When Jon was a PhD student at Edinburgh University in the early 1990s, there was a running joke about the possibility of developing a project on ethnoscatology – a cross-cultural study of toilet habits. If the anthropologist’s cookbook could be written, it was reckoned, then why not the anthropologist’s toilet book? While several social anthropologists (and many biological ones) have dabbled in shit (notably Sjaak Van Der Geest and recently Steven Robins) a more comprehensive project never materialised, but recent years have seen a slow turn within the broader humanities towards things ‘of the bottom’.

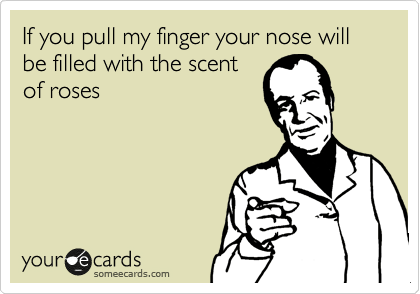

It was during Gavin’s mid-noughties doctoral fieldwork in Guatemala that a similar curiosity was piqued. While he can’t remember a time when he didn’t have a juvenile and scatological sense of humour it was seeing an American introduce an unexpecting Maya to the ‘pull my finger’ joke at a language school while enjoying a glass or two of quetzalteca that seeds of curiosity regarding the cross-cultural meaning of farts were planted. The combination of people who knew what to expect, people who didn’t, and a perfectly timed fart led to several of us laughing so hard it became hard to breathe (it was also at high altitude in their defence). The anticipation has escalated over a number of minutes as lots of ‘trust me – pull my finger’/’why should I pull your finger’ discussion went backwards and forwards. For the uninitiated, such finger-pulling involves proffering a digit to another person and asking them to pull it. As they do so, with a certain amount of skill and risk, the protagonist breaks wind at precisely the moment the finger is pulled. It is a classic joke structure insomuch as it concerns a derailing of conventional narrative expectation. No real bodily mechanism leads from finger-pulling to flatulence, yet a well-time fart suggests there is. In his defence it should be noted that Gavin was researching post-conflict violence at the time and sporadic counterpoints like this one were very welcome.

It was during Gavin’s mid-noughties doctoral fieldwork in Guatemala that a similar curiosity was piqued. While he can’t remember a time when he didn’t have a juvenile and scatological sense of humour it was seeing an American introduce an unexpecting Maya to the ‘pull my finger’ joke at a language school while enjoying a glass or two of quetzalteca that seeds of curiosity regarding the cross-cultural meaning of farts were planted. The combination of people who knew what to expect, people who didn’t, and a perfectly timed fart led to several of us laughing so hard it became hard to breathe (it was also at high altitude in their defence). The anticipation has escalated over a number of minutes as lots of ‘trust me – pull my finger’/’why should I pull your finger’ discussion went backwards and forwards. For the uninitiated, such finger-pulling involves proffering a digit to another person and asking them to pull it. As they do so, with a certain amount of skill and risk, the protagonist breaks wind at precisely the moment the finger is pulled. It is a classic joke structure insomuch as it concerns a derailing of conventional narrative expectation. No real bodily mechanism leads from finger-pulling to flatulence, yet a well-time fart suggests there is. In his defence it should be noted that Gavin was researching post-conflict violence at the time and sporadic counterpoints like this one were very welcome.

The hysterical audience for the floating of this particular air-biscuit included Maya, Ladinos, North Americans and Europeans. It was hard to tell who found it funnier, those who knew what to expect or those who didn’t. In that moment we were all brought together in the humour of wind.

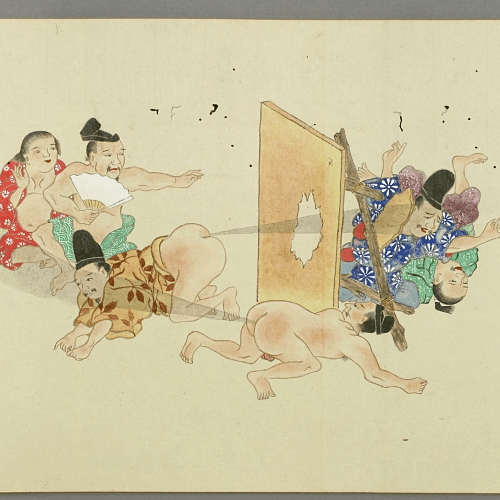

Such delight in flatus is not new. The first recorded joke, from Sumeria (now southern Iraq) dates back to 1900BC – “Something which has never occurred since time immemorial; a young woman did not fart in her husband’s lap.” It has perhaps lost some of its zing but still demonstrates the historical ubiquity of the comedic fart. Likewise ‘Japanese fart scrolls’ depict superheroic farts blowing cats into the air and felling trees; In Maori folklore Kahungunu uses comedically misattributed flatulence to break up a rivals marriage. Comedic flatulence spans across cultures and time. Colonel Gadaffi used to feed visiting dignitaries camel milk for his own amusement knowing that it caused explosive flatulence. Across history, sociology, cultural studies, a number of recent publications have cast their sensory organs – surely not eyes, but ears and noses – towards the fart. So why not anthropology? Should we be developing an ethnoflatology?

We were prompted to write this post by the recent popanth blog on farts across cultures. Here, Kirsten Bell argues that the seemingly universal ambivalence towards farts – their simultaneous fascination and revulsion – is to do with their transcendence of the body’s boundaries. Powerful yet ephemeral, they explode or leak from one body and then quite literally enter the bodies of those around. Perhaps this is the key to why our own farts always smell good – the re- ingestion of emission in an attempt to retain bodily integrity. As we know from both Sperber and Proust, smell is a particularly captivating and nostalgic sense, yet the smell of a digested madeleine seems unlikely to conjure the same remembrance of wind passed as the freshly baked.

In his account of A Secular Age, Charles Taylor contrasts secular and non-secular selves as non-porous and porous. The thing about secular modernity, he argues, is that it is characterised by the generalisation of a view of the self as bounded, integral, not prey to the intrusions of external, supernatural powers. A non-porous, or buffered, self means a non-porous body, which in turn means the regulation of all forms of porousness – including the fart. We have known for a long time that the regulation of the body is the regulation of power. The transgressive body is the powerful body. This goes for the porous and farty body as much as any other. Bakhtin’s vision of the grotesque body celebrates this porousness:

The grotesque body is not separated from the rest of the world. It is not a closed, complete unit; it is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits. The stress laid on those parts of the body that are open to the outside world, that is, the parts through which the world enters the body or emerges from it, or through which the body itself goes out to meet the world.1

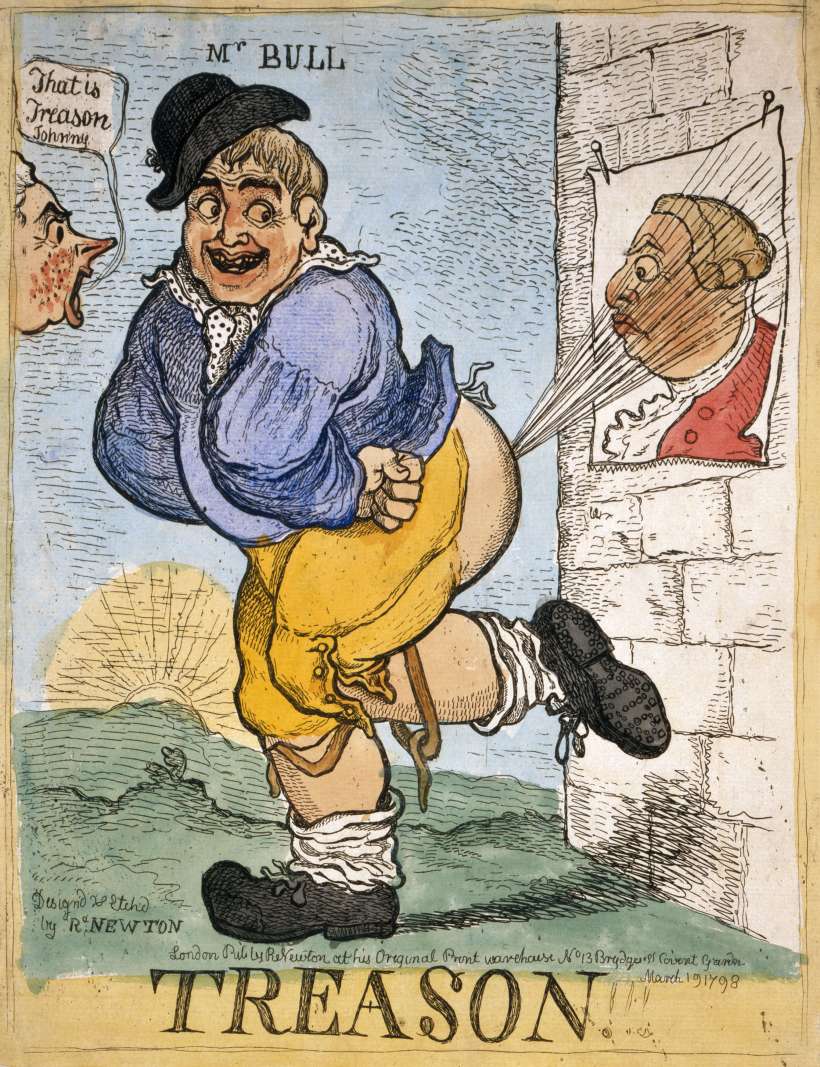

From this porousness derives its power of the carnivalesque – ‘a force that pre-exists priests and kings and to whose superior power they are actually deferring when they appear to be licensing. The permitted or sanctioned carnival fart acknowledges the revolutionary force of the carnival’2 carnivalesque fart, which can be lit to ignite the flames of revolt.

If repression is a litmus of resistance then we see the fart’s power in stories of those who fart in court or on police. But as with dirty protests, the bodily nature of the carnivalesue fart largely places them beyond the jurisdiction of the state. While Bell cites the Suya and Bororo as small-scale societies that do their best to prohibit wind, flatulence is largely beyond the realm of governmentality. Reports that circulated last year concerning legislation to prevent women farting in public in Aceh, Indonesia turned out to have originated in the online satirical paper The Wadiyan. Legislation that seemed to ban public farting in Malawi in 2011 led to international scrutiny and either a denial or climbdown scuppering the ban. While modernity is typified by the greater regulation of the body, it also forces us to recognise the unstoppable nature of our emissions.

If repression is a litmus of resistance then we see the fart’s power in stories of those who fart in court or on police. But as with dirty protests, the bodily nature of the carnivalesue fart largely places them beyond the jurisdiction of the state. While Bell cites the Suya and Bororo as small-scale societies that do their best to prohibit wind, flatulence is largely beyond the realm of governmentality. Reports that circulated last year concerning legislation to prevent women farting in public in Aceh, Indonesia turned out to have originated in the online satirical paper The Wadiyan. Legislation that seemed to ban public farting in Malawi in 2011 led to international scrutiny and either a denial or climbdown scuppering the ban. While modernity is typified by the greater regulation of the body, it also forces us to recognise the unstoppable nature of our emissions.

That being the case – it’s a good job they’re funny too.

1: Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 42

2: Michael Holmquist, Prologue, in Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), xviii