In Niger one frequently hears that schools, specifically secondary schools, are haunted. Briefly put, this means that some schools are teeming with spirits, most of whom pose a threat to humans. The presence of spirits in these schools (and the threat they pose to female students, in particular) is a source of concern for parents and teachers, not to mention the girls themselves. The predicament was starkly captured in the testimony of a math teacher from Dogondoutchi, the small town where I have been doing fieldwork for over thirty years: “In our school, there is a date tree. There are seventy-one aljanu (spirits in Hausa) on that tree. They are presided by a female aljani (spirit in Hausa). Her name is Salamatou. [Spirits] go after humans because they are disturbed by them. When a town expands, aljanu have to move. Human activities bother them. They used to enjoy tranquillity in the bush, but now their trees are being cut.”

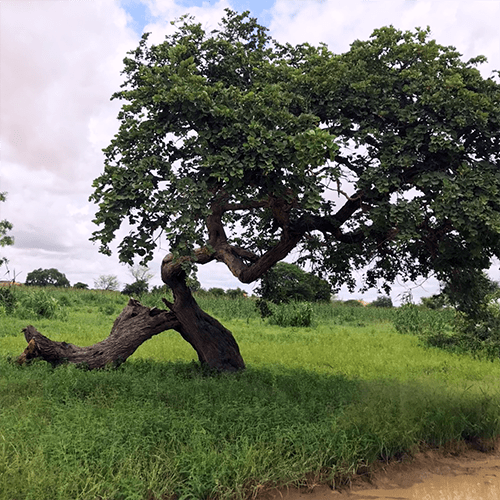

By cutting trees to make way for schools, the teacher implied, people broke the covenant established long ago with spirits. Now they suffered the consequences. The narrative is a familiar one in parts of Niger where the unravelling of people’s relationships with spirits turned what was once a blessing into a peril. Aljanu are known to dwell in caves, mounds, termite hills, ponds and bushy trees. As urban settlements, spurred by a demographic surge, encroached on the bush, many lost their homes. Some of them roam the roads that unfurl across the landscape, provoking accidents and prompting travellers to secure protective medicines before setting on trips. Others, averse to relinquish their status as genius loci (spirit of the place), linger over the very venues whose emergence contributed to their displacement. Initially they lay silent, undetected. Seeking an outlet for their grief, they eventually struck adolescent girls, who were made to suffer their suffering and demand justice for them.

In recent years the number of spiritual attacks in secondary schools has risen sharply. Possession in the classroom is often contagious. Moments after a girl is possessed, some of her classmates may be stricken too. These attacks are frequently blamed on the victims’ lack of modesty: bare heads and revealing clothes supposedly attract lustful spirits. Capitalizing on the panic elicited by the spectacle of female students in the throes of possession, Muslim preachers, who attribute the phenomenon to moral decline, urge women and girls to cover themselves and learn the Qur’an.

Aside from momentarily disrupting the tempo of educational life, the possession of schoolgirls opens a critical space for articulating the past as unfinished business.

When exorcisms are held to rid victims of their tormentors, a history of violence and disaffection emerges that unsettles the conventional event-aftermath narrative (Hunt 2016). How the irruption of wrathful spirits in classrooms and schoolyards unsettles the “pastness” of the past, forcing people to question the self-sufficiency of the present, is what interests me. The concept of afterlife highlights the inadequacy of conventional models of history for grasping local narratives of trance and iconoclasm, deforestation and nostalgia, haunting and education. By gesturing to “endings that are not over” (Gordon 2008:139), it offers a productive lens for escaping the predictability of straight temporality and entertaining the possibility that animacy extends beyond the human.

Haunting has frequently been used by social theorists as an allegorical device to capture the stubborn legacy of past epochs. Karl Marx wrote of past traditions weighing like a nightmare on the conscience of the living while Jacques Derrida discussed the spectre that disrupts our notion of linear time. In Niger, an overwhelmingly Muslim country, references to haunted places are not mere figures of speech. Haunting, for most Nigeriens, is a “natural” phenomenon. Haunted places are those places inhabited by spirits. Sometimes called the “hidden people,” spirits are invisible yet potent creatures. They may go about their lives quite oblivious to humans. Or they may demand attention, causing trouble if their requests are ignored (though they also protect people when provided for). To describe a school as haunted is to acknowledge the presence of the past—a past that calls upon the present with commanding resolve. It entails a recognition that the place is infested with spirits who may, at any time, seek redress for past wrongs and will not cease until they receive satisfactions.

When the landscape is saturated with the rage of spirits grieving for lost homes, it becomes unheimlich, posing a danger to humans.

Recall the date tree in the math teacher’s school. By stressing how crowded with occupants the tree was, the teacher suggested that local spirits had sought refuge on the only tree left standing when the school was built. Picture seventy-one spirits perched side by side on the pinnate leaves of a date tree! The vision conveys a definite eeriness, the sense of an ever-present threat literally hanging over the children who daily spill from classrooms into the schoolyard.

Many Muslims do not question the existence of spirits. Well-known passages of the Qur’an make mention of aljanu, bodiless creatures made of smokeless fire, who can take on a variety of appearances. For some people, the irruption of spirits on schoolgrounds is a bewildering experience, not easily reconciled with what they know to be true. A teacher from Niamey, Niger’s capital, admitted to being terrified by the possibility of spirits invading his classroom yet feeling helpless in the face of the problem because he wasn’t sure how to explain it to himself. He was not alone. Other people conceded they felt “epistemologically adrift” (Bubandt 2014:5) when discussing mass possessions. Spirits, Nils Bubandt (2017:G125) writes, “are never just ‘there.’” Paradoxically, because they are “both manifest and disembodied, present and absent,” they thrive in contexts of doubt (2017:G125). “These spirits’ attacks in schools. It’s an inexplicable phenomenon,” a school principal in Dogondoutchi told me after confronting an incident of mass possession. She wondered how best to help students who, having witnessed their entranced classmates wreak havoc in the school, refused to set foot in the establishment. “I don’t know about these things, I’m not from here,” she added. Caught between local officials’ insistence that the incident was due to mass hysteria (a common biomedical diagnosis) and the parents’ concern for their children’s safety, she wavered. For those who hover between endorsement and scepticism, spiritual attacks constitute something of an aporia—a nagging blind spot that undermines existential certainty as well as an “interminable experience” (Derrida 1993:16) for which there is no resolution.

In Niger spirits haunt even those who do not acknowledge their existence.

Spirits are not easily dislodged from the places they haunt. With the support of local authorities, headmasters may invite exorcists to rid schools of their lingering presence. One can never be sure the procedures are entirely successful, however. Obstinate, unyielding, deeply attached to places, spirits may withdraw momentarily only to return when least expected. A school principal turned on a taped recitation of Qur’anic verses in classrooms every evening to keep the spirits at bay. “The school where I teach has been haunted for many years,” a French teacher confessed. “We make sure students avoid certain places on the school grounds. We don’t want them to get hurt.” In this school, my interlocutor suggested, the past continued to resonate into the present in the form of a looming menace. Before possession attacks even took place, they were already anticipated as the recurring offshoots—the afterlives—of a violent, iconoclastic past.

In the past, elders recall, human settlements would neither take root nor thrive without spiritual support. If spirits depended on people for sustenance, human communities too owed their survival to the uncanny creatures. Recognition of this mutuality was sealed with the shedding of blood. In exchange for the blood of sacrifice, the spirits shielded people from various calamities, including drought, disease, and raiders. A community or clan’s relationship to spirits was encoded in prohibitions. People did not consume (or destroy) the plants, animals, and objects associated with the spirits whose protection they enjoyed. Hence, since trees were known to harbour spirits, one did not chop down a tree before securing its occupant’s approval. An ethic of conservation, rooted in people’s connection to the “more-than-human world” (Abram 1997), shaped the management of natural resources. Far from constituting the neutral backdrop against which human activity unfolded, the landscape was “a lived environment” (Ingold 2000). Trees served as chronotopes, emplotting relations between people and spirits while charging space with the movement of time. They were not forbidden—in the Durkheimian sense. After all they were sources of fuel, timber, and medicine. Rather than treat them as sacred, we might see them as “vibrant matter” (Bennett 2010) to account for the fuzziness between dweller and dwelling in people’s account of trees that “talk,” “scare them,” and “refuse to be cut.” Vibrancy also gestures to the lingering effects of past histories. Talking trees and axes bouncing back in the logger’s hand jolt people into awareness that, while spirits appear to have gone, their “seething presence” meddles with “taken-for-granted realities” (Gordon 2008:8).

The past century has witnessed waves of Islamic reform aimed at standardizing religious practices and purifying Islam from what Nigeriens call “animism” (spirit veneration). Muslim religious leaders destroyed spirit shrines, forbid sacrifices to the spirits, and discouraged reliance on bokaye, non-Muslim healers who treat spirit-caused afflictions.Claiming spirits were evil creatures in the service of Satan, they enjoined Muslim to shun them so as to avoid straying from God. Thus, spirits were forgotten, at least officially, and trees, which anchored spirits to particular places, turned into “things” (Luxereau and Roussel 1997), ostensibly ceasing to part of the cosmological fabric. Under this revisionist assault, the landscape that once pulsated with invisible forces became an inert backdrop against which human agency, with God’s support, could be deployed. People relied on Islam as a legal resource to warrant the clearing of land and the implementation of increasingly individualized forms of ownership (Cooper 2006). As some knowledges and ecologies diminished, new infrastructures emerged to keep pace with population growth.

Islamic iconoclasm transformed people’s relationship to their environment, yet it did not erase entirely the past. Today the landscape is filled with ghostly forms of past mutualities standing as reminders of what has been lost (trees, wildlife, and so on). If the past is experienced as a haunting—something that is lost, yet impossible to forget—it is also because most spirits have not gone away. When they make their presence known, it is often to threaten, frighten, and punish in short, to remind humans of their suffering presence. Stories are told of past trauma embedded in the landscape, lingering as residual affect: a school guardian dying after chopping down a neem, a girl terrorized after sitting under a tree, a man wounded by his axe while cutting a branch. Together these narratives paint a picture of the landscape as a place “energized by the violence of the past” (Aretxaga 1997).

When schoolgirls are tormented by spirits who refuse to let go of the past, it is ultimately the future that is at risk.

In Niger, the world’s least educated country, schools are seen as a critical driver of social mobility and girls are described as powerful agents upon whose shoulders Niger’s development rests (Masquelier n.d.). By keeping girls away from school for days, even months, spirit-related afflictions frequently bring their formal education to an end, thereby endangering the nation’s future. In her work on imperial pasts, Ann Stoler (2008:196) draws on the concept of ruination to highlight the protracted quality of damages to bodies, landscapes, dependencies. Ruination, which grapples with the multiple, lingering temporalities of loss, helps us frame spiritual attacks through the register of duration, experience, and anticipation. While evoked as a single event, the spirits’ expulsion from their homes is more adequately understood through its afterlife. Afterlives attend to the “agency of the no longer” (Fisher 2012:19) while gesturing to futures lost, experienced less as potentialities than as spectres—a site of what might have been. Here I have suggested that while the possession of adolescent schoolgirls brings into view the sheer force of the past, the harm spirits cause unfurls into the future, imperilling that which has yet to happen. As the “home” of spirits, some Nigerien schools are haunted as much by painful pasts as by imagined futures.

Bibliography

Abram, David. 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Penguin Random House.

Aretxaga, Begoña. 1997. Shattering Silence: Women, Nationalism, and Political Subjectivity in Northern Ireland. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bubandt, Nils. 2017. Haunted Geologies: spirits, Stones, and the Necropolitics of the Anthropocene. In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts of the Anthropocene, Anna Tsing et al. pp.G121-G141. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

_____. 2014. The Empty Seashell: Witchcraft and Doubt on an Indonesian Island. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Cooper, Barbara M. 2006. Evangelical Christians in the Muslim Sahel. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1993. Aporias. Trans. Thomas Dutoit. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fisher, Mark. 2012. What is Hauntology? Film Quarterly 66(1): 16-24.

Gordon, Avery F. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hunt, Nancy Rose. 2016. A Nervous State: Violence, Remedies, and Reverie in Colonial Congo. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. New York: Routledge.

Luxereau, Anne, and Bernard Roussel. 1997. Changements écologiques et sociaux au Niger: Des interactions étroites. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Masquelier, Adeline. N.d. “Girling” the Future in Niger: Education, the Girl Effect, and the Tyranny of Brighter Tomorrows. In African Futures. Clemens Greiner, Michael Bollig, and Steven Van Wolputte, eds. Leiden: Brill (under contract).

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2008. Imperial Debris: from Ruin to Ruination. Cultural Anthropology 23(2): 191-219.