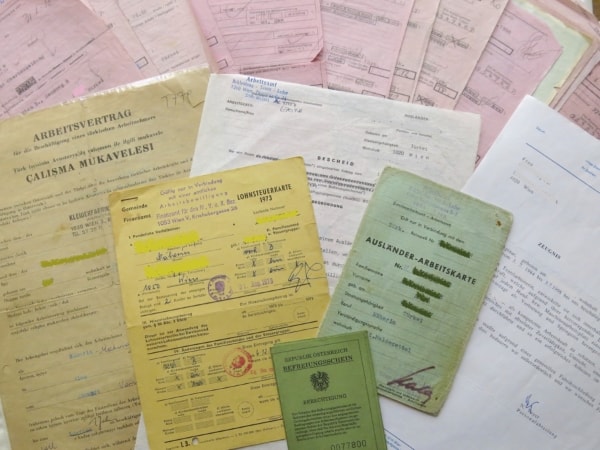

The discrepancy between the objects which the museum envisioned as valuable for collection and display and the objects which labour migrants themselves considered worthy of keeping resulted in a perceived ‘lack’ of representative objects for the “Migration Collection”. The museum prioritised aesthetically appealing, multidimensional objects both in intangible and tangible ways. Objects should thus transmit complex (hi)stories in order to be applicable to a variety of contexts and hence exhibitions. And, most importantly, they should not constitute two-dimensional ‘flat goods’ (Flachware), like documents, letters, and photos. In the context of migration, however, it is commonly ‘flat goods’ that are imbued with high personal value, such as portable memories from ‘home’ in the diaspora, correspondence across geographies and of course the paperwork emerging from the bureaucratic processes of residency, work permits and citizenship. For example, when the mother of one of my interlocutors decided to move back to Turkey upon retirement, she handed over several paper boxes of documents to her daughter. Treasured and stored carefully as inheritances from her mother, the boxes enjoy space in the living room like regular furniture. Yet, the abundance of these two-dimensional, paper objects rendered them even less valuable to the museum, whose criteria for selection also require the object to hold a certain element of rarity and originality. Thus, the museum’s imagination about which objects should be preserved as museal representations for labour migration to the city of Vienna was often at odds with the objects emerging from migrants’ living realities.

The criteria for selection require the object to hold a certain element of rarity and originality.

Moreover, the often cramped housing conditions and frequent changes of residence of labour migrants impacted severely on storage space. As a result, many objects considered ‘relevant’ nowadays by those institutions shaping the narratives on the city’s memory have already been thrown away. As one interlocutor told the collection team of the “Migration Collection”: “We didn’t know that this would be of value one day.” (interview, 2015) Consequently, objects that have in fact endured these adverse circumstances and have been guarded for decades tend to hold a high emotional value. For example, objects that eventually became part of the “Migration Collection” include a cooking pot, which the donor had bought from her first salary in Vienna, as well as a pair of scissors that another donor had used for decades during her employment in Vienna’s textile industry. The range of what may constitute an object of migration is thus nearly unlimited, as long as the object narrates particular experiences or memories of migration from the donor’s life and can be generalised into the larger historical context. Again, not all objects that are considered by their individual owners to hold a specific meaning met the museum’s collection criteria and were thus not approved to enter its collection. The difficulty for the museum to acquire objects it deemed suitable for a collection on migration thus relates not only to the sometimes diverging value attribution to objects by the museum vis-à-vis migrants. It also relates to the fact that the museum’s ‘sudden interest’ in migration arose in a situation in which for addressing the gaps in its collections it had to rely on the participation of migrants, whose existence and (hi)stories the museum had long neglected and treated as disposable. The revaluing of migrant (hi)stories by the museum thus highlighted not only a lack of representation in its previous collections, but also the absence of a relation to a significant part of Vienna’s population.

To complicate this even more, in opposition to what the museum defined as two-dimensional objects, multidimensional objects do not allow for the option of preparing a copy for the donors before being handed over permanently to the museum. This aggravated the collection team’s discomfort in asking for the donation of objects. As a team of five, all active as academics and/or activists, who had been hired to conduct the project, they had to navigate the ambivalences of the project, which they themselves considered both flawed yet also an important step in the right direction. That the donated objects would be preserved and (temporarily) displayed in the museum, moreover in one of Vienna’s key institutions for the city’s memory, did not always constitute a value or sufficiently convincing argument for people to donate objects, they realised. In light of the institution’s long, multi-layered neglect of migrants as an audience to be considered, as staff members to be hired, or as residents whose (hi)stories constitute a valued part of the city’s memory, this is not entirely surprising. In the project’s closing exhibition „Geteilte Geschichte. Viyana – Beč – Wien“ (“Moving History. Viyana – Beč – Vienna”) in 2017 at the Wien Museum, space was made for life story interviews with some of the object donors as one way to mitigate the object-centred focus of the project and to extend the possibilities for donors to participate beyond the provision of objects by narrating and interpreting their own (hi)stories of migration.

Thus, various ethical concerns emerge as migration transitions from the realm of being disposable to becoming heritage in the context of the museum. The incorporation of new participatory approaches for building a collection on migration may not adequately compensate for the difficult or even absent relation between the museum and the ‘communities’ it aims to represent, more so because the extent of participation is limited. Particularly these first focused attempts by official memory institutions to recognise migration as integral part of the city’s memory, like the “Migration Collection” at the Wien Museum, may only capture selected traces and fragments of migration (hi)stories and beg the question of whose memories are accessible to the museum. Personal, trusting bonds with potential object donors are therefore key for the collection process, especially as the response among the ‘communities’ was more reserved in comparison to the museum’s enthusiasm about the project. Yet, the collection team also highlighted the importance of not relying exclusively on one’s personal network in order to demonstrate the internal diversity among labour migrants from former Yugoslavia and Turkey, challenging the idea of a coherent community. Another important resource therefore came from people engaged in activist work or holding a leading position within the ‘communities’, for example as chairperson in an association. The resulting collection is thus an assemblage reflecting (hi)stories that were accessible to (and accepted by) the museum, while other stories remain untold.

The response among the ‘communities’ was more reserved in comparison to the museum’s enthusiasm about the project.

After the closing exhibition of the project, the collection was moved to the museum’s storage. Since the goal of the project was to build a collection based on object donations, the collected material was not returned to the previous owners after the exhibition. The perspective of having the collection deposited in the storage added yet another layer of ethical discomfort to the collection. It seemed to undermine the project’s efforts and its declared significance in retrieving the previously unvalued (hi)stories of migration from private homes and often cellars to the public space of the museum. Being temporarily displayed, the “Migration Collection” did thus not become part of the permanent exhibition, although this may still (at least partially) happen, since the Wien Museum has ben closed since 2019 for a comprehensive restructuring process. Out of sight and inaccessible to the public, to what extent did the objects of the “Migration Collection” (and their related (hi)stories) then become part of the city’s memory and heritage? One might ask if its storage may in fact add to forgetting by simply “delegating to the archive the responsibility of remembering” (Nora 1989:13). Not only does the collection run the risk of becoming frozen in time (and essentialised), the museum may consider the theme of migration sufficiently engaged with, a box ticked off. Thus, while for the museum the material transition of the migration collection to its storage may be a sufficient recognition of its status as heritage, other actors – such as members of migrant ‘communities’ – may disagree in the absence of more profound changes. Thus, there seems to be a dissonance among the various stakeholders concerning the question when neglected pasts have become heritage indeed and what the process of revaluing should entail.

Out of sight and inaccessible to the public, to what extent did the objects of the “Migration Collection” then become part of the city’s memory and heritage?

In early 2020 a group of activists, artists and academics gathered, including Arif Akkılıç, Ljubomir Bratić and Regina Wonisch of the “Migration Collection” team, in order to found the MUSMIG collective. In their opening exhibition, they announced the birth of a museum of migration (Akkılıç and Bratić 2020). Focussing on past struggles for its realisation, the museum of migration was turned into a museum object itself. While initially they intended to leave most of the vast exhibition space empty in order to symbolise the absence of a museum for migration, they eventually found the gallery stuffed with objects (and people). Maybe tempted by the title of the exhibition, many visitors showed up with materials they wished to donate to the museum. As opposed to the Wien Museum, they have no (storage) space at their disposal, yet they were being overwhelmed with object donations, highlighting the strong demand for a museum of migration vis-à-vis the lack of political will to realise it. Two aspects seem key here: first, the personal migration experiences of various members of MUSMIG collective and/or longstanding, close relations to various migrant ‘communities’, thereby moving beyond the sometimes narrow association of migration in Vienna with the labour migration of the 1960s, and second, the nature of the collective as collaborative work-in-progress with a wide expertise among its members. Contrary to a museum aiming to address gaps in its collections and representation of the city’s memory, the approach of the collective can be more open-ended and pose fundamental questions towards existing narratives.

Initially they intended to leave most of the vast exhibition space empty in order to symbolise the absence of a museum for migration.

In Vienna, the musealisation of migration (hi)stories thus demands an examination of the “difficult heritage” of the World War II, and Holocaust remembrance more specifically, which has been addressed, for example, by the initiative “#HGMneudenken” (literally, rethink Museum of Military History), in which the MUSMIG collective participates. Increasingly also the lingering colonial and imperial legacies of the Habsburg empire are brought into focus, examining its continued effects for today. Also the anti-Muslim racist discourse of right-wing populists in present-day Austria heavily relies on the remembrance of the sieges of Vienna by the Ottoman army in 1529 and 1683 (Feichtinger and Heiss 2013). Yet in its museal representation, it so far remains a key narrative on the city’s memory without any reference to its use as vehicle for discrimination and racism.

Thus, the revaluing of pasts previously considered disposable is not a straightforward path and certainly not a one-way road. Diversity in perspectives and experiences in a city’s memory cannot be appreciated as long as exclusionary narratives remain unquestioned. In activism and academic discourse, heritage moves from being understood as fixed and permanent towards being in motion. Thus, heritage that has long created a hostile environment for large parts of the population is increasingly being scrutinised and potentially declared ‘waste’ – sometimes by being literally dumped in a river. In examining the underlying structures and historical narratives that have rendered migration (hi)stories disposable in the first place, the focus shifts from an additive approach limited to the inclusion of neglected (hi)stories towards an approach of unlearning that paves the way for (re)learning.

Bibliography

Akkılıç, Arif, and Ljubomir Bratić. 2020 Für ein Archiv der Migration, jetzt! In Sich mit Sammlungen Anlegen: Gemeinsame Dinge und Alternative Archive. Martina Giesser-Stermscheg, Nora Sternfeld, and Louisa Ziaja, eds. Pp. 173-183. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

Feichtinger, Johannes, and Johann Heiss, eds. 2013. Der Erinnerte Feind: Kritische Studien zur „Türkenbelagerung“. Vienna and Berlin: Mandelbaum Verlag.

Nora, Pierre. 1989 Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 26: 7-25.

Featured image provided by author – Annika Kirbis (2015)