‘Is it ethical to write something ‘interesting’ about a massacre as the massacre is unfolding?’ I keep asking myself. ‘Is this not a form of exploiting the dead to produce literature out of the decaying bodies?’. I start thinking of Levi-Strauss’ analysis of the trickster and the carrion-eater as mediators between life and death (in The Story of Asdiwal).

‘In any case’ I say to myself ‘whether it is ethical or not, there is still an even more, practically speaking, fundamental question. ‘Is it possible to write (full stop) as the massacre is unfolding?’ I certainly am finding it hard to do so.

I was asked about the same time by Julie Billaud (for Allegra) and Fadi Bardawil (for Megaphone), if I could write something about Gaza. My overwhelming feeling was one of sadness about what is happening but also of futility and uselessness. I just couldn’t bring myself to write. Some of the same ideas I struggled with when I wrote ‘The haunting figure of the useless academic: critical thinking in coronavirus time’ (European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 23, no. 4) were blocking my writing horizon. ‘Massacre time’ was even more prone than ‘Coronavirus time’ in instilling in an intellectual a sense of being the last one needed around the place. Who wants to listen to intellectual pontification while burying the dead?

There was also a sense of futility that comes from intellectual encounters with the déjà vu. I listen to some of the arguments floating around in relation to Hamas’ massacre of Israeli civilians. Many have been argued before in relation to suicide bombers. What is the difference between terrorism and terrorists? (I think Hamas’ attack was an act of terrorism, but I don’t think that makes them a terrorist organisation. Terrorism is a type of political violence. Israel also engages in terrorism. It doesn’t make it a terrorist organisation either). What is the difference between understanding political violence and condoning it? I once coined a word in relation to suicide bombers: exighophobia, the fear of socio-historical explanation. Plenty of it circulating now. If logical arguments defeated illogical politics we wouldn’t be where we are now. and I am not only talking about Middle East politics. I am talking about the rise and rise again of extreme right politics, racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.

I am thinking many things but not many are worthy of writing. Every now and then something that does not make one repeat the same arguments ad nauseum emerges and triggers new reflections. I am having a zoom conversation with my friend Abbas El Zein (he’s in Australia, I am in Germany) and I am talking about this. He makes an interesting remark which I found worth thinking about: Hamas’ attack has more in it that is reminiscent of the early high jacking of planes by the PLO. In the sense of the attack being a way of asserting the existence of the Palestinian people and of the Palestinian cause in the face of a reality (pacification between Arab regimes and Israel) that was unfolding as if they and their rights and their suffering did not exist. But that’s as far as the similarities go. The operational sophistication, the strategic intentions and the atrociously different degree and scale of the massacre of civilians take us somewhere else. Indeed, it has taken us somewhere else. And another interesting question here given the entanglement of Hamas and Iranian politics: is anti-colonial resistance possible in an age that seems more over-determined by geopolitical machination than ever?

Israel’s revenge raid into Gaza had all the characteristics of the colonial punitive expedition.

I hear some right-wing British journalist telling Piers Morgan that ‘the people of Gaza are not exactly peacenicks’. It is always interesting how some westerners lament the fact that the colonised are just too vulgar, violent and unsophisticated for their refined taste. As if years and years of colonial brutality ought to produce a nice liberal cosmopolitan culture. There are many Palestinians in their twenties, thirties and forties, raised in Gaza, who have grown up being continuously bombed, imprisoned and humiliated by the Israelis, losing a relative here, and a friend there, a limb here and a bit of their soul there, on a yearly and sometimes monthly basis. Is it so hard to imagine why they did not have in them a capacity to mourn the victims of Hamas’ murders on the 7th of October?

There are of course those of us who, despite our opposition to the Zionist ethno-nationalist project, from the comfort of our social and geographic location, and because of our plural attachments, had it in us to mourn the victims of Hamas’ murders. Still, we found ourselves unable to share our mourning with the way they were mourned by the Israelis and their Western allies. For, as the Israeli massacre of Palestinians began to quickly overshadow Hamas’ massacre in its scale and in its racist de-valorisation of those being killed, it became clear that this was no ordinary mourning of the dead. This was a supremacist mourning: the world was invited to accept that, unlike Palestinians who are murdered all the time, the murdered Israelis were special. They were superior dead people who needed to be revenged in a way that reminds everyone, but particularly the killers, of how superior they were. Anything less was “anti-Semitism.”

For anyone who knows their colonial history, it was very clear that Israel’s revenge raid into Gaza had all the characteristics of the colonial punitive expedition. Indeed, it followed a well-established script, which structure has been replicated in every colonised space and by every colonial power without exception: The colonisers invade, take over a territory, kick the natives out of their lands and homes and destroy their livelihood and their modes of life. Then, they slowly drive away, or round up, the colonised and make them live in unbearable conditions. When the colonised get to the point where, as Fanon put it, ‘they cannot breathe’, they revolt, attack and kill some of the colonisers – sometimes in truly horrific fashion. Here the colonisers declare themselves outraged as if there was no reason at all behind such barbaric murderous behaviour. They assert their ‘right to defend themselves’ and launch a ‘punitive expedition’. The punitive expedition is always extra-judiciary, it uses the legal language of rights but it seeks revenge and aims to kill as many natives as possible in a totally illegal fashion. The colonisers use the latest killing technologies against a far less militarily capable force and engage in a wholescale genocidal massacre aimed at teaching the natives a lesson ‘they will never forget’. That is how colonisers have always mourned their very special dead ones. The US, the French and the British are experts in the field. They’re all supposed to have atoned for their past colonialisms but happily joined the transnational coalition encouraging the unfolding of this one. Australian colonial history is full of such genocidal punitive massacres. But somehow the Australian government couldn’t see the similarity when they declared their full support for Israel’s right to defend itself. Go figure. German colonial history in Africa provides us with notable examples of such genocidal punitive massacres. But the German government couldn’t remember their history either. They use remembering one atrocity they have committed to block remembering another.

I am thinking all this but I hadn’t written it in a linear narrative until now. I was doing it in fragments. A talk in Stockholm on ruination. Some social media posts. I am re-assembling them as I am writing at this very moment.

I was reflecting on this inability to write when Fadi Bardawil contacts me again to check if I have managed to write something for him. He clearly understands the difficulty. We don’t talk about it much. I tell him I am trying. But I am telling myself that there was something more than ‘the horrors of the massacre, not wanting to be a carrion eater, and all that’ that was stopping me from writing. I note that in periods of intense fighting during the Lebanese civil war I sometimes had problems finishing sentences. During this war, however, I am having problems starting them. Every sentence we begin to write is full of hope. If nothing else, it takes time to finish a sentence, and when we utter the first word we are at the very least hopeful that we’ll live long enough to finish it. To start sentences even when you don’t finish them is a sign of hope, even if not finishing them means your hope has been thwarted midway through. But not to have it in you to start sentences is a sign of depression.

I note that in periods of intense fighting during the Lebanese civil war I sometimes had problems finishing sentences.

After talking to Fadi, a past incident came to my mind in the middle of the night. For many years now I have come to accept that, while I rarely have a problem going to sleep, I am unable to sleep for longer than four or five hours at a time. This means that I usually wake up around 2.00 or 3.00 am and I am in this situation where I can neither go back to sleep nor get up and do something. So, I often spend an hour or two where I am not sure if I am dreaming or remembering things. And that is when this incident came back to me. Whether a dream or a reminiscence, I felt it was important that it came to my mind when it did.

The incident had to do with something that happened in the Lebanese village of Mehj. It is one of the villages where some twenty years ago I began my fieldwork for my book The Diasporic Condition. Mehj is not its real name but that’s how it figures in my ethnography– and now that I remember, Fadi, as a young student, accompanied me to this village at that time, so maybe that also helped triggering it. But well before that time, the village is a place dear to my memory. In the early 1970s, a school friend had an old-style house with particularly acoustic friendly rooms where he had set up the best of the best of sound equipment, and where we drank all kind of things and smoked all kind of things and listened to all kind of things (Frank Zappa, Mahavishnu, Teleman and Bartok were all time favourites).

After I migrated to Australia, whenever I went back to Lebanon, going to Mehj was like a ritual that involved a reunion with friends and a reunion with the space. In my case this was more significant than the usual diasporic return pilgrimage. It was so because at the time I was transitioning from adopting an uncritically inherited right-wing Christian Maronite politics to becoming a left-wing Australian. The space made up of my old friends (who were mainly Maronites) and the village house acquired a particular importance to me. It was the only place that I related to since my teenage years where I could be myself, and where I didn’t have to hide my changing world views as I had to do around my relatives and parental entourage.

The incident in question happened in the 1981: I had just returned to Lebanon and was with my friends listening to some music and smoking some hash when some friends of our friend, whom I’ve not met before, joined us. At first it was much the same, endlessly talking about music, exchanging jokes and anecdotes, but soon the conversation moved to politics and one of the newly-arrived people started making a classical Maronite argument: the Palestinians want to take over Lebanon and make it their own country as a substitute to Palestine and they want to kick ‘us’ out of Lebanon.

‘This is just nonsense’ I couldn’t help myself from saying.

He turned to me as if I had just denied the most fundamental truth that was at the basis of his existence and very quickly became quite aggressive: ‘Fuck off right, I don’t know who you are but fuck off. We don’t need to hear this bullshit here’ he said.

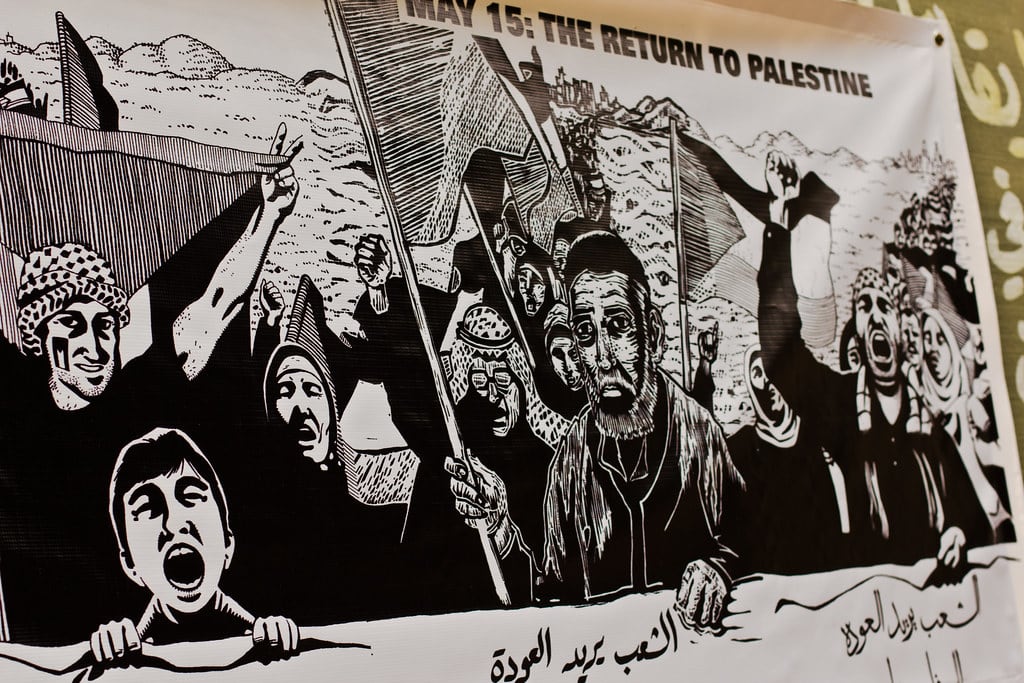

I wasn’t intimidated by his initial agressiveness. I continued ‘Well. I am interested. What evidence you have that the Palestinians want Lebanon as a substitute to Palestine. Look at their school books, why would they still be teaching their kids that the most important thing on earth is returning to Palestine if what you say is true?’ He looked at me as if I was really something vile. ‘Have you got any evidence other than the fact that you believe this to be true?’ I insisted.

As I finished, the guy got up and said in a seriously threatening tone.: ‘You want proof. I’ll go to my car and get my gun. Will that be proof enough?’

This time I was scared. But I gathered enough courage to say ‘forget it. I don’t do gun things. I prefer to just talk’. It was a rude awakening: living in Australia as a radicalised student and spending nights debating and arguing about Marxism, imperialism and world politics, had lulled me into thinking that politics was a long intellectual debate, involving shouting matches at the worst. That evening, I realised there and then that I was just a silly Australian student. I was not, but frankly, I was glad I was not, as I didn’t want to be, a warrior. For if I was going to be a warrior, it meant that comes a time I’d have to stop having ‘interesting debates’, and settle things by force. It was not something I aspired to ever do.

I find myself increasingly in situations where the culture of argumentation and debate that I dwell in is infiltrated by a warring culture of ‘shut up or else’.

I think the reason why this story came semi-consciously to my mind in the middle of the night is because, since the Gaza war, I have become more acutely aware than ever that when it comes to Israel/Palestine I find myself increasingly in situations where the culture of argumentation and debate that I dwell in is infiltrated by a warring culture of ‘shut up or else’. I cannot be certain, but I feel that this must have contributed to the difficulty I have writing about Gaza. It is not the fear of being bullied by and in that culture – I’ve got a much thicker skin than that. It is more the disgust at seeing it intruding and taking over my intellectual world. While nobody is threatening to put a gun to my head, being in Europe, particularly in Germany with its guilt-legitimised ‘sympathetic Zionism,’ and being subjected to all the taboos associated with speaking about Israel, one feels very strongly this state-sanctioned intrusion of a culture that normalises the usage of threat of force (fines, jail, withdrawal of research funds) to end complex intellectual arguments and put a limit on critical thinking: ‘say this or that and I will call the police on you’-type culture. I know this happens elsewhere. It didn’t happen in the Lebanon I grew up in, but I know it happens now. Call me a fool, but I still find it hard to believe that this is actually happening in the US and Western Europe. But it is. It still doesn’t happen in Australia, but it is creeping in: for example, debates about the difference between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, a difference that has a long history and that has involved very knowledgeable people who have spent years researching and trying to understand is now simply defined for us, a priori, by governments and by university administrations.

I feel that the Gaza war is firmly propelling us along a historical path where the ‘warrior’ will rule over the ‘intellectual’, a world determined to de-valorise the work of ‘thinking critically’ and where I, as an academic, will belong to less and less. Here is perhaps what is really making it hard for me to write. But I have. I’ve managed to do some carrion eating after all.