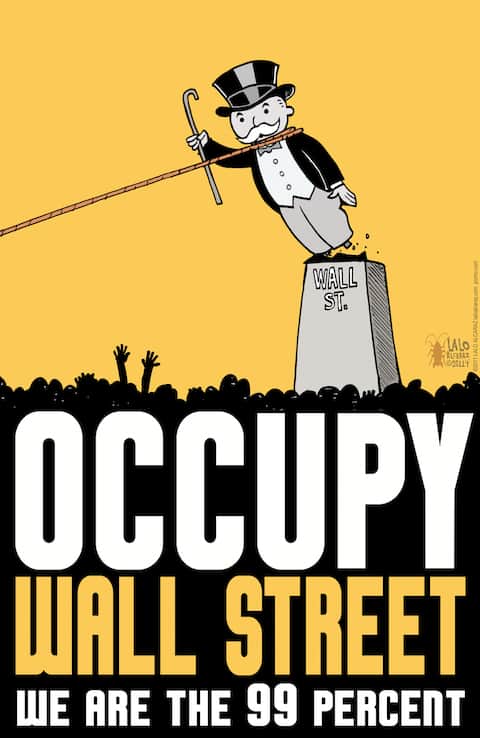

David Graeber (1961) is the author of several books on theories of value, social thory and anarchism, including the award-winning Debt: The First 5000 Years. For the wider public he is known for his involvement and visibility in the Occupy Movement, a global commotion born out of protests against the growing disparity of wealth, social inequality and corporate influence on democratic decision making processes. With his ample 25 000 Twitter followers he is also likely the world’s most visible anthropologist in the social media. Graeber was in Helsinki in mid-January 2014, for the Anthropological Knots Symposium. Juho Reinikainen had a quick chat with him for Allegra after a long day of anthro-talk.

Juho Reinikainen: How did you become an anthropologist?

David Graeber: Good question. I usually attribute it to my upbringing. My parents were sort of working class intellectuals, the house was full of books. I started reading anthropology books from an early age, my parents were interested in that sort of thing. At the age of twelve I became fascinated by codes and translating hieroglyphics, and I actually got discovered by some archaeologists and ended up going to some fancy high school as a result. They were planning on sending me off to become a Maya exporate. Needless to say, I got over that phase. But when I went to college I finally thought I want to become an anthropologist after all, as it was something I had been interested in, one way or the other, my entire life.

You are especially, at least to the wider public, known for your writings and opinions about anarchy and public movements. Can you tell me what is the current situation of the Occupy Movement?

At the moment Occupy has become a multiplicity of different projects, at least in the United States. It is not gone by any means but it has been broken into a whole range of things.

At the moment Occupy has become a multiplicity of different projects, at least in the United States. It is not gone by any means but it has been broken into a whole range of things.

For example, today there are people working on Occupy farms, there’s the debt movement, anti-eviction projects – almost anything you could possibly imagine. In a way I think these are all responses to the realisation that we are facing really heavy police repression in public spaces, which revokes the (US Constitution’s) first amendment in terms of freedom of assembly. When this repression began to occur and when the sorts of people we thought were our allies – the moderate left, progressive types – failed to come to our aid and help us make an issue out of this experience, we (the Occupy Movement) realized we had to get organised on a longer term perspective.

So I think that what people are really working on through the Occupy Movement is to build a culture of direct democracy and direct action. People are training to acquire new skills that facilitate organizing meetings and street action.

We’re gradually building a foundation so that in the face of the next financial crisis, the next natural disaster, we will be in the position to be the first ones out on the the streets doing something.

You talked about a major Occupy related movement in the Anthropological Knots symposium about students occupying a University building…?

Oh yeah, that is happening in London right now. Initially the student movement in London was organised actually before the Occupy movement; there were at least 14-15 student occupations occurring the same time as the earlier anti-cons[umerism] movement. In the first phase students protested against an educational reform which effectively semi-privatized the university system, a reform which momentarily vanished. Now the reform has really come up again, dramatically and quickly, out of nowhere.

I had sort of already given up on participating in the student movement, as I figured it was done, over. Yet suddenly there was a massive number of students fighting police in the streets. The government response has been much harsher and punitive than in the past – now the police just immediately started beating people up. This violence shows that the officials are in a state of panic because they really were not counting on this level of resistance. The nice thing is that the last time the educational reform was introduced it was a really defensive game for protestors as the officials introduce certain reforms before resistance was organized. This time, since we lost the battle during the first round, ironically, we’re now in a better strategic position because it is now us who are setting the agenda, we are the ones in the offensive. People are taking to the streets in order to restore the free university system, to change the basic idea of what education is supposed to be about . I think it is very exciting.

The Anthropological Knots Symposium was about anthropology’s role in engaging in the society. What is your opinion, should anthropology engage more in the lives of the people it studies?

I’ve always felt anthropology has something to offer. The way that the anthropological community resists when people want to contribute to change by protesting – the anthropological community almost has this reluctance for societal impact – I find a little difficult to understand. While I don’t think anthropologists will all go joining social movements […] few of you might actually lend your knowledge to people who want to use it to do some good in the world. Why not? [Scholarly life and activism] could actually be mutually enforcing.

So you think one can change the world with anthropology?

Did I say that?

No – do you?

I think anthropology has something to contribute to any project of social transformation.

How do you see the future of the discipline?

More internationalization of anthropology, which is going to lead into many different directions and different places. Anthropology could be constituted as a genuinely global planetary discipline, which could break free of the old colonial boundaries… and take advantage of that sort of diversity of perspectives to really enrich our self understanding.

One last question, which is a personal one: What are your hopes for the future?

Well, I’m sort of looking forward to a broad social revolution, which will eliminate the state of capitalism and, you know, a truly free society. But that’s a long-term project.

Juho Reinikainen is an undergraduate student in Social Anthropology at the University of Helsinki. He also videoed the Knots Symposium for Allegra.

Video of the interview is available here.

Other interviews of Graeber that are worth a read:

- On the topic of bullshit jobs in Salon

- About democracy in America for AlterNet

- On the Occupy Movement for Gawker

- “Finance is just another word for other people’s debts” in Radical History Review

- And, as a fun bonus, “What’s the Point if We Can’t Have Fun?” in The Baffler!

Brief bibliography of David Graeber:

Books

- — (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-24044-8. OCLC 46822270.

- — (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press (distributed by University of Chicago Press). ISBN 978-0-9728196-4-0. OCLC 55221090.

- — (2007). Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34910-1. OCLC 82367869.

- — (2007). Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Oakland, CA: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-66-6. OCLC 154704091.

- — (2009). Direct Action: An Ethnography. Edinburgh Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-79-6. OCLC 182529207.

- — (2011). Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Melville House. ISBN 978-1-933633-86-2. OCLC 426794447.

- — (2011). Revolutions in Reverse: Essays on Politics, Violence, Art, and Imagination. London New York: Minor Compositions. ISBN 978-1-57027-243-1. OCLC 759171790.

- — (2013). The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement. New York: Spiegel & Grau. ISBN 9780812993561. OCLC 810859541.

- As co-editor

- — (2007). Constituent Imagination: Militant Investigations / Collective Theorization. Oakland, CA: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-35-2. OCLC 141193537.

Articles

- — (December 27, 1998). “Rebel Without a God”. In These Times. Retrieved February 15, 2012. A meditation on the anti-authoritarian elements of Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- — (August 21, 2000). “Give it Away”. In These Times 24, (19). Retrieved February 15, 2012. An article about the French intellectual Marcel Mauss

- — (January–February 2002). “The New Anarchists”. New Left Review (13). Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (June 1, 2003). “The Twilight of Vanguardism”. Indymedia DC. Retrieved February 15, 2012. An essay originally delivered as a keynote address during the “History Matters: Social Movements Past, Present, and Future” conference at the New School for Social Research on May 3, 2003

- — (January 6, 2004). “Anarchism in the 21st Century”. Z Magazine. Retrieved February 15, 2011. Co-authored with Andrej Grubacic

- — (December 6, 2005). On the Phenomenology of Giant Puppets: Broken Windows, Imaginary Jars of Urine, and the Cosmological Role of the Police in American Culture. Retrieved February 15, 2012.Originally an address to Anthropology, Art and Activism Seminar Series at Brown University‘s Watson Institute, December 6, 2005

- — (March 2006). “Transformation of Slavery Turning Modes of Production Inside Out: Or, Why Capitalism is a Transformation of Slavery”. Critique of Anthropology 26 (1): 61–85.doi:10.1177/0308275X06061484. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (January 2007). “Army of Altruists”. Harper’s. Retrieved February 15, 2012. An attempt to solve the riddle of why so many working class Americans vote right-wing

- — (October 12, 2007). “The Shock of Victory”. Infoshop News. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (October 16, 2007). “Revolution in Reverse”. Infoshop News. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (April 1, 2008). “The Sadness of Post-Workerism, or, “Art and Immaterial Labour” Conference: a Sort of Review”. The Commoner. Retrieved February 15, 2012. An assessment of recent trendy autonomist theory (à la Negri, Lazzarato, etc.), with some comments on the relation of art, value, scams, and the fate of the Future.

- — (November 17, 2008). Hope in Common. Autonomedia.org. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (February 10, 2009). “Debt: The First Five Thousand Years”. Mute Magazine 2 (12). Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (November 2010). “Against Kamikaze Capitalism: Oil, Climate Change and the French refinery blockades”. Shift. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- — (December 7, 2010). “To Have Is to Owe”. Triple Canopy (10). Retrieved February 15, 2011. An illustrated essay on the history of debt, containing excerpts from Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011)

- — (September 25, 2011). “Occupy Wall Street Rediscovers the Radical Imagination”. guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- — (March 2012). “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit”. The Baffler. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- — (September 2011). “The Divine Kinghip of the Shilluk: On Violence, Utopia, and the Human Condition, or, Elements for an Archaeology of Sovereignty.”. HAU: The Journal of Ethnographic Theory. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- — (December 2012). “Dead Zones of the Imagination: On Violence, Bureaucracy, and Interpretive Labor. The 2006 Malinowski Memorial Lecture.”. HAU: The Journal of Ethnographic Theory. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- — (April 2013). “A Practical Utopian’s Guide to the Coming Collapse”. The Baffler. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- — (August 2013). “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs.”. Strike! Magazine. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- — (February 2014). “What’s the Point If We Can’t Have Fun.”. The Baffler. Retrieved February 15, 2014.