Mullah Yaqub appeared in the doorway of his Quranic school, and smiled when he saw me, shaking my hand firmly. He looked tall in his long dark-blue felted coat, wearing a black knitted cap on his head, with a silver beard, white and grey in places, and piercing light-blue eyes behind heavy eyelids.

We sat down in the little bare room that served as his office and he poured me a cup of tea. I told him that I had heard about the earthquake relief fundraising by Afghans in Istanbul, and that he was said to have organized it. He nodded and smiled, then stayed silent for an instant as if expecting another question. “In these moments, helping is not a choice, but indeed a moral duty,” he finally said. I agreed with him, but pointed out that not everyone could always heed a moral duty, there were material restrictions too.

“Take the path like virtuous men, and give a hand to the fallen as long as you are standing,” he said, smiled and added “Do you know the poet Sa’adi?”

The Quake

On February 6th 2023, at 4:17 in the morning, the earth shook in southern Turkey and northwestern Syria leading to widespread destruction on a scale unknown in decades. Later that same day, at 13:24 the earth shook again, toppling already damaged buildings and previously intact ones, burying thousands under rubbles.

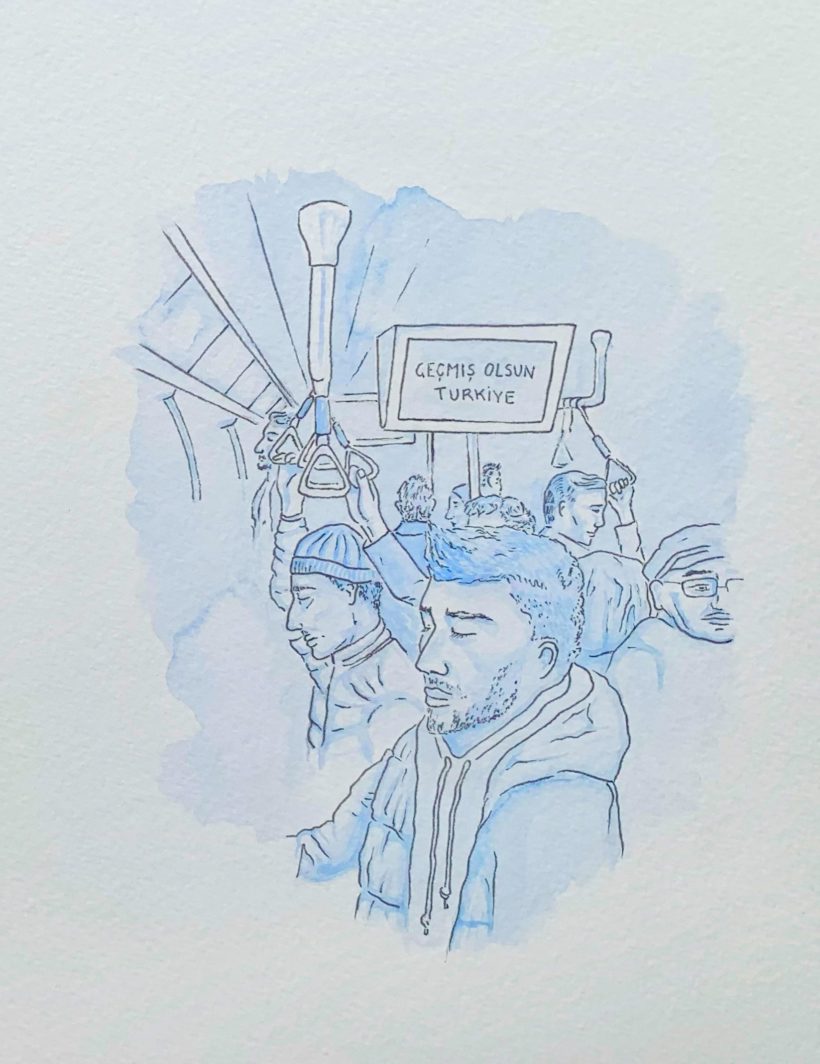

This was the most destructive earthquake in the history of the Turkish Republic. Together the two quakes are estimated to have led to the loss of over 55,000 lives and have left a further 1,5 million homeless, practically wiping out entire cities. The entire nation entered a period of mourning that affected all spheres of public life. Schools and universities ceased their teaching, theatres closed, music was no longer heard. Volunteers in their thousands searched for ways to reach the affected areas, while it felt like all eyes were riveted on the affected areas. Public displays of mourning and condolences were ubiquitous, displayed on billboards, metros and buses across the country.

The earthquake and the humanitarian situation that ensued, beyond being a seismic disaster, bears a deeply political component since the very day it struck. After over 20 years of taxes consecrated explicitly to earthquake disaster prevention and of norms and regulations concerning the construction of new buildings, the extent of the devastation and the belated state response has been perceived by many as an utter failure on the part of the ruling government by a large segment of the population—not least in the areas most severely affected by the quake.

Migration Contention

Equally contentious in political debates in the lead up to the election has been the question of migration. Turkey is the country that hosts the largest population of refugees worldwide, particularly from Syria and Afghanistan, 3,7 million according to the UNHCR. There is no consensus however on the number of Afghans dwelling in Turkey. Turkey plays a key role in the EU’s migration policy, as a large part of people hoping to reach the EU pass through Turkey before attempting to cross to Greece or Bulgaria. Particularly since 2016 and the signature of the ‘EU-Turkey deal’, the EU has been ‘outsourcing’ the task of border patrolling to Turkey in exchange for large sums of money, paving the path to border pushbacks, which, beyond frequently violating international law, have cost the lives of thousands in recent years (Reliefweb, 2022).

Across the political spectrum of Turkey, migration is a contentious topic. The largest opposition party has been vocal about the issue, arguing that the large number of migrants in the country is yet another aspect of the AKP’s failure in its 20 years of rule. It has promised to take a harsh stance on migration if it should come to power in May 2023, and to increase the ‘repatriations’ of migrants especially to Syria. The ruling AKP has also stepped up its deportation policy, particularly since June 2022—a date which most Afghans I spoke to remember as the beginning of far more frequent and violent arrests.

It is in this context that the Afghan population, among other migrant groups, have been struggling in their effort to remain in Istanbul, where most of them reside, and in Turkey at large. Legalisation of their stay through a residence permit or asylum in Turkey is extremely difficult and very rare for Afghans who have arrived since 2013, date at which the UNHCR suspended all third-country resettlements of Afghans. This means that most Afghans in Turkey today have no papers that could spare them deportation if apprehended by the police. Contrary to the widespread media and even academic portrayals of Turkey as a merely a country of transit for migrants on their way to Europe—a portrayal that perhaps speaks more about Eurocentric biases in these domains than of migrants’ own intents—many Afghans in Istanbul do not consider Europe the necessary next step in their migratory journey (İçduygu & Yükseker, 2010). Some Afghans have set up civil society organisations, ‘dernek’ in Turkish, which are recognised by the state, and which to some extent play a mediating role between the Afghan population and the state.

Efforts among Afghans to avoid apprehension and deportation do not limit themselves to legal statuses and documents, a domain to which they in any case have very limited access, but also goes through a variety of linguistic, and embodied practices, as well as drawing on material culture deployed in specific instances to navigate the gaze of onlookers onto them.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, among Afghans in Istanbul as in all other circles, conversations invariably revolved around the recent disaster. Five days after the quake, I was invited to the house of Esmatullah, a man of certain renown in Afghan circles, working as a sarāf—involved in the business of sending remittances back to Afghanistan or Iran for other Afghans in Turkey. Accompanied by his nephew Atiq, I crossed the Bosphorus by ferry and we made our way up to Esmatullah’s house in a quiet street of the Ataköy neighbourhood of Istanbul. It is there that I first found out about the Afghan fundraising for the earthquake relief efforts. Esmatullah greeted us as we entered, hugging us both. He was wearing his light grey pirāhan tunban (Afghan dress), and smiled widely as he let us in. He seated us in the kitchen-sitting room at the far end of the apartment. He brewed some green tea, as was his habit, and exchanged some news with Atiq in Uzbeki language before switching to Farsi for my benefit.

He sat down with the thermos kettle and spoke of the earthquake.

“We raised a lot of money,” he said, “almost 200 thousand lira.” I asked him how they had gone about it, and he said that he and some others had set up a WhatsApp group and had sent messages around.

“Inside of the Afghan community?” I asked.

“Of course—all Afghans,” he said, sitting very straight in his seat.

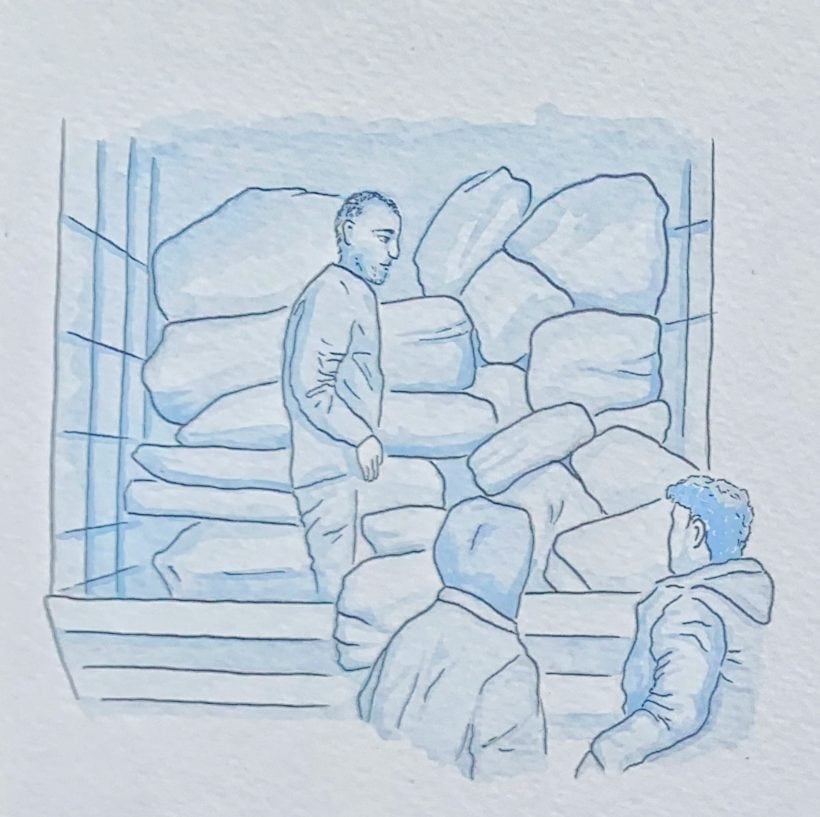

He explained that they had contacted the Göç Idaresi (the ‘Presidency of Migration Management’) and asked them what was needed in terms of materials, in the areas worst hit by the earthquake. They had received a list, including tents, tarps and blankets, which they had bought, and then organised cars to drive it all down to the affected areas.

Esmatullah pulled out his phone and showed us a picture of a tall man with grey hair, a beard, and a little knitted hat, standing before a van with its open sliding door revealing piles of wrapped goods, and another picture with a row of men standing before piled up bags, with the same bearded man among them.

I returned to Esmatullah’s house a week later, curious to find out more about the fundraising.

“Tell me more about the collection of money for the earthquake area,” I asked. “Have you heard anything more about it, did it all arrive?”

“Yes,” he nodded importantly. “It arrived. We must have collected over 2 lakh lira [two hundred thousand lira], maybe”.

I nodded, impressed. He carried on, explaining the importance of raising this money, and underlining the special bond between Turkey and Afghanistan, a point I had heard him make on several previous occasions.

“At the time of the founding of the Turkish republic, the first country to recognize Turkey was Afghanistan! We were the first to recognize it as a country. At the time Afghanistan was so far ahead, people from Europe would come and admire its infrastructures.”

“It is important that Afghans help today, at the time of the earthquake. Mardom khubi kona, digrān khubi mibina, mardom badi kona, badi mibina—People do good, the good will be seen, people do bad, the bad will be seen,” he declared.

He explained how help from those with the fewest means was the most valuable. “In Afghanistan, in Faryāb where we are from, people lined up, bringing all they had [following the earthquake in Turkey]. Some people brought chicken, sheep, or their jewellery, all to send to Turkey. You see, this is what having morals is. Here in Turkey, we had 1200 [Afghan] people who signed up to go to Hatay [one of the Turkish cities the most severely hit by the quake] to help. We spoke to the göç idaresi [the ‘Presidency of Migration Management’], and they said that they didn’t have the means to send all these people there. If they were already struggling to house the people who lost their homes, they could not house more people. Still 200 or 300 people went, workers, to help.”

“From Afghanistan, 270 people came to help the rescue efforts too,” he continued with an air of pride. “And 36 doctors came, good doctors, freshly trained. When they arrived, they had no means, I mean no SIM cards for instance. We, with the dernek, [civil society organization] provided this for them.”

Refugee in Times of Trouble

The border region between Turkey and Syria, the area most devastated by the earthquake, also hosts a substantial Syrian population—an estimated twelve percent in some areas. The highly politically charged themes of earthquake (mis)management and of migration collided tragically in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake as accusations of Syrians plundering collapsed houses widely circulated on social media platforms and in news reports. Investigations by researchers from GAR (Turkey’s migration research association) have shown that there is little evidence pointing to the fact that theft in the ruins was perpetrated particularly by Syrian refugees as alleged, but rather that these instances arose among many different groups having lost basic amenities along with their houses. Beyond this, it is suspected that organised criminal bands drove into the earthquake stricken area for theft on a bigger scale, though there is no evidence pointing to these having been organised by Syrians. In severely damaged cities like Kahramanmaraş, the Syrian refugee population is known to have actively joined the rescue effort. However, in the context of the earthquake, the term “refugee” has widely become associated with plunder and more generally, with an aggravating factor in an already highly strained environment.

Though the case I am describing is by no means unique, efforts to fundraise within migrant circles for earthquake relief have not figured in press coverage, or in public discourse. I was therefore all the more interested to speak to organisers of this fundraising initiative. I was put in contact with Hekmatullah who, I was told, had been crucial in organising this financial support.

We sat down at a table with comfortably padded seats on the third floor of a small café in the Üsküdar neighbourhood of Istanbul with a view over the Bosphorus. A group of four young women with pastel coloured headscarves sat at the table behind us, and two men in smart office clothing a little further down. Hekmatullah looked at me. I introduced myself again, and told him about my research and my interests—he jotted something down on his phone—finally asking him specifically about the earthquake relief efforts. How did it all come about?

“We saw what had happened and knew that we had to do something. This earthquake is not a personal matter; it is a matter that affects everyone. There is a man called Maula Yaqub, he has a madrasa [Quranic school] and heads a dernek, [civil society organization]. He called me on the 3rd day of the earthquake and said ‘Ustād,’—he calls me ustād [the Persian word for ‘teacher’] because I was a teacher for a while in Afghanistan—he said ‘Ustād, we need to do something together, to help.’ We made a list of contacts, and said that we were collecting money. Within 30 hours we had collected 132,000 lira.”

“Who were the people who donated?” I asked him.

“People we knew, we just sent a message around to our contacts.”

“And I guess a big part of them do not have a kimlik [Turkish ID card], right?”

He raised his eyebrows, “Ninety-five percent of them don’t. They have barely any money, and what they have they send to their families in Afghanistan.”

He thought about the numbers for an instant—was it 132 thousand or 134 thousand?—then checked his phone, confirmed 132 and returned to his story. “Next we went to the masul-e amniat-e göç idaresi, [the security office of the ‘Presidency of Migration Management’], and asked them what they needed—do you need clothes, jackets, hats, warm food, what do you need? They said you can either donate this money to AFAD [Turkey’s disaster management authority], or you can buy things yourself, and said that they mainly needed blankets.”

“We went to buy blankets,” he continued, “but they were all sold out. So we went to Zeytinburnu [a neighbourhood of Istanbul home to many Afghans], and walked from place to place, and collected blankets, and diapers for children. We went back to the göç idaresi [the ‘Presidency of Migration Management’] with all of the supplies and they organized the car, to transport this to the earthquake zone.”

Hekmatullah’s gaze drifted out of the window and over the sea to the European side of Istanbul. “It’s a human duty, in the end,” he said as he returned to this side, “I don’t know what their religion is, I did not ask you what your religion is, because it doesn’t matter, they have a right to help as much as anyone else, right?”

Several points of interest arise from these discussions, which merit highlighting. “This earthquake is not a personal matter; it is a matter that affects everyone.” The manner in which Hekmatullah explains the impetus to help, is one which universalizes this duty—it is underlined as a moral or civic duty for all, not as an act of generosity that merits gratitude. Described as a collective duty, it hints at an instance of bridging an otherwise firm social divide. Particularly in the context of the vociferous media reporting and social media commentary of migrant presence as an active hindrance to disaster relief, this act of fundraising seems to defy the crassly drawn borders between inside community and ‘foreign body’—a divide, which Afghans materialises itself in innumerable contexts on a daily basis, from exploitative labour conditions, to access to medical care, but also wheedles itself into the intimacy of interpersonal relations.

The social divide between the national community and ‘foreigners’ obviously does not evaporate despite this bridging act—particularly in this tense pre-election. However, statements like that of Esmatullah attempt to mediate this tension between ‘local’ and ‘other’ by framing it as a link between national communities highlighting a historical solidarity, rather than a question of migration—one more chapter in a historic bond in a geopolitical relationship.

Hekmatullah’s explanation however highlights a more universal impetus to help. He actively refutes a sectarian reading of this Afghan support, by underlining the irrelevance of my religious affiliation or that of the receivers of this aid. Similarly to Maula Yaqub, he mobilises a language of rights and obligations that are, in his view, universal. How can we understand this universal call to solidarity? Anthropological studies of humanitarianisms invite us to think of the variety of spheres in which solidarity is conceived to take place (Mittermaier, 2014). Studies of vernacular and Muslim humanitarianism(s) have critically reflected on the the widespread association of (good) humanitarianism as necessarily associated with principles such as impartiality, secularism, and apolitical action (McNevin & Missbach, 2018; McNevin, 2020). These perspectives choose to instead focus on the diversity of ontologies that inform humanitarian action (Iqbal, 2022). They bring to light the fact that aid is not always conceived as an action that remains within the confines of a social interaction between two actors—a donor and a receiver—in a supposedly apolitical interaction. This conceptual and analytical shift also permits to look at this action on the part of Afghans in Turkey in a way that does not attempt to dissociate the political, performative or affective character of aid from a ‘truer essence’ which would be that of altruistic and non-utilitarian generosity, and rather understand this action within the highly politicized context of Afghan lives in Turkey.

In this way, the choice of going through the Göç İdaresi for their financial support becomes all the more significant. The Göç İdaresi, officially translated as the “Presidency of Migration Management” is the state’s office in charge of migration, which, beyond deciding on the attribution of residence permits and asylum protection is itself in charge of the detention facilities and the subsequent deportation of migrants—it is thus not related to disaster management. Afghans being one of the most frequently deported national groups, approaching the authority in charge of this very deportation strikes me as a meaningful and symbolic act. Far from insinuating a utilitarian motivation for this action, I would argue that it is a moment in which this community’s understanding of the political nature of their presence in Turkey and the political nature of disaster relief work crystallises itself into an action. In an instance in which visibility and invisibility of the community can mean the difference between deportation or continued presence, choosing to act in this precise moment, and selecting this institution, is a political and performative act—one which holds a potential to momentarily challenge the relation between this group and the wider Turkish society by way of its gate-keeping institution.

The act of fundraising in this particular context cannot be said to hold a fixed or singular meaning. It does not change the material and legal condition of those who participated, nor does it set out to do so. The performative character of this action is perhaps less oriented towards the potential external onlookers—who in any case were few, as the action remained unpublished—than to the community itself. It momentarily challenges the boundary between migrants and non-migrants, and thereby to how people may relate to the space, which they inhabit, a space in which legal means are used to make migrants feel temporary and deportable.

Conclusion

In a context where legal means to ensure an enduring stay are almost entirely out of reach, other forms of assertion become all the more important. This case of a group of young Afghan workers, raising money for a national emergency is one of a number of material, discursive and embodied practices through which the ‘community’ draws in an effort to negotiate its relationship to its social and political environment. By including themselves discursively among those who are in the universal moral obligation to attend to the earthquake’s victim’s rights to help, Afghan ‘migrants’ include themselves within a certain civic contract and question the citizen non-citizen divide .

I would like to suggest that the way to understand this action of post-earthquake solidarity on the part of a group of Afghans should be located in wider practices of giving in Afghan diasporic networks. It should be conceived as less of a unidirectional instance of giving—as charity is often conceived—but rather as part of a network of solidarity whose importance materializes time and time again in the instances in which the role of helper and helped have been known to rapidly reverse. Far from pointing to a culturally essentialist understanding of generosity as a timeless essence in Afghan practices, I suggest understanding this act of solidarity as an instance of complex deliberation not least emanating from a context of over forty years of violent conflict and displacement.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Eda Sevinin for her help and support in writing this article, and the long conversations that preceded it, which inspired me to write about this topic. I would furthermore like to thank Dr. Didem Danış for sharing her insight about the earthquake and the wider political context in which it took place, as well as for all her support, which made my fieldwork in Turkey possible. I am also grateful to the IHEID and Galatasaray University for the affiliation and the support they have offered me. I also thank the Afghan community, especially Esmatullah, Hekmatullah and Maula Yaqub for their insight and trust and for sharing their stories with me. I would like to thank Allegra Lab for the opportunity to publish this case, and for their constructive comment on my work. Finally I would like to thank Dr. Alessandro Monsutti for his constant support, advice and encouragement as a PHD supervisor.

Bibliography

Aksel, Damla B. & Didem Danış (2014) “Diverse Facets of Europeanization at the Iraqi-Turkish Border” in Nurcan Özgür Baklacıoğlu and Yeşim Özer (Eds.) Migration, Asylum and Refugees in Turkey: Studies in the Control of Population at the Southeastern Borders of the EU, Edwin Mellen Press.

Butler, J. (1993) Bodies that Matter. Routledge.

Daily Sabah (2022) CHP Chair Kılıçdaroğlu vows to send all Syrians home from Syria. Accessed 20.03.2023

Göç İdaresi (2023) Düzensiz Göç & Uluslararası Koruma Accessed 20.03.2023 &

Le Chêne, E. (2019). La fabrique de l’asile sans le droit à l’asile. La gestion différentielle des exilés « non européens » en Turqui e. Sociétés Politiques Comparées. Revue Européenne d’Analyse Des Sociétés Politiques.

Tolay, J. (2012) Turkey’s “Critical Europeanization”: Evidence from Turkey’s Immigration Policies. In Elitok, S. P., & Straubhaar, T. (2012). Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities. Hamburg University Press.

İçduygu, Ahmet & Damla B. Aksel (2014) “Negotiating Readmission Agreement between the EU and Turkey: Two-to-Tango”, European Journal of Migration and Law, 16(3). SSCI Indexed Journal.

İçduygu, A., & Yükseker, D. (2010). Rethinking Transit Migration in Turkey : Reality and Representation in the Creation of a Migratory Phenomenon. Population, Space and Place, 18, 441–456.

Iqbal, B. K. (2022). Economy of Tribulation: Translating Humanitarianism for an Islamic Counterpublic. Muslim World, 112(1), 33–56.

McNevin, A. (2020) Refugees and First Nations Sovreignty. Presentation at the Mellon Sawyer Seminars Series.

Mcnevin, A., & Missbach, A. (2018). Hospitality as a horizon of aspiration (or, what the international refugee regime can learn from Acehnese fishermen). Journal of Refugee Studies, 31(3), 292–313.

Mittermaier, A. (2014). Beyond compassion : Islamic voluntarism in Egypt Tto Cairo to study. American Ethnologist, 41(3), 518–531.

Reliefweb (2022) EU-Turkey Statement: Six years of undermining refugee protection. Accessed: 20.03.2023.

Sabah (2021) Isa Tatli. Afganistanlı Dernekler Birliği kapılarını SABAH’a açtı. Accessed 20.03.2023.

Tolay, J. (2012) Turkey’s “Critical Europeanization”: Evidence from Turkey’s Immigration Policies. In Elitok, S. P., & Straubhaar, T. (2012). Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities. Hamburg University Press.

UNHCR (2023) Refugee Data Finder. Accessed 20.03.2023

Featured image by Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, courtesy of Flickr.com.