“Muslims go to Mecca once, if they are not unnecessarily wealthy (laughing), but people of all kinds come to visit Mevlana [‘s musealized tomb] every year. Why? Because one does not come here only to become hacı (pilgim), but to become love itself (aşk olmak)” (Interview, Konya 2019).

When I asked what becoming love means, the self-identified dervish told me “ah, obviously you are new, and definitely not in love yet”. Because if I were, I would have known that Mevlana’s love is not to be grasped through mental efforts, it could only be felt. He was right in identifying me as a newcomer. This dialogue took place on the first day of my fieldwork in Konya in December 2019, where people from across the globe come to visit the tomb of Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi, the 13th century Sufi Muslim scholar and poet.

The figure of Mevlana extended its influence beyond just Sufi communities and reached a global audience as a result of diverse policies of heritagization on a both national and international scale. First, as part of Turkish Republic’s secularization policies, his tomb, which was part of a Sufi dervish lodge where the community was gathering to perform devotion and rituals (dhikr and sema), was transformed into a museum in 1926. Second, and more recent stage of heritagization happened in the 2000s when his teachings on spiritual love and Sufi rituals attracted UNESCO’s attention as intangible world heritage. Fueling spiritualization both in national and global scale, different waves of culturalization of religious places and practices belonging to Sufism also allowed formation of new genealogies. Historically, the travel to God through a Sufi path has been organized around stages of initiation and graduation within a disciplined Sufi community (Sufi order, tarikat) lead by a spiritual master (şeyh) who is believed to come from Mevlana’s lineage. However currently, the teachings of Mevlana are mobilized by large crowds that are not part of conventional Sufi communities.

His teachings on spiritual love and Sufi rituals attracted UNESCO’s attention as intangible world heritage.

To celebrate his unification with God, every year in December, the Turkish Ministry of Culture organizes the official commemoration ceremonies in Konya, a city that is branded as the “City of Love.” The visits to Mevlana’s tomb during December are considered Mevlana’s love-pilgrimage by diverse spiritual and religious communities. During the love pilgrimage in 2019, I stayed with followers of Abrahamic religions and various spiritual traditions, hippies, shamans, mediums and spiritual healers at a community place that is designed like a dervish lodge. I spend most of my time in lodges where rituals were held and in the Mevlana Museum where pilgrims become aligned with Mevlana’s love.

I suggest that the heritagization processes generated different models of inheriting the spiritual love of Mevlana outside the conventional dervish order. The practice of becoming aligned with the spiritual love of Mevlana through visits to his tomb and participation to rituals and redistributing this energy further generates a model of inheritance that is based on sensing rather than a disciplined community organized around lineage ties or shared geographical and historical references. Framing the energetic interaction with Mevlana’s tomb as a spiritual modality of inheritance allows us 1) to investigate the spatially and historically specific understanding of heritage and 2) reconstruct the relationality between inheritance and heritage that are being cut by the global regimes managing heritage. As Regina Bendix eloquently analyzed, by eliminating connections between ownership and responsibility, the global regimes of heritage broke off the semantic and political links between inheritance (personal) and heritage (political). Although the critical heritage literature emerged out of the interest in studying the tension between the official and unofficial understandings of heritage, it primarily remains concerned with contestation over representations, and engages mainly with material places and secularized forms of analysis. The motivation of my research is to think about heritage through a shared capacity of sensing that is imbued with a political sensibility. To illustrate how inheritance of spiritual love is materialized among love-pilgrims, I first give a brief account of the heritagization of Mevlana’s tomb and then invite you into an ecstatic ceremony based on repeatedly chanted prayers (zikir) and the bodily prayer of whirling (sema) where the spiritual love is both inherited and redistributed.

Heritagizing Mevlana

Situated at the crossroads of different culturalization and heritagization processes, and operating simultaneously as an ethnographic museum, a shrine, and a pilgrimage site, Mevlana’s tomb offers a complex puzzle that destabilizes the categories of religious and cultural heritage. Although love-pilgrims gravitate around an understanding of spiritual love that does not fit either into the culturalized frameworks (offered by the Mevlana Museum and UNESCO) or to the Neo-Ottoman fantasies of the Turkish government (dominating the official commemoration ceremonies) the politics of heritagization had an effect in shaping diverse ways to relate to the material heritage accorded to Mevlana.

Mevlana’s tomb offers a complex puzzle that destabilizes the categories of religious and cultural heritage

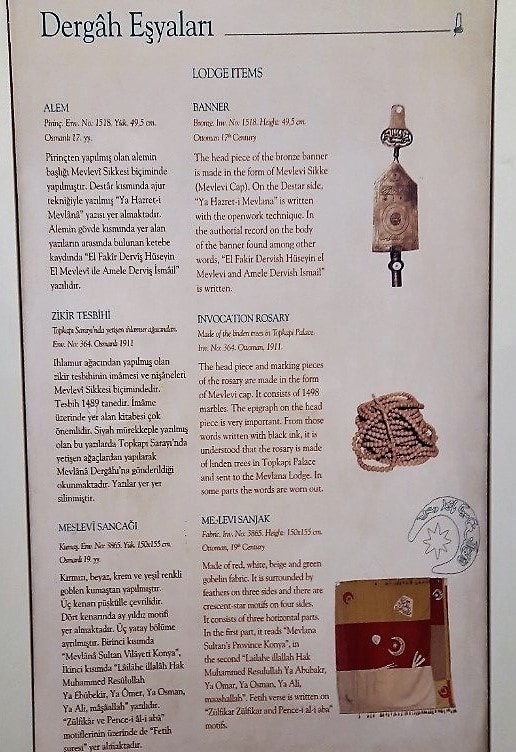

The history of culturalization of Mevlana’s tomb is as old as the history of the Turkish Republic. Considered the traces of imperial legacies, sacred sites such as tombs of saints, dervish lodges and sites for traditional healing were closed down in 1925, soon after the establishment of the Turkish republic. In 1926, as a part of the policies of closing down religious orders (tarikat), the dervish lodge that was hosting Mevlana’s tomb was transformed into the Museum of Asar-ı Atika, ‘the ancient monuments’.

While the ban on dervish orders delegitimizated the religious lineages (silsile) that have been traced back to Prophet Muhammed, the musealization of a functioning dervish lodge placed the religious power of the site in the past. To put it differently, as the name of the museum ‘Ancient Monuments’ suggests, musealizing Mevlana’s tomb proclaimed a barrier between the experienced time and the homogenous national time, in which secular sovereignty is defined through state’s power to hold the monopoly of regulating religious matters.

While the museum represents the everyday life of Sufi dervishes in the past tense by exhibiting items only belonging inside historical Sufi lodges, manifest the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government’s fantasies to bring the glory of the Ottoman Islamic past into the present via Mevlana’s heritage. The official program includes concerts, talks on spiritual love given by Muslim theologians in mosques, foundations and universities along with sema performances which is the bodily prayer requiring heavy concentration on breathing and whirling in which the semazen (whirling dervish) is manifesting what the God is revealing in his heart. In addition to these narrative frameworks offered by the museum and the official commemoration ceremonies, UNESCO promoted a de-Islamized version of Sufism, and Mevlana in particular, that has reached a wider audience in the USA and in Europe. Since the declaration of 2007 as a year of love and understanding, the Mevlana Year and the inclusion of sema, the Sufi bodily prayer, to the List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2008, the number of visitors of the Mevlana Museum has reached 2.5 million per year.

Inheriting Spiritual Love

The walls of this dervish lodge present a pretty unusual picture where the images of Alevi figures are hanging next to images of Mevlana, the seven chakras and energetic bodies.

On the small streets behind the Mevlana Museum, there are several houses operating as dervish lodges. While most of the Sufi dervish lodges have been spatially organized to accord gender-segregation, during the love-pilgrimage, the lodges host female and queer participants who do not belong to any order and do not conform with gender-segregation. Talks on spiritual love, the life of Mevlana and his teachings are presented both by male and female dervishes and are usually followed by ecstatic rituals of zikir and sema.

What we see in the photo is a group of musicians and one female semazen. A short while after I took this photograph, someone else, this time male, joined her doing semah, a movement ritual initially belonging to the Alevi tradition that has been systematically and violently discriminated in the Sunni majoritarian Turkey. Due to the systematic state violence enacted against Alevi citizens of Turkey, the Alevi religious iconography has been charged with heavy political tension. However, the walls of this dervish lodge present a pretty unusual picture where the images of Alevi figures are hanging next to images of Mevlana, the seven chakras and energetic bodies. Bendirs, the wooden framed drums that were used in this gathering, bore symbols of the third eye and the Tree of Life belonging to Jewish mystic tradition of Kabbalah.

Pilgrims inherit a particular energy of spiritual love that promotes the dissolution of the difference between the divine, human, and non-human love.

This gathering, where participants could join to the rituals, represents one of the numerous comings-together of the love-pilgrims to align with the energy of spiritual love. In the words of a female semazen, these gatherings are “platforms to share the channeled energies of love with the souls (can) who would like to merge with one-an-other.” (Interview, Konya 2019). The merging of the committed souls with spiritual love and with one another materializes in a state of trance. Whirling, joining to the repeatedly chanted prayers, watching the semazens, and letting the body moving in tune with the music people who gather in small rooms fall into trance. The trance ends with the Surah of El-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Quran. In this particular gathering, El-Fatiha was explained to those who had not mastered the Arabic language as the summary of the Quran and framed as a ritual of aura cleansing; the blessing of the energetic body that surrounds the physical body.

In this example where Quranic references merge with the language of energies and the symbols belonging to diverse religious and spiritual traditions come together illustrates that policies of heritagization indirectly promoted the formation of an eclectic spiritual terminology and set of practices without eclipsing the Islamic tradition that they historically emerged from. Through visits to the Mevlana Museum and participation in gatherings such as the one I briefly described above, pilgrims inherit a particular energy of spiritual love that promotes the dissolution of the difference between the divine, human and non-human love. Explained to me in several interviews in reference to Mevlana’s poem entitled Mingling, love is understood as a path of life where every existence mirrors every other.

Look: love mingles with lovers

See: spirit mingling with body

How long will you see life as “this” and “that”? “Good” and “bad”?

Look at how this and that are mingled

How long will you speak of “this world” and “that world”?

See this world

and that world

mingling.

This understanding is not favoring empathy, as many would assume. Omid Safi, a prominent Islam scholar specializing in Islamic mysticism conceptualizes the Sufi love as radical love, which is based on the idea of ultimate reflection. It invites the acceptance that everything, including those that annoy us the most, are reflecting parts of us that we haven’t met yet or we don’t prefer to acknowledge. In that sense, Mevlana’s idea of mingling and “being one” translates into seeing oneself in others. Different from empathy where the aim is to understand someone else, radical love suggests that there is no ultimate separation between one and others. Grounded on Sufi understandings, the spiritual terminology that is mobilized by the pilgrims suggests that the basic energy that motivates action is love. In this framing, the tomb of Mevlana, which is repeatedly framed by the love pilgrims as a point of high frequencies of love that operates as a portal opening into a higher consciousness. Aligning with higher frequencies of Mevlana’s love and distributing it to those around suggest a different model of inheritance than the one served to the preservation of Mevlevi orders. While the dervish order discipline involves a sense of community that is based on religious transmission through becoming part of an order discipline organized around masters who are believed to come from Melvana’s lineage (silsile), the process of receiving and manifesting the energy of love through gatherings I exemplified above suggests a model of inheritance based on shared capacity of sensing the energy of love.

Policies of heritagization opened up Mevlana and Sufi rituals to the appreciations of those outside of Islamic religious orders. However, destabilizing the given genealogies of inheritance as a “complex cultural technique of preservation” does not disentangle the notion of inheritance from responsibility. The scandal of the fraudulent English translations of Haafez (1315-1390), one of the most popular Sufi poets, is illustrative about the consequentiality of thinking about inheritance through sensing. Omid Safi revealed that the English translations of Haafez’s poems by Daniel Ladinsky are not the products of a translation work as we know. The English poems appeared to Ladinsky in a dream where he saw Haafez as a divine figure. What has been published under Haafez’s name in English were actually poems that Ladinsky wrote himself when he was channeling the spirit of Haafez. Ladinsky’s promotion of his poems under Haafez’ name is regarded by prominent scholars of religion and Muslim activists as an act of spiritual colonialism that erases the Islamic tradition from Haafez’ work.

It would not be a prophecy to claim that questions of ownership and spiritual appropriations will become a more visible issue with the increasingly digitalized world of rituals.

Processes of musealization and heritagization destabilized the master disciple relations and opened up possibilities of thinking about inheritance outside of geographically and historically bounded reference points. While communities are created around the experience of sensing energies of love without following the path offered by dervish orders, as we see in the example of Ladinsky’s translations, disruption in genealogies of inheritance fuels a set of questions of ownership and responsibility. How can we think about a model of inheritance that is politically informed about power relations and avoid reification of historically constructed ownership categories became an even more pressing question with the COVID-19 Pandemic. It would not be prophecy to claim that questions of ownership and spiritual appropriations will become a more visible issue with the increasingly digitalized world of rituals.