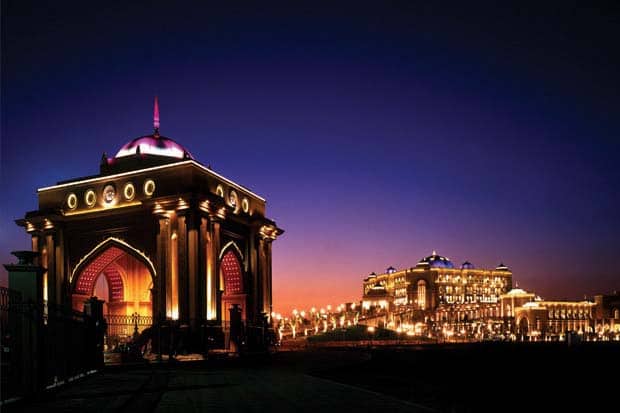

Huge skyscrapers in the middle of the desert. The city looks like a mega shopping mall. On my way from the airport (through which I passed only 4 months ago on my way to Australia) to the Five stars Sheraton hotel where we are accommodated, we pass by Shaykh Zayed Grand Mosque, one of the world’s largest mosques that can host 41000 worshipers and has one of the heaviest chandeliers as well as the largest hand made carpet in the entire world (at least, so the website visitabudhabi claims). In this city state, size does seem to matter.

Unfortunately, I won’t have time to visit anything in Abu Dhabi except luxury hotels and restaurants. Highways, 6 by 6. Who lives here? My Indian cab driver has welcomed me with these words: “Welcome to Abu Dhabi, the best place in the world!”. He has left his 2 kids and his wife in India to work and make money in this glass town. He says money is better in Abu Dhabi than in India. He returns to India once a year, for a couple of months, and he skypes with his kids the rest of the time. Here he is the majority as 83% of the population comes from outside of the Emirates. Also, he will remain the majority as no one can become Emirati: nationality is exclusively reserved to those born here. “It’s easy to get a work permit, but don’t ask for any rights. Either you like it or you leave it!”

I have been shipped over to this strange place to give a 2-day course on gender and development to 20 Afghan civil servants from the Ministry of Finance. This course is part of an Executive Master’s Program on Development Policies and Practices provided by the Graduate Institute in Geneva and funded by the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) . It is quite ironic that after having written on the absurdity of trainings on gender given by Western ‘experts’ to Afghans over the past 10 years as a part of US-NATO military occupation, I find myself in the position of participating in this business too. I guess I have accepted this invitation because I thought I could provide a different sort of training and because ‘money is good’, as my cab driver insists. I also thought it would be an opportunity for me to catch up with Afghanistan, where I have not returned since the time of my fieldwork in 2007. I was curious to capture the Afghans’ feelings on the evolution of their country’s situation. In a couple of months, NATO troops will withdraw and most of the donors that currently support the (almost non existent) state apparatus will do the same. How do Afghans feel about that? How do my students as state representatives envision their future and that of their country in general? With the quasi ‘state of emergency’ that has increasingly become the norm in Afghanistan with every passing day, how do these civil servants feel about receiving training on ‘gender and development’ in a five stars hotel in Abu Dhabi? From the dust of Kabul to the bling of Abu Dhabi…in only a few hours’ flight.

I have been told that the location of the training has been chosen by UNITAR, which had preferred that the training take place outside of Afghanistan for “security reasons”. I wonder how this reassures civil servants about the future of their state when even a small training raises security concerns.

So here I am now, in a 5 stars hotel with view over the sea and a magnificent swimming pool, wondering how I will introduce these questions about gender and development that have more to do with international governance than with real demands ‘on the ground’. My colleagues from the Graduate Institute tell me that the minister had personally insisted for ‘gender’ to be included in the program. How can this be, and why, when only a handful of women work in this ministry and only one woman has been selected to attend this program?

Once I arrive, I learn that the Afghans are being accommodated by a different hotel than the persons doing the trainings. The logic behind this is, according to my colleagues from the Graduate Institute, that the privacy of the trainers should be maintained. Yet the practical outcome remains that, like in Kabul, a separative wall exists between the Afghans and the expats not allowing for any genuine encounters to occur.

With all these contradictions in mind, I direct myself towards the private beach of the hotel called the “blue lagoon”. The name seems somewhat exaggerated as in reality the lagoon consists of a few square meters of white sand over a small sea pool with a view on skyscrapers under construction. Thus, while the rich are sunbathing and drinking fancy cocktails, the migrant workers from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh doing their 8 hours shift can watch them from the scaffoldings overlooking the beach and the pool. But there is no need to feel bad about it, because – the hotel informs me – it sponsors a charity specialised in the protection of the environment, and guests can easily contribute to the charity’s efforts should they feel guilty for having eaten too much at the outrageous offerings of the breakfast buffet.

Now the speakers disposed on the beach are playing Lambada. The hotel staff carries frozen smile stuck on their faces and asks each guest they encounter in a mechanical manner: “How are you today, M’am?”

Gender Expertise

There is only one female participant in the room. Her name is Khatera. She told me that she managed to continue her studies during the Taliban thanks to relatives who lived in Nooristan and accommodated her so that she could go to school. The province was not under Taliban control and schools still functioned. When she returned to Kabul after the regime fell, she passed the entrance exam of Kabul University and was granted a place to study economics. She is now working in the budget department of the Ministry. She says that there are very few female employees because finance is perceived as a technical, and therefore, a masculine discipline. Khatera is not married: “I want to find the right person”, she explains.

The other participants are mostly department directors (internal audit, customs, budget, revenue, policy, human resources, IT etc). They are in their thirties or forties. Some have graduated from Indian or Pakistani universities. One of them studied in Australia. Very few of them have a beard. They all wear Western style costumes with ties.

The course on gender and development has been designed by the ‘gender studies department’ of the Geneva Graduate Institute. However, I have been able to suggest readings and was left completely free of the lectures’ content. I have prepared an introduction to ‘gender and development’, in order to place historically the apparition of gender in the global development agenda.

I have designed a course that emphasises on the contradictions and ambiguities of projects for gender justice in Afghanistan, imposed by external actors and presented as non political. I have given them a text by Chandra Mohanty as an introduction. I was careful to highlight the underlying assumptions of such projects and I thought it was necessary to start from there so that none of us would have to play the ‘good consultant’ or the ‘good civil servant’. To my surprise, they seemed unimpressed by such precautions. They seemed to be willing to get standard guidelines for integrating gender concerns into their work. So my attempt at deconstructing and criticizing the gender and development nexus was not what they really expected.

Phantom State

In the Hilton hotel of Abu Dhabi, Afghan civil servants were longing for the state and to a great extent, the workshop was a way to make the state exist, a way to concretise the state. They acknowledged that institutions were weak, that state institutions enjoyed little legitimacy, that corruption was widespread and diminished the already very limited trust people had in the state…but still, they believed in the necessity to have a state to run the country. “I am very optimistic”, the director of the audit department told me at lunch. “We have made progress already and when the international community will withdraw, we will be ready to take over”. But to take over what? A few computers and some buildings?

How ironic that the training, as a form of governance and performance of the state, was held outside of Afghanistan. This contradiction powerfully illustrates the fact that the Afghan state is an external business. That Afghans do not have ownership of the state.

There is an inherent contradiction between Afghans’ desire for a state and the ironical comments they make when referring to it. The comments participants made during the training illustrated this tension. This made me think of Navaro-Yashin’s writings on Northern Cyprus where the non-recognition of the state by the international community has created this affective tension among Turkish Cypriots who wish to get a job in a public administration in spite of their absence of trust in the state.

Another civil servant from the department of audit explained to me that the length of administrative procedures in Afghan institutions was the legacy of the Communist regime. For instance, to have one’s school diplomas validated by the state can take several months, sometimes years, people being forced to run from one administration to another, to collect all the stamps that are necessary for their diploma to become officially recognised. He also explained that these procedures are means to ‘make the state exist’…in other words, make the state real in a context where the sovereignty of the state is constantly challenged: by international organisations, NGOs and citizens who do not trust the state because of the corruption they experience on an everyday basis. In the meantime, these lengthy procedures are, in his view, an effective means to avoid the circulation of ‘fake diplomas’ which have become a widespread business.

References :

Yael Navaro-Yashin, ‘Make-believe Papers, Legal Forms and the Counterfeit Affective Interactions Between Documents and People in Britain and Cyprus’, Anthropological Theory, 7 (2007), 79-88.

Yael Navaro-Yashin, ‘Affect in the Civil Service: a Study of a Modern State-system’, Postcolonial Studies, 9 (2006), 281–294.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty.’Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourse‘. Boundary 2, Vol. 12, no. 3 (Spring – Autumn, 1984), pp. 333-358