The screen is dark, the music sombre. There are sounds of muffled voices and explosions. The dark screen breaks to reveal blue skies as the words “2011: A Suburb of Damascus, Syria” fade into the middle of the screen framed by white clouds. The camera pans down over a neighbourhood of beige buildings, interrupted by the piercing scream of a young girl.

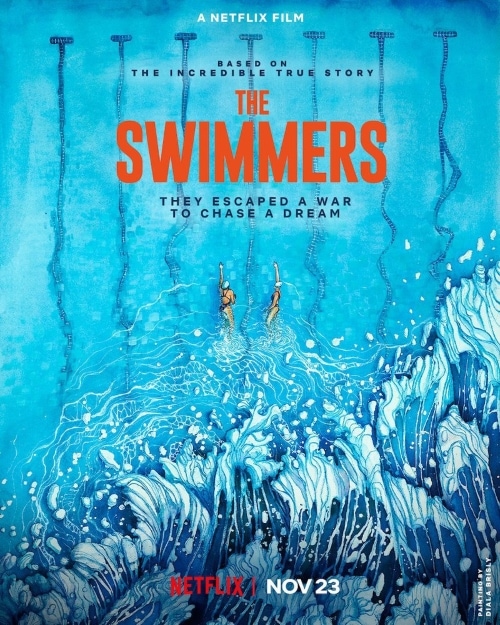

These are the clues dropped for the intended Western audience of the BAFTA-nominated Netflix film, The Swimmers, that tease an emotional beginning. The audience is led to expect what usually follows such clues in mainstream films set in the contemporary Arabic-speaking world: bombs falling, people running, and children screaming as the blue skies turn to a smoky yellow-grey. Viewers prepare to be plunged into despair, finally made to care about Syrian refugees by virtue of witnessing a re-enactment of their gratuitously violent victimisation.

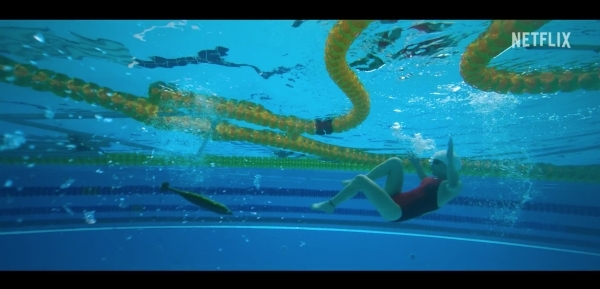

Except this is not what happens next. The camera continues to pan down to reveal a vibrant and packed neighbourhood swimming pool. The sombre music is jarringly interrupted by Colbie Caillat’s ‘Brighter Than the Sun’. The screams are those of playful children, the explosions created by cannonball leaps into the pool. The camera follows a rubber missile toy thrown into the pool and the sounds become again muffled. This underwater scene is at once foreboding and beautifully mysterious as the film’s title appears. It is clear that water—not the weapons, sand, or debris viewers may have expected in a story about Syria—will be the central motif through which our protagonists’ journeys will be told.

These first two minutes of The Swimmers set the tone for the film. Written by Sally El Hosaini, who also directs the film, and Jack Thorne, The Swimmers tells the story of real-life swimming sisters, Yusra and Sara Mardini, as they flee war in Syria, travel across the Aegean Sea in a lifeboat, and eventually claim asylum in Germany in 2015. Yusra, who had been training for the Olympics in Syria under the coaching of her father, continues to train in Berlin and competes in the 2016 Olympics with the Refugee Team.

Much more than a sports movie, The Swimmers, one of Netflix’s most-streamed films globally, is an Odyssean epic. With a running time of over two hours, the film notably spends a harrowing 12 minutes taking us along the Mardini sisters’ travel across the Aegean Sea in an overcrowded lifeboat. Those 12 minutes are just a fraction of the 3-hour swim Yusra and Sara underwent next to the lifeboat, pulling the sinking vessel to Greek shores.

While certainly dramatic, the film makes an effort to avoid exoticised imagery, using vibrant sounds, colours, and scenery to create the backdrop of a middle-class Syrian family as they experience their country’s descent into the confused chaos—and mundanity—of conflict. Around half of the dialogue is in Syrian Arabic—more than can be expected in mainstream films—and all scenes featuring the Mardini parents are exclusively in Arabic.

Still, Manal Issa, the actress who portrays Sara Mardini in the film, spoke out weeks after the film’s release about problematic aspects of the filmmaking, including the reproduction of orientalist cliches. One scene, for example, depicts Shada, a veiled Eritrean woman who meets the sisters during their journey, as remarking: “You don’t wear hijab. You swim. I’ve never met a girl like you before.” In this single line, Shada becomes a mouthpiece for the West’s projected desire for the emancipation of veiled Muslim women that anthropologist Lila Abu Lughod (2013) so eloquently described in her book Do Muslim Women Need Saving?. This desire becomes realised only thirty minutes later as Shada and a Sudanese woman unveil themselves so as not to arouse suspicion of their refugee status as they cross from Serbia into Hungary.

In her critique of the film, Issa also made several significant points regarding where the filmmakers could have been more intentional in narrating the Mardini sisters’ stories, especially considering the charges brought against Sara for her humanitarian work rescuing refugees making the same journey across the Aegean (some of the charges have since been dropped).

Dropped Life Jackets

Holding space for these critiques, I argue it is also important that we are not so quick to dismiss the film altogether, as many of the negative reviews have done. Beyond easy criticisms of the film’s sometimes cheesy English dialogue and its overuse of Sia ballads, The Swimmers still offers us subtle but crucial commentary not before captured in a mainstream Western depiction of forced displacement.

As audiences accompany Yusra and Sara on their journey from Syria to Germany, they witness the sisters experience how their identities as displaced Syrian women are felt as they move through different spaces, from the moment they decide to leave Syria to the minute Yusra wins her 100-metre butterfly heat in Rio. By the time Yusra considers competing for the Refugee Team in the 2016 Olympics, viewers have watched her wish to be identified as primarily Syrian become increasingly challenged by her status as a refugee. She asks her coach, “If you had the chance, would you want to compete because you were good enough or because people felt sorry for you?”

If Yusra, Sara, and the Refugee Team are to be the underdogs of a sports movie, it is because the global political structures have been designed this way. Just after the Olympics in Rio, I wrote an essay for Allegra Lab celebrating the inclusion of refugee athletes in the Olympics and also critiquing the reduction of their identities under the concept of a Refugee Nation. The language surrounding the Refugee Nation creates a false sense of inclusion, I argued, by adhering to the same nationalist model that excludes the stateless in the first place.

Forcibly displaced athletes like Yusra have been presented by the International Olympic Committee as belonging nowhere, without a home or a flag. They are represented by the Refugee Nation flag designed to look like a life jacket, which speaks loudly to their positioning as helpless victims who have slipped through the cracks between state borders. As Yusra and Sara reach Greek shores, their group tosses their life jackets onto piles of thousands of others with disdain. Here they reject the life jacket as a symbol of their victimhood, pointing instead to the international community’s failure to provide anything more.

I revisited my essay’s critique as I watched The Swimmers, which I believe attempts to challenge reductivist Western framings of refugee’s identities—even when recreating popular scenes of asylum seekers in Europe. In one of the film’s less dramatic scenes, Yusra, Sara, and their group from the lifeboat walk through picturesque alleys of the Greek island looking for food and water. Exhausted, barefoot, and dehydrated, they move as a group, and yet, this scene feels different from the dramatized images of racialised bodies on the move that are circulated by the media. While viewers are made to feel the violently physical toll of forced displacement, they have by this point in the film witnessed too much of the protagonists’ complex and flawed characters to reduce Yusra, Sara, and the others to mere bodies.

The Swimmers contextualises (albeit sometimes clumsily) the sisters’ displacement experience, illustrating how their pre-war aspirations changed at every critical decision-making moment. It demonstrates how experiences of conflict are gendered, exploring the blurred lines between benefactor and perpetrator in the actions of the Syrian soldiers[1] who sexually harass the sisters and the Hungarian smuggler who attempts to sexually assault Yusra. The film portrays meaningful solidarity through the friendships formed among the people with whom Yusra and Sara shared a lifeboat. And the English pop is balanced out by Arabic songs by a range of Arab artists like Syrian rapper Bu Kolthoum—a break from the indie sounds of Lebanese band Mashrou Leila so tirelessly replayed by Netflix Middle East productions aiming for an edgy Western appeal.

Add Refugees and Stir

While I believe it is important to appreciate what the film manages to do well in challenging stereotypical tellings of forced displacement, some of the positive reception around The Swimmers—like its critics—also misses its subtler messages by continuing to embrace reductivist tropes, centring on the ‘modernity’ and ‘liberalism’ of the film’s protagonists. El Hosaini herself wrote for The Guardian, “In the Mardini sisters I saw a chance to make heroes out of the type of modern, liberal Arab women who cinema usually ignores.” Such narratives ultimately reduce Yusra and Sara’s full character arcs to the gaze of “Western eyes” (Mohanty 1988): the sisters are young, pretty, middle class women who do not veil. And it gives us reason to believe some of the positive points about the film may have been unintentional.

The language used in the West to represent communities in the Global South is as important as the images, as Edward Said (1978) asserted in his seminal text Orientalism. The knowledge produced by Western linguistic and visual representations of the East has historically created ‘Others’ out of the Arabic-speaking world, framing them as exotic, backwards, and behind. These depictions not only marginalise the Other, they also pander to postcolonial projects that situate standards of progress and modernity in the West.

Feminist scholars argue that the problem of exclusion is not solved by simply including the excluded, but rather through structural change. For example, Sandra Harding (1991) critiqued ‘add women and stir’ approaches that aim to increase women’s economic participation by seeking to make patriarchal spaces more inclusive of women, ignoring the problematic design of these systems that function through exclusion. Following this line of thought, we then view the discourse around the Refugee Team as contributing to an ‘add refugees and stir’ approach that seeks to reincorporate the forcibly displaced within already prejudiced borders.

Likewise, vocabularies of modernity and liberalism regarding Arab women also further projects of exclusion around culture and deservingness. When such vocabularies are invoked in Western narratives in the name of ‘humanising’ those who are already Othered, this language essentially look for the ways that those Others are ‘like us’ in order to validate their existence and empathise with their stories.

If Yusra and Sara happened to look different—if they veiled or came from less privileged backgrounds—would the film still be celebrated for its representation of ‘modern, liberal Arab women’?

I propose instead celebrating the film’s protagonists for who they are rather than how they might appeal to the Western gaze, holding space instead for the complexity of identities in forced displacement. We should recognise their impossible Olympic feat—not just in a Rio swimming pool but also the Aegean Sea—while lamenting the structures that forced them to be so impossibly resilient.

What I believe the film manages to achieve—whether intentionally or accidentally—goes beyond proving that Arab refugee women are humans (isn’t everyone?) and have dreams (doesn’t everyone?). The Swimmers portrays how the Mardini sisters navigate the interwoven tensions between being displaced and Syrian, teenagers and professional swimmers, survivors and heroes, sisters and individuals. Yusra and Sara are more than the Western perception of them.

The language surrounding The Swimmers risks undermining the subtler but crucial contributions the film makes to the visual corpora of Western productions on forced displacement and the Arabic-speaking world. We should celebrate the film for bringing these stories to the Western attention, not their gaze.

Endnotes

[1] It is important to note that it is unclear who the Syrian soldiers represent in these scenes, a point that Syrian critics claim depoliticises and ‘distorts the reality’ of the Syrian conflict.

References

Abu Lughod, Lila. 2013. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Harding, Sandra. 1991. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1988. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review 30: 61-88.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Featured image: “The Swimmers” film poster as reimagined by artist Diala Brisly for Netflix. (Courtesy of Diala Brisly)