Today we combine two recent Allegra themes – both very dear to us – by revisiting a jewel from our archives: Reetta Toivanen on doing fieldwork with children, a post that was first published last June when we featured our first ever round of fieldnotes. We hope that this post serves as inspiration to the increasing number of us who are both parents and fieldworkers. As Carole McGranahan recently declared in her article that quickly became our most read post to date: you can be both a mother and an anthropologist. This is how!

Fieldwork with Children

The stereotypical anthropologist is a young bearded man going by himself to an isolated island in order to return one year later with a thick book of notes which he will analyse in his isolated office over the following years. The fact is that more and more of us are women and mothers, and more men admit the fact that they have also responsibilities towards their children. This is why we would like to launch a discussion on fieldwork with children: share yours!

In October 2013 I had no other option, once again, than to take my three-year old son with me on a research trip to South Africa and Namibia. My interest lay in making some initial contacts and conducting interviews with people (both academics and activists) who could help me to advance my research on San peoples and their efforts to get their rights recognized as indigenous peoples. This was by no means the first time that my son accompanied me. We were together, for example, in Northern Norway conducting research and interviews with Sea Sámi and Kven peoples (the Sámi are recognized as indigenous peoples and the Kven have been recognized since 2005 as a national minority of Norway).

The positive thing with having your child with you is that you get to know “normal” people very easily. Sometimes I am myself slightly shy in making contacts with people on the streets, camping areas, festivals or where ever; my son, on the other hand, has a very straight-forward attitude to finding new friends. He goes around asking everybody with his almost non-existent English: “Hey, what’s your name?” “What are you doing?” I can rely on his charm and openness and he forces me to start talking to strangers when translating his questions and then adding a few new questions of my own. Only working with the recorder and concentrating on the interviews can be at times challenging: he asks his own questions, wants things that he cannot have, touches things he shouldn’t and if nothing else succeeds in interrupting me, the last tool to get my full attention is the sentence: “Mami, wee-wee!” He has learned that this is incredibly effective! I wouldn’t say, however, that kids can and should be brought to all research settings. There are many interviews that cannot be carried out with smaller or older kids and not all people appreciate the presence of a little adventurer…

Nonetheless, the most difficult situations are less those where you make contact with people and actually interview them, and much more the whole travelling and nurturing of the child in situations in leave you worried and uncertain about whether it was a good idea to bring a minor with you to the “field” in the first place. This is a short entry in my field diary written after a long bus drive from Cape Town to Windhoek last autumn.

It is a few minutes past midnight in a waterless rotten toilet at the South African and Namibian border. I am squatting next to the toilet bowl trying to prevent my tree-year old from falling into the bowl. This has been going on for some twenty minutes but he keeps saying, “Mami, I am not finished yet…

I am worried. Worried because he is so sick and so tiny. Worried that we will not make it to the passport control and the bus to Windhoek will leave without us. His clothess are covered in what one can call shit and, as there is no place to wash, I just throw away his underwear and t-shirt. When he finally gives me the sign that we can move on, I grab him under my arm and run through the darkness towards the green light indicating the place for border control. I assume we do not look nice, nor do we smell nice. I guess my face looks too tired and worried, because the border police officer asks me to smile. Because that is the way Namibians do things, they smile, he commands. I try to explain that I do not actually feel very much like smiling; I feel rather more like crying. The police officer repeats: you smile because we have to smile too. I press an artificial smile on my face.

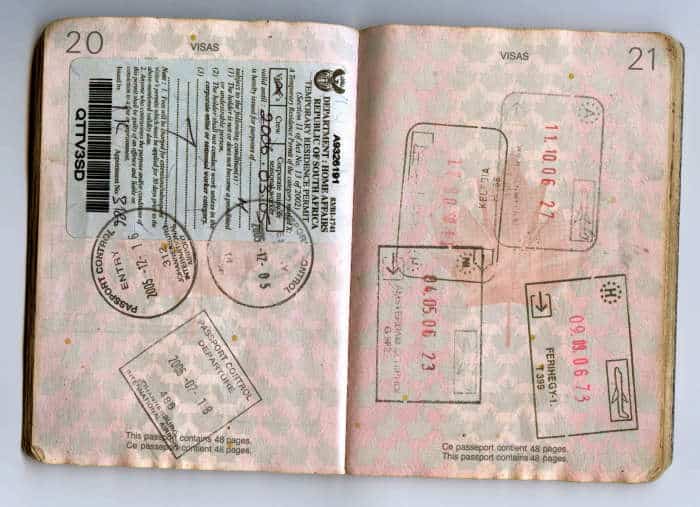

This is about to die in a few seconds as the police officer announces that my little boy was not stamped out from South Africa and that we must return there to get the proper stamp. At this point I cannot hide the fact that tears start running as I ask how on earth I could get back to South Africa in the middle of the dark night. The border police officer is not interested in my problem; he just says: “Next!” We go back to the bus, which at that moment is being searched for drugs (as it was just 20 minutes before at the South African border), ask for my suitcase and find some clothes for the kid. The bus driver is yelling at me, blaming me for the failure of the South African officer who forgot to put a stamp in my child’s passport. Tears are running again: is nobody worried about my son’s health? A Namibian lady steps out, takes our passports and goes to a border control officer standing next to his car. They say something in Damara and, suddenly, I find my son and myself in his car on our way back to South Africa. We get the stamp, return to the Namibian control and just when we are ready, the bus is declared clean and the trip to Windhoek can continue.”

Due to the two lengthy stints at the border controls with their thorough searches of the bus (for drugs and stolen items?) and a few new street constructions, the bus did not stop again but drove as fast as possible to catch up the delay. The remaining 11 hours without getting to any other toilet than the overflowing one in the bus did not make the trip as beautiful as I had imagined it would be, but we got see the amazing sun rising in Africa and made new wonderful friends with people travelling with us.

Nothing seems to bring people more closely together than shared experiences. My son also seems to remember the bright side of the trip, the funny girls who had been with their parents to see a doctor in Cape Town, not the night-time horror at the border control.

Combining children and fieldwork is maybe not the ideal combination if you hold the ideal, as I once did, that children and work are separate zones of life. Then, after receiving funding for a research project that was written without realizing that I might become a mother once again, I had to rethink my worldview. Kids are not always welcome additional guests; nor do most funding agencies pay any of the costs caused by the presence of children. But ever more parents work under circumstances in which they have no other option than to integrate a child-friendly approach to their work. We anthropologists are not an exception to this. Is it good or bad? Share your views!

Not nearly as dramatic and stressful as the case described here, but hearing about it recalled a much-treasured memory of how kids facilitate entry into local communities. When we moved into our apartment complex in Yokohama in 1980, my wife had classes to attend, and I had to find a job to supplement her grant. A top priority was finding day care for our four-year-old daughter. My wife noticed children lining up to be led to a local kindergarten, went over to introduce herself, and threw herself on the mercy of the mothers. Japanese being very susceptible to “poor-little-me” approaches, our daughter was enrolled in the kindergarten and one of the mothers volunteered to care for her after school until her mother got home from Tokyo, where her classes were. But the memory in question is from a few months later.

My wife was walking up the hill toward our apartment and passed two little boys. One, a visitor, instantly started pointing and shouting “Gaijin! Gaijin da!” (Foreigner!. It’s a foreigner!). The other little boy replied, “Gaijin ja nai yo! Kay-chan no obasan da yo!” (That’s not a foreigner! That’s Kay’s mom!”).

I related very much to your post. Last year I completed my doctoral fieldwork in Mexico taking along my then 5yr old and was also 7 months pregnant- giving birth halfway through and continueing in the field. On top of that I left my then 3yr old back in the UK with my husband so our family was separated for most of the year. I blogged about my experience throughout (www.letterfromchiapas.blogspot.co.uk). You’ve just reminded me that I never got round to my concluding post! Having my daughters with me made fir a truelly unique experience and being separated from my son and hubby made it a deeply emotional one that I still have very mixed feelings about.