Central and Eastern Europe – known as “Bloodlands”, the area where Nazi and Stalin’s atrocities met, leaving behind many sites marked by mass killings – provide an obvious location for reflecting on human bones as material remnants of Europe’s past. Unearthing remains of victims of mass executions has been common in this part of Europe, and has stimulated increased international efforts to preserve and memorialize mass graves and killing sites. Human bones, however, feature as a more complex element of European memory-making and intergenerational process of making sense of who we are.

The prosperous Central European city of Wrocław, known as Breslau, does not often serve as a backdrop to the narratives of violence and death that frame the memory landscape of post-war Poland. This is in spite of massive escapes and deportations of German Jews to the extermination camps, and tens of thousands of lives lost during the siege of Breslau in 1945, when the city was turned to rubble. After all, not only was it a German city, but it also remained untouched by the war until early 1945. Yet, with nearly 70% of its population being replaced due to the post-war border shifts, Breslau experienced one of the most radical transformations in Europe’s history. It has become a very complex memoryscape and an ambivalent space of belonging, marked by the newcomers’ conflicted relationship to the remnants of the past they inherited, including graves and human bones – potential waste, unwanted and threatening with, to use Tony Judt’s phrase (1992), “too much memory”.

Gregor Thum (2005, translations mine) reflects on this population shift as a deeply disturbing experience for both sides: settlers displaced by the Soviet annexation of the Eastern part of Poland “came to a city completely strange to them, while the Germans had to leave a place that had become foreign to them.” The new inhabitants of Breslau were rootless and horrified by the city’s “strangeness”, its “repellent … Prussian-German appearance” (2005:40). They were determined to tame the foreign land, eradicate war traumas by changing street names, taking down statues, redesigning city spaces. In 1957, the communist government decided to start liquidation of pre-war German cemeteries: “Bulldozers were let into the necropolises … Cemeteries were turned into squares, without any exhumations” (Okólska in Maciejewska 2008).

While the liquidation of cemeteries and graves is a natural process, in Wrocław – due to the official politics and the indifference of the post-war inhabitants – it became an orchestrated operation of imposing oblivion. This and other acts of the refusal to accept testimonies of the past resulted in at least two generations of the city’s inhabitants for whom Wrocław was a place of “amputated memory”, absences and waste seen in all that was left behind and had to be disposed of.

The liquidation of cemeteries and graves became an orchestrated operation of imposing oblivion.

This “astonishing indifference” and “disgraceful barbarism”, as the authors of Cmentarze dawnego Wrocławia (2007) see the liquidation of Wrocław’s cemeteries, was finally challenged once the Iron Curtain collapsed in 1989. A long and complex process of sorting out the past began – the past erased from collective memory by the communist politics of “organized forgetting” (Wydra 2007) and deliberate attempts of de-Germanization (Thum 2005). Writers were first to publicly explore German history of the Western Borderlands; they were followed by artists and photographers interested in Wrocław’s past (e.g. Unknown City Portrait, The Germans did not come, Palimpsest), collectors of objects found in refuse dumps (Found. Saved), and enthusiasts looking for the remains of German tombstones in the city’s public spaces (Breslau Peeks from Under the Ground). With time, acknowledging Wrocław’s past has become in itself a form of the city’s collective identity.

Acknowledging Wrocław’s past has become in itself a form of the city’s collective identity.

It seems that the process of re-heritagisation, of taming the landscape and providing meaning and value to the inherited past visible in the material remnants of a foreign culture, was an inevitable response to the sense of unbelonging, a way of a coping with shallow roots. While the new settlers had to deal with the trauma of displacement and the fear that the Germans could come back, and were desperately removing any traces of the past, “tearing off the wallpapers because … the German breaths were preserved in them” (Kuszyk 2019), “[c]leaning and sweeping out this foreignness, this Germanness, which is peeping out from every corner” (Konopińska 1987:53), their children and grandchildren faced a different challenge. They realized that they neither belonged in their family’s eastern homeland, nor in the western lands, and that the myth of “the recovered territories” did not change the fact that they were growing up in the foreign land. The process of turning what could have been perceived as waste back into heritage, of weaving fragmented, discarded and redundant pieces into a coherent narrative, has thus become an integral component of their founding story.

However, this “astonishing indifference” has left its mark on the generations who, growing up in post-war Wrocław, would often discover the contentious heritages of the city’s past in the form of tombstones used as building material or recycled into wall bases, brick fences, paving slabs and street curbs. But sometimes, a more confronting trace of the past would emerge. Human bones – disarticulated, nameless and redundant – were discovered quite regularly in various parts of the city during roadworks, pipeworks, earthworks and other reconstructions of the urban space. Such discoveries evoked both anxiety and awe. They were of a “spectral quality” (Filippucci et al. 2013:6) and often left behind a sense of incompleteness and uncertainty that stayed for years with those who had made the discovery and those who witnessed it. They transformed into memories of materially experienced absences which still cause tensions in determining the identity of the place and its inhabitants.

Growing up in Wrocław in the 1980s, I had my own encounter with human bones in the middle of a new housing development, in the excavations made for heat pipes. It was challenging not only because of the sensitivity around human remains or their ambivalent object/subject status, but also because of the unexpectedness and peculiarity of the event. There was no usual architecture of death – no gravestones, crosses, names or dates, nothing to prepare me for this encounter. Human bones were obviously out of place, both in the context of the location where they were found and in a broader picture of my sense of home. There was no context in which the bones could be “assembled” (cf. Harries 2016) and made meaningful. So they were left as they were – abandoned, sometimes picked up by kids, briefly played with and discarded again. I do not know if they were ever collected and buried; at the time, they were a kind of surplus, waste, no longer meant to make meaning. But they were also a burden – something that could not be ignored or disposed of, as they “retain[ed] some spectral sense that they could be somebody” (Harries 2016).

The ambivalent agency of human bones, considered “uneasy subject/objects”, complicates the way we respond to and make sense of their materiality (Krmpotich et al. 2010:372), which is indicative of both an affective presence and absence (Filippucci et al. 2013; Domańska 2006a:341). Their materiality does not encourage a stable meaning, but signals excess as the unwanted remainder of something else, something once articulate and now turned into waste, “left over, neglected, surplus or insufficient to immediate requirements” (Harries 2016:1). This tension between affective presence and absence resonates also in a broader context – in the fact that the ambiguous materiality of human remains finds no support or justification in our narrative of home, it does not belong to our coherent, complete and convenient story, it exists as surplus that falls outside the “networks of consequence and significance” (Bissell 2009:112).

If, over the years, there has been a discomforting sense of concealments or absences in my and my fellow Vratislavians’ relationship with and understanding of ‘home’, the memory of this ghostly encounter, of disarticulate and nameless bones scattered in a construction site – could amplify it to a haunting sense of absence. However, at times, it could also bring a sort of relief. In fact, the emotive materiality of human bones, the ‘agency’ they exerted, can both increase the sense of absence and provide a means of dealing with it by establishing associations, connecting fragmented stories, filling in the void by providing temporary, even if fleeting, “comfortable proximity.” More starkly, this sense of relief is documented in research on the Rwandan genocide which revealed exhumers’ “inability to ‘stop looking’ at the remains” (Major, 2015:176).

The emotive materiality of human bones, the ‘agency’ they exerted, can establish associations, connect fragmented stories, fill in the void.

One of the ways to think about this affective presence/absence implied by human bones is to look at it though the concept of the non-absent past, defined by Domańska as “the past whose absence is manifest”:

By focusing on it we avoid the desire to presentify and represent the past, and instead we turn to a past that is somehow still present, that will not go away or, rather, that of which we cannot get rid ourselves. The non-absent past is the ambivalent and liminal space of “the uncanny”; it is a past that haunts like a phantom and therefore cannot be so easily controlled or subject to a finite interpretation. (2006a:346)

The memory of unearthed human bones, shared by many inhabitants of Wrocław, destabilizes the images of home and undermines the sense of the familiar, and threatens the stability of the collective identity “erected” together with the new city. It complicates the identity-making process not only because it is anchored in the tension between presence and absence, but also because it is a reminder of something that no longer confronts us in its materiality, but is hidden, removed, covered with new roads, parks and shops – a kind of waste.

The perception of human bones as waste encourages enquiry into the ways we deal with the past as well as the present. It directs our reflection towards disarticulate, nameless, redundant heritage, which is surplus to the requirements of our current, coherent narrative of the past, the place and ourselves. Applying such a lens enables us to look at ourselves not from the perspective of what we keep and value, but what we discard, both materially and mentally. Rejected as irrelevant and excessive to the current needs, the waste matter is a remainder of the past (cf. Harries 2016) and a reminder of our desire to forget and dispose of whatever lacks utility or does not fit neatly into our heritage treasure chest. Thinking of human remains as waste makes us uncomfortable, but also attentive to the ambiguous status of what constitutes both evidence and witness of the past, and critical of the present-absent dichotomy common in our thinking about the past (cf. Domańska 2006b).

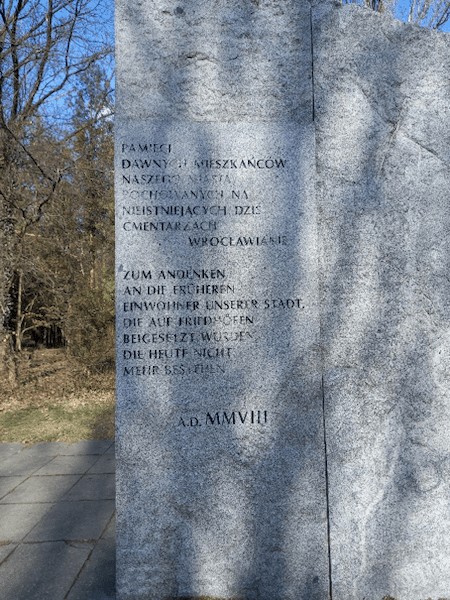

Mike Parker Pearson stresses that “dealing with the dead, recent and ancient, inevitably must serve the living” (1999:192). Today’s city has been encouraging conversation about the past. In 2008, in the Grabiszyński Park, the Monument of Common Memory (by Alojzy Gryt Tomasz Tomaszewski, Czesław Wesołowski) was unveiled in memory of the inhabitants of the pre-war city, whose graves had been destroyed and whose families were expelled. The idea was born when a pile of post-German tombstones taken from the Osobowice cemetery in the late 1980s was found in the fields near Wrocław – rubble and waste to be recycled. The city bought two hundred of the best-preserved slabs, which were partially inserted into the monument. This interesting monument was erected to directly address the city’s difficult past and preserve its material and immaterial heritage. It fosters remembering and reconciliation with the past at a collective level. But it does not resolve the challenges of the non-absent past; overcoming this persistent “inability to ‘stop looking’ at the remains” my generation has to deal with, requires more work. Working between memories of presences and absences we need to keep looking for ways of making sense of our experience and rendering bones articulate again.

Images, including the featured image: Monument of Common Memory, Wrocław. Photos by the author.

References

Bissell, D. “Inconsequential materialities: the movements of lost effects”, Space and Culture 12 (2009): 95-115.

Burak, M., H. Okólska, Cmentarze dawnego Wrocławia, Wrocław: Muzeum Architektury we Wrocławiu, 2007.

Domańska, E., “The Return to Things”, Archaeologia Polona 44 (2006a): 171-185. https://www.academia.edu/3134326/_The_Return_to_Things_Archaeologia_Polona_vol_44_2006_171_185

Domańska, E., “The Material Presence of the Past”, History and Theory, 45.3 (2006b): 337-348. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3874128.

Filippucci, P., J. Fontein, J. Harries, C. Krmpotich, “Encountering the Past: Unearthing Remnants of Humans in Archaeology and Anthropology,” Archaeology and Anthropology: Past, Present and Future, ed. D. Shankland, London: Berg, 2013. 197–218.

Harries, J., “Disarticulated Bones: Abandoned Human Remains and the Work of Reassociation”, Techniques & Culture 65-66 (2016). http://journals.openedition.org/tc/8185.

Judt, T., “The past is another country: myth and memory in postwar Europe”, Daedalus 121:4 (1992), 83-118. https://www.eastjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/judt-1992.pdf

Konopińska, J., Tamtem wrocławski rok [A Year of Wrocław], Wrocław, 1987.

Krmpotich, C., J. Fontein and J. Harries, “The substance of bones: the emotive materiality and affective presence of human remains”, Journal of Material Culture 15 (2010), 371–84.

Kuszyk, K., Poniemieckie, Czarne, 2019.

Maciejewska, B. „Pomnik Wspólnej Pamięci”, Gazeta Wyborcza 20 March 2008, https://wroclaw.wyborcza.pl/wroclaw/7,35771,5042599.html

Major, L., “Unearthing, untangling and re-articulating genocide corpses in Rwanda”, Critical African Studies, 7:2 (2015), 164-181. DOI: 10.1080/21681392.2015.1028206.

Parker Pearson, M. The Archaeology of Death and Burial, College Station, 1999.

Thum, G., Die Fremde Stadt. Breslau 1945, Verlag Wolf Jobst Siedler GmbH, 2003 [Polish translation, 2005].

Wydra, H., Communism and the Emergence of Democracy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.