Marie Gorm Aabo

Guided by Gut Feeling

Even before I started my fieldwork on sound, tinnitus, and soundscapes, I had a feeling that I needed to do experiments – sensory experiments that could help me study auditory impressions such as tinnitus. I started by focusing on the sense of hearing, but soon I felt the need to explore additional senses in my experiments. At some point, I started to look for the sounds, not just listen for sounds. In this short article, I will present for you one of my sensory experiments and how my gut feeling has guided me in experimenting with sensory phenomena.

It all began with taking photos of sounds. Whenever I heard a noise, I snapped a picture. The idea was to capture what I heard in a visual form. But capturing the sounds was not easy; sometimes the sound vanished before I could snap the photo. I started taking pictures of things that reminded me of sound, even if I could not hear them. It became a daily habit, and my phone was soon filled with hundreds of photos that I could “hear”. It was like having a visual archive of sounds!

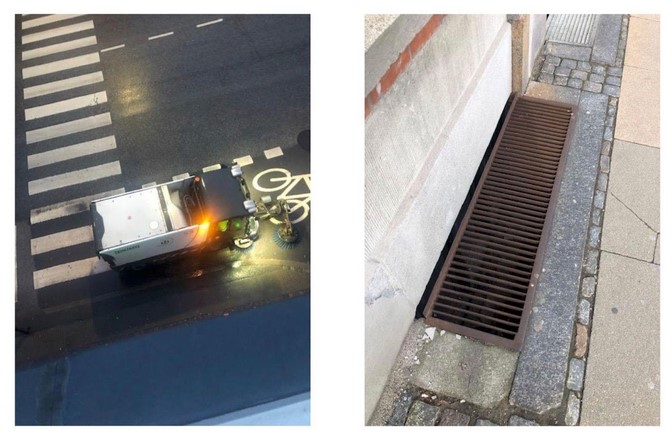

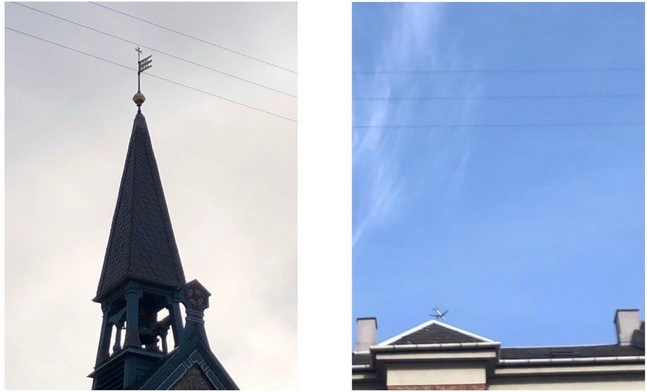

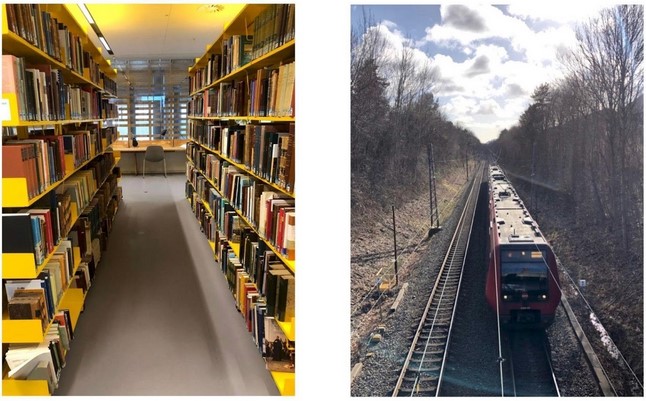

Inspired by Rita Irwin’s (2023) talk on “Visual Pairs as an A/r/tographical Strategy”, I sorted through all of my photos and paired those that seemed to fit together. This approach, grounded in art-based research, uses art to help us understand the things we cannot put into words, and to open our imagination toward the unimagined and the uncertain (Irwin et al. 2018). Pairing images was like connecting puzzle pieces. I looked for similarities: lines that matched, colors that resonated, and perspectives that echoed each other. It wasn’t a logical process; it was more about trusting my gut and following what felt exciting.

The more I worked on putting the photo pairs together, the more I recognized additional sensory impressions. My photos went beyond just hearing and sight; they resonated with other senses too. Consider the image pair #3: one person I showed the photo pair to perceived the absence of sound – the hushed reading room and the quiet train compartment. Or take image pair #1: I can sense the brisk morning breeze on the skin of my arms upon seeing it, evoking memories of the cycle path and the sound of the sweeping machine. For me, the pictures have an ability to engage emotions, my imagination, and even senses. Aligning them side by side fosters novel connections and sparks ideas.

Anthropological research reveals this deep interconnection of our senses, which is much more intricate than we tend to think (Howes 2011). In sensory science, synesthesia or intersensoriality emerges, for example, when you perceive audible aspects through visual media. Just as we experience food beyond taste, such as incorporating its tactile feel, photos, too, can extend beyond the visual realm, resonating audibly, and even tangibly. These reactions may stem from connotations or recollections such images evoke in our minds. Yet, this might be precisely how our gut feelings can be able to guide us into uncharted realms.

Following my gut feeling during experiments has allowed me to uncover hidden dimensions and deepen my understandings in the field.

I started relying on my gut feeling as a guide in my experiments, much like a compass needle or a dowsing rod, directing me towards new, uncharted territories. This helps me piece together the puzzle of my research, just as I assembled my photo pairs.

My visual experiments, my visual archive of sounds, and the photo pairs, along with other fieldwork experiments, may not have an immediate, explicit purpose. Although photographing and listening to the images has not provided groundbreaking insights into my fieldwork on tinnitus, the experiments steer me towards other approaches that can propel my work forward. While following my gut feeling can be risky or even biased, it has proven valuable for highlighting aspects of my fieldwork that might otherwise go unnoticed. Following my gut feeling during experiments has allowed me to uncover hidden dimensions and deepen my understandings in the field.

So, where has my gut feeling led me? Ultimately, my gut feeling has influenced the metaphors and approaches I employ, such as using images and other visual renditions to explore and communicate how my interlocuters experience tinnitus. It has guided and supported me in my research, enriching both my research process and outcomes. My gut feeling is not just instinct or intuition; it has also been an experience, a feeling that can be cultivated—sometimes referred to as “the ethnographic hunch” (Pink 2021). For me, it has been about pursuing what is most exciting, interesting, or inspiring, regardless of whether the experiments yield concrete results. The value lies in the direction it has led me, guiding both my fieldwork and analysis towards new and uncharted – but perhaps already gutfelt – territories.

References:

Irwin, Rita L. 2023. “Visual Pairs as an A/r/tographical Strategy” [talk]. March 15, Art-based Research, PhD course, Arts, Aarhus University.

Irwin, Rita. L., Natalie LeBlanc, Jee Y. Ryu and George Belliveau. 2018 “A/r/tography as Living Inquiry”, in Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by P. Leavy, pp. 37–53. New York: The Guilford Press.

Howes, David. 2011. “Cultural Synaesthesia: Neuropsychological versus Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Intersensoriality”. Intellectica. Revue de l’Association pour la Recherche Cognitive 55 (1): 139-157.

Pink, Sarah. 2021. “2. The Ethnographic Hunch”, in Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis, edited by Andrea Ballestero and Brit Ross Winthereik, pp. 30-40. New York, USA: Duke University Press.

Mónica Degen

Listen to your gut feelings

When students ask me what avenues of research they should follow or what personal decisions to take, I tend to answer: “What does your gut feeling say? You should listen to it”. Surprised, they look at me: “I should listen to my gut feelings?” Yes, listen to the yearnings, the whisperings, the palpable discomforts or desires, and inclinations inside yourself. Don’t be afraid to follow these and use them to guide your life and work.

As the piece by Hauge Kristensen in this collection highlights, the gut has received a lot of attention in recent years as medical scientists have discovered a connection between our intestines and the brain. These are linked by the enteric nervous system, “an extensive network of brain-like neurons and neurotransmitters wrapped in and around our gut” (Matthews 2020). This has led scientists to call the gut our “second brain” (Gershon 1999; for more details see: https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/a-gut-feeling-meet-your-second-brain/). According to recent medical research, this enteric nervous system is constantly in touch with our brain receptors via the vagus nerve and influences our decisions, mood, feelings, and overall well-being. While I am no medical expert, “gut feelings” have certainly informed most of my important life decisions. These gut feelings have also made me very aware of my own embodied self and the ways I make sense of feelings and atmospheres through the felt flesh, our sensory perceptions, and cognitive analysis. When seeing an image, walking into a room, or meeting a person, we “read” the image or room or person first viscerally and in response to our gut feelings. These gut feelings are not just biological, though: they also stem from one’s personal biography and prior experiences as well as the social and cultural worlds we inhabit. Of course, we don’t always express this verbally or openly as our rational mind filters, corroborates, and civilizes us. Everyone knows the feeling when something or someone is on “‘your wave-length” or “off”. You can feel it in the bottom of your stomach, in your gut – this can be as much a reaction to a space you enter, a visual image, a voice you hear, or a hand you shake. It raptures inside you and conveys what we call a “first impression”, often not in the form of a clear message but more like a constant murmuring.

Where are our gut feelings stemming from and how are they shaped by our individual life histories as well as social, political, and economic contexts? How can we use them creatively to possibly question and challenge mainstream ways of being, thinking, and researching?

Gut feelings link emotions, embodied perceptions, and cognitive thought as much recent medical research has shown; however, gut feelings have not been widely explored in much sensory research and are often regarded as unconscious responses that we have to situations. Yet, as several feminist writers have pointed out in their discussion of the affective turn, it is important to explore “the transindividual and relational aspects of feelings and fleshy visceral states of being/sensing” (Chadwick 2021:558; see also Ahmed 2014; 2017; Wilson 2015). Where are our gut feelings stemming from and how are they shaped by our individual life histories as well as social, political, and economic contexts? How can we use them creatively to possibly question and challenge mainstream ways of being, thinking, and researching? Indeed, as Ahmed (2017) has discussed, researchers should understand gut feelings as an intrinsic and important part of their knowledge production process, both in regard to writing and research. We need to accept them as a tool that might help us either understand existing patterns, ways of being and inequalities, or, used creatively, they can aid destabilizing or resist privileged accounts or methods. Thus, listening to your gut feelings can help to ground your choices, disclose what structures, ideas, or arguments you feel uncomfortable with, and open the doors to alternative arguments and research methodologies leading to new responses, unexpected links, and discovery.

References:

Ahmed, Sara. 2014. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chadwick, Rachelle. 2021. “On the Politics of Discomfort”. Feminist Theory 22(4): 556-574.

Gershon, Michael. 1999. “The Enteric Nervous System: A Second Brain”. Hospital Practice 34(7): 31-52.

Matthews, Robert. 2020. “From Microbiome to Mental Health: The Second Brain in your Gut”, BBC Science Focus, 8th Sept 2020, https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/a-gut-feeling-meet-your-second-brainhttps://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/a-gut-feeling-meet-your-second-brain, accessed 15/8/2023.

Wilson, Elizabeth. 2015. Gut Feminism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sanne Krogh Groth

Lead by my gut. Stepping back and stepping in.

In the summer of 2022, my research partner and I joined Indonesian friends who attended a jathilan event on the southern coast of the Indonesian island Java. Jathilan is an Indonesian trance ritual, where local dancers riding horses made of bamboo reeds go into trance by being possessed by spirits. The spirits are said to be attracted by the music played at these events – a style of music that mixes Javanese gamelan with Western electrified instruments – as well as by the smell of the food and incense offered to them. Depending on which spirit each dancer is possessed by (and not all dancers at an event are necessarily said to be possessed), there are several ways the dancers react to the trance. Most of them dance freely, seemingly in their own world, while others might chase the audience attending the performance; some behave like a specific animal, while others want to get whipped or insist they want to eat the husk of coconuts and even glass to demonstrate their invulnerability. When they are ready to do so, the dancers are helped out of the trance by the pawang, a type of shaman who conducts the ritual.

We had previously attended around ten jathilans when we went to the event in 2022, so the chaos and unpredictability of these performances were not new to us. On this particular afternoon, I even got the feeling that I had begun to slightly recognize the patterns of the performances: their basic story line, their melodic patterns, and their moments of sudden intensity, and its dramaturgical effects on the audience when the dancers entered the part of the performance where they went into trance. “Ok – now I’m starting to get it”, I remember thinking to myself, with professional distance and, I must admit, some degree of self-satisfaction. This is the first gut feeling I want to address: My feeling of comfort, recognizability, and surplus accompanying a fieldwork that by all means had been new to me. I felt a slight routine and my body and stomach were calm. I even put my phone down to enjoy the performance, without the extra layer of distance that accompanies our attempts to document the world in sound, video, and photos.

But then the whole event exploded with an intensity of eeriness and moved in a direction I had not anticipated; within a split second, my vibe of confidence changed. To the left of me, outside the performance space, two young boys among the audience were suddenly possessed. I believe some of the dancers had left the performance space and touched the boys, who suddenly acted like dogs – one of them with his eyes wide open, so that one could see the whites of his eyes. Most of the audience standing next to the boys became anxious and left the area around them, while a woman, probably the boys’ mother, burst out crying, very loudly, when she saw her son possessed. The boys’ bodies went rigid as they fell on all fours and began barking and growling like angry dogs. They had become the medium of the spirits.

The gut feeling that comfortably had guided my dramaturgic and aesthetic reflection was replaced with one that wanted me to be alert, to engage, and to act.

My own reaction to this was: “Hey! Someone get the pawang, quickly, so he can help them out of this!” This was beyond what I had the capacity for. My analytical distance and self-confidence had totally evaporated. My frozen body had goosebumps all over, and a tear came to my eye. Physically, I stepped back, but sensorially I had taken an unexpected and frightening step into the ritual and the new premises for the performance that suddenly entailed the possibility of spirits – not as analytical metaphors or ritual devices but as nonhuman persons. The secure gut feeling that was leading my analysis so comfortably was in a split second replaced with a gut feeling guided by impulses I had not experienced before. In that moment, I sensed the boys’ transformation into possessed mediums. I also might have been touched by the spirits myself. So, it seemed, was one of our Indonesian friends, who was just as disturbed as I was. He locked his eyes on me to ensure I was okay. After a few chaotic second, the situation calmed down. The pawang rushed to the boys with several helpers and quickly and calmly exorcised the spirits from the boys. The boys were escorted away, and the business-as-usual atmosphere of the jathilan performance resumed.

My bodily reaction was an invitation for me to sense a previously unknown mode of contemplation. The experience of the boys’ sudden trance affected me in such a way that my gut feeling changed drastically. The gut feeling that comfortably had guided my dramaturgic and aesthetic reflection was replaced with one that wanted me to be alert, to engage, and to act. My experience of the young boys’ possession was not guided by thoughts of analysis but became an impulse on how I could make sure that the pawang would come and help them out – only he would know how.

This experience has lingered with me. Ever since it happened, I have been wondering how I should analyze the sudden rift in reality that afternoon in which the guidance from my gut suddenly behaved in response to radically new premises. One might argue that my gut changed after being fed by another ontology – like spirits feed on the smell of food and incense to another. I was, for a moment, teleported from an ontology shaped by my Danish, culturally Christian background to the experience of an ontology where spirits play a significant role.

The co-presence of two different ontologies within my experience of one performance raises questions regarding methods of analysis, interpretation, and how to experience the world in the first place. For instance, it has made me rethink how to understand the term “media”. When the media (my phone) was put aside in one ontology, a spiritual media came to play in another. I am not suggesting a causal relationship between the two incidents, but argue for a sensory media anthropology that allows both to be present. This sensory media anthropology reflects upon central questions, such as: “Who controls the media?” and “What (or whom) is being mediated?”, encompassing the premise of more than one ontology. In the case of the jathilan event, the questions are ambiguous and multi-faceted; they lead to reflections on how this can be carried through in an aesthetic analysis, and how sensory media anthropology can be of support.

This article is a result of the research-project Java Futurism. Experimental Music and Sonic Activism in Indonesia conducted with Nils Bubandt (https://javafuturism.blogg.lu.se/)

Nanna Hauge Kristensen

An open-ended microbial journey

Barcelona, December 2000.

Giant disco balls spin in front of the city hall.

A group of people are protesting,

saying “No” to a dam in the Bio Bio River in Chile.

They play music.

The darkness is blue. It is the gloaming hour.

Tiny, rotating stars twinkle on the wall.

The moment touches me on the inside,

and a feeling arises.

A bodily knowing, maybe:

“I need to go to Chile”.

Quetzaltenango Guatemala, May 2001.

In the library of a Spanish language school, someone has left a book.

It is translated into Danish.

“An Unfinished Song”

by Joan Jara, the widow of Victor Jara.

She depicts the life of the Chilean singer songwriter.

His art. His activism.

Their love.

The military coup in 1973.

His death.

I read it,

and the same feeling arises.

An instinctive knowing, maybe:

“I need to go to Chile”.

A fateful union

This might be a detour, but in order to write about gut feeling, I want to go back in time. Approximately two billion years. To the dawn of time.

Imagine the Earth.

A drop in the galaxy,

75 % covered by water

and this is where life exists,

in the oceans.

Countless and single-celled.

A timeless swim.

Then suddenly,

by coincidence, maybe,

something occurs:

An archaeon engulfs a bacterium.

Two strangers enfold.

They continue to live

in symbiosis.

The first nucleated organism.

The beginning of multicellular life.

Now, everything moves fast.

Cells. Tissue. Organs.

New species. Odd kin.

A messy lineage,

with roots in the sea.

To become one with many

Symbiogenesis, “becoming by living together” is what the American biologist Lynn Margulis calls the merging of two distinct organisms. According to her, symbiogenesis is the primary force behind the origin of new species. Behind evolution. “Life did not take over the world by combat, but by networking”, she writes with Dorian Sagan (Margulis and Sagan 1997: 29).

And this is what we still do: we live in a state of symbiosis with trillions upon trillions of unicellular organisms. The majority of our human body consists of microbes – bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Our human cells take up less than fifty percent of what we are. This means that everyone of us is actually an ecological patchwork. An ecosystem. A multi-species collective. However, living in symbiosis does not equal living in harmony. Sometimes it can be a troubled and harmful affair. But this is not the point here. Rather, what is important, is that the microorganisms we coexist with form their own characteristic communities within us: skin, mouth, genitals, lungs. Each part of our body has its own collection of microbes – its own microbiome. The largest and most diverse collection being the microbiome in our gut.

And this is where we will go now. To the gut.

There seem to be more microbes in the darkness of a single human intestine than there are stars in the galaxy. Imagine it. This humid, dusky space – still rather unexplored. Research is only just now unlocking the profound role of the gut microbiome on human health.

What we do know is that the trillions of bacteria in our gut microbiome interact with both our immune-, digestive- and nervous system. Hidden in the intestinal walls we find the enteric nervous system. As Degen writes earlier in this collection, some researchers call it the second brain (Ruder 2017). A lot of decisions are made here – in our gut brain. And communication is taking place between our enteric nervous system and our central nervous system. This communication happens through the Vagus nerve, which travels from our lower brainstem to our intestines. Here, neurotransmitters carry information from the gut to the brain and vice versa. In other words, the Vagus nerve constitutes a gut-brain axis. A connection between our brain/mind and gut.

I wonder if we intuitively sensed this connection?

I mean… When we started using the expression gut feeling…

Did we have any idea about the deeper biological truth it conveys?

About the fact that our gut is literally providing us with information?

Santiago de Chile, autumn 2009

Iron crosses placed in lines, fractured. Nameless.

The bodies of the political prisoners who were killed after the military coup in 1973

rest in this part of the cemetery.

An elderly lady attends the graves.

“Your tip is my salary”, a sign says.

She was here when they brought the corpses, and buried them in piles.

And she was here when they unburied them.

I witness the exhumation of Victor Jara,

study art and documentary film, and go to the Atacama Desert in the North of Chile,

a microbial ecosystem in itself.

Here,

a vast sky, countless stars.

A drop in the galaxy.

A boundless thinking

A bacterial whisper? A political fascination? A timeless knowing? A gut feeling?

I am not sure what brought me to Chile. I only know that I was there, and that it left an imprint on me. Maybe with an extend I am not even aware of.

Every time we touch something, we receive and leave a microbial imprint. In the desert sand. On the kitchen table. On the skin of the people we hug. In this sense, our microbiome isn’t confined to our bodies. It perpetually reaches out into our environment as a living aura, as Ed Yong (2016) puts it.

If we take on a microbiological perspective, our sense of individuality gets blurred. Our skin constitutes a touch, not a boundary. Equally powerful dualisms such as Human/Nature, Mind/Body dissolve. This allows for more messy thinking. A symbiotic thinking.

The sociologist Mira Hird (2012) is developing what she calls a “microontology”. She seeks to push us to understand that “while bacteria are largely indifferent to our thriving, we are utterly dependent upon the teeming assemblages of dynamic microbes that make up and maintain both our corporeality and our biosphere” (Hird 2012: 69).

Having a microontology-awareness might install a humbleness within. A pause from our anthropocentric world view. It helps us recognize how we are odd patchworks of wet ancestors, microbes, and human tissue. Inseparable from our environment. Made up by invisible organisms. With that in mind, we are encouraged to depart from a confined definition of self. To drift into more open and entangled understandings of our being.

A bodily, instinctive knowing. A gut feeling, maybe.

What we can truly trust is that we are deeply interconnected – in concrete and mysterious ways – with our inner and outer worlds.

Santiago de Chile – Copenhagen, December 2009.

Christmas decorations in the streets, a burning sun,

summer in the southern hemisphere.

A farewell dinner with my chosen Chilean family

in a restaurant with a glowing light.

Then,

Copenhagen covered by snow.

This text is inspired by an audio piece I made in collaboration with Astrid Hald and Anne Neimann Clement for Medical Museion and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, published by Politiken: “Verden er i dig/ The World is in you”

Thank you to Michael Ulfstjerne for useful comments.

References:

Hird, Myra J. 2012. “Volatile Bodies, Volatile Earth: Towards an Ethic of Vulnerability”, in Why Do We Value Diversity? Biocultural Diversity in a Global Context, edited by Gary Martin, Diana Mincyte, and Ursula Münster, RCC Perspectives, no. 9, 67–71.

Margulis, Lynn and Sagan, Dorian. 1997. Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Microbial Evolution. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ruder, Deborah Bradley. 2017. “The Gut and the Brain”. On the Brain lecture series, Harvard Medical School. https://hms.harvard.edu/news-events/publications-archive/brain/gut-brain. Accessed August 24, 2024.

Yong, Ed. 2016. I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life. New York: Vintage Publishing.