Every day, women, men, and children sit on the wonky wooden benches in front of the social welfare office, patiently waiting to present their matters to one of the social workers. ‘Dysfunction’ or ‘failure’, one could say, forms the daily business of the office: Individuals who ‘failed’ to build their own life and families which did not hold together make up most of the cases. However, not everyone leaves with the desired letter granting certain rights or forms of support. Only if one can prove to be in need and deserving, the social workers will open a file and start (re)negotiating responsibilities of care between various actors such as family and community members, religious leaders or state agents.

Drawing on 12 months of ethnographic research in the Department of Health in a district in Northern Tanzania I explore the daily interactions between the social welfare officers and their clients and the processes that lead to categories such as ‘failed’, ‘in need’ and ‘deserving’. Several cases illustrate how the officers maneuver in concrete situations and reveal the application of different categories and the underlying meaning of what it means to be a ‘proper’ citizen.

‘Failure’ at the heart of the state

According to Didier Fassin, the state is produced at institutions such as social services and “reveals itself” through the institutions’ professionals (2015:15-16). By looking at the concrete actions of those professionals it is, therefore, possible to grasp the politics of the state and to gain “insight into the ‘heart’ of the state” (ibid.:14-15). The “agents of the state” (ibid.) in this contribution are four social workers who operate in two offices in a district council in Northern Tanzania. Their working areas include violence against children and domestic quarrels, services to poor elderly (e.g. the issuing of exemptions according to pro-poor policies implemented in 1994 to ensure equitable access to health care, see Maluka 2013) and people with disabilities, and support of children in conflict with the law. ‘To fail’ – or kushindwa in Swahili – in this context means to not reach established expectations of how “to succeed, to live a good life, to realize one’s values and to discharge one’s responsibilities” and is thus a relational category (Zoanni 2018:62). Looking at the negotiations of state welfare through the lens of failure offers an understanding of the underlying societal dynamics and how it shapes society (see Carroll et al. 2017:4).

Negotiating care: Failure, need and deservingness

An elderly man, neatly dressed in jacket and suit trousers, walks into the office and greets us politely. Still standing he explains to Eric, a Social Work student who is volunteering during his semester break, that he needs an exemption for free medical treatment at the governmental hospital. Eric asks back whether he has a letter from his chairperson. In order to receive free treatment, Eric lectures the old man, he needs an introduction letter from the chairperson of his village. The man seems a bit at loss, staring at Eric. He did not expect such obstacles. Irene, one of the social workers, walks in with another client asking what is going on. When Eric explains, she intervenes. After a quick look at the man and a few questions about his place of residency, she prompts Eric to write the requested letter. She turns to the old man and repeats in a friendly tone that the correct procedure usually requires a letter from the village chairperson, so as to prevent wealthy elderly from receiving free treatment.

The man seems a bit at loss, staring at Eric. He did not expect such obstacles.

That someone has ‘failed’ to live a ‘successful’ life needs to be proven by the local government: Operating on the grass-roots level, village chairpersons are expected to know the residents of their unit as well as their circumstances. The introduction letters thus present a first step in negotiating the need and deservingness of a client in question and serve as a primary ground for the social workers’ decision to grant or deny their request. In practice, however, many clients come without a letter or with letters issued incorrectly, and the social workers must decide on other grounds. Since need and deservingness “are negotiated both on an individual and on a societal level” (Thelen 2015:505), it is in these interactions between the social workers and their clients where the state comes into practice and reveals established forms of classifications and categories.

In the case of the old man, Eric, a rather inexperienced student, adhered to the required procedure and rejected the client’s request. Irene took a more indulgent approach and granted the letter. Having worked in the office for several years, she had developed a trained eye and was able to categorize him easily as a poor elder above 60. Despite mentioning the possibility of fraud, his need and deservingness seemed obvious to her. Irene’s immediate decision relates to the agency’s efforts to grant free access to medical care for poor elderly within the district and mirrors the governing party’s emphasis on elderly care. Although the old man could not prove his political belonging as a righteous citizen within the district – a prerequisite to receive state support – he could convince Irene that he failed (ameshindwa) to pay for his medical bill and deserved free medical treatment. Discretion thus plays a key role in the negotiations of each case, since cases hardly ever fit into the rigid categories of bureaucracy.

Discretion thus plays a key role in the negotiations of each case, since cases hardly ever fit into the rigid categories of bureaucracy.

Past noon, a woman with a small girl following her shyly steps into the office. The mother’s restrained and simple appearance, dressed in a kanga (a rectangular colorful cloth) wrapped around her hips and a shirt tucked inside, points to the rather poor circumstances of peasant life. I remember them from a couple of days ago: The girl was bitten by a dog and needed medical treatment. James, another social worker, wrote a letter for the hospital to grant free medical treatment as well as an injection against rabies. The girl is still limping and gives a weak, almost apathetic impression. James is worried about her state and writes another letter to continue with the injections. He calls the village chairman who is responsible for the girl. Although I cannot follow the whole conversation, I understand that James, visibly upset, threatens the chairman to be held responsible if the child dies. He starts writing a letter to the chairman and asks the mother whether they had already caught the owner of the dog. She answers in the negative, and James writes another letter to the police to order the prosecution of the dog owner. “So that she [the girl] gets her rights” (“apate haki zake”), he adds. Before they leave with several letters for the hospital, the police and the chairman, James calls at the hospital to ensure the girl’s immediate treatment. The child is “most vulnerable”, he states, and makes yet another call.

Categories such as ‘failed’, poor, or most vulnerable are thereby negotiated individually and present the necessary features to gain access to state support.

The case of the young girl constitutes another interesting example since she was already above five and thus above the age to receive free medical treatment for children. James nevertheless decided to grant her an exemption by categorizing her as “most vulnerable”. The protection of the children, based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (OHCHR), presents another main emphasis of the social welfare office and – besides the deathly threat of rabies – forms the background of James’s decision. Categories such as ‘failed’, poor, or most vulnerable are thereby negotiated individually and present the necessary features to gain access to state support. The leeway social workers are given in handling such situations does not necessarily reveal a weak state but shows “a specific way for the state to exert power over its population” (Dubois 2014:42). Accordingly, having ‘failed’ does not automatically grant state welfare as the following case demonstrates.

Failed to belong

On a rather calm morning a man in dirty and worn out clothes enters the office. I notice a strong smell of urine when he sits down across from me. He presents his matter to the intern behind the desk, muttering that he has problems urinating ever since he had an accident and needs a new tube for his catheter. I notice the stains on his pants. The intern seems rather perplexed by his request when James walks in. He looks down on the man sitting slumped on his chair and prompts him to repeat his request. After posing a few questions, James turns towards the intern and lectures her about the groups who would receive exemptions: elderly and persons with disabilities, children and cancer patients. The man, who is staring quietly at the tiles on the ground, doesn’t belong to any of these categories. James turns back to him and asks about his place of residence. Family? Wife, children, other relatives? The man mumbles something about a deceased wife and one child, no relatives. Asking further about his place of residence he cannot come up with a place except the bus stand. James puts his pen down and leans back in his chair. Without relatives, it is a challenge. He at least needs an introduction from his village chairperson. Otherwise his hands are tied. The man nods slightly and James sends him away. When he is gone, James explains in a staunch tone that he could not give him money; the police would catch him and accuse him of stealing. Besides, he would buy alcohol instead of the tube anyway. If he had known him, James adds, he could have written a letter immediately.

Although the need of the man was obvious, the question was whether he deserved state support. His unwillingness – or inability – to state where he lived as well as his appearance led James to the conclusion that he was a homeless alcoholic who wanted to exploit the social system. That he mentioned the bus stand only fed into this assumption. Not being able to name any relatives nor having a relation to any of the agents reveals his actual failure: “The excluded are excluded by virtue of their failure to be part of something” (Edwards/Strathern 2000:153). The man failed to prove any kind of belonging and thus could not access state support. In their daily interactions with the clients, the state agents mobilize “values of good and bad, right and wrong, true and false, and feelings like compassion or indignation, empathy or suspicion, admiration or hostility” (Fassin 2015:256). In that sense, James’ decision reflects not only his personal aversion but “values and sentiments prevalent within the public realm and political discourse” (ibid.). Accordingly, the actual failure of the man was not his precarious living circumstances but his shortcomings in being a ‘proper’ citizen: The impression of a drunkard without a place of residency or a family made him an outcast of society undeserving of state support. James’ suspicions were reinforced when he saw the man a few days later at the bus stand, drunk.

Looking at the three cases through the lens of failure enabled to reveal the negotiations of care in the context of state welfare and the application of different categories such as ‘failed’ (kushindwa), ‘in need’ and ‘deserving’. The everyday interactions between the social workers and their clients thereby “play a key role in the delivery of public services, in the implementation of state policy, and, consequently, in the definition of what the state actually is” (Dubois 2014:39). The applied categories range between “big structural categories of encompassing relevance” and “the myriad of categories with small and medium societal scope” (Nieswand 2017:1719) and guide the course of each case. ‘Having failed’ and being ‘in need’, however, does not necessarily mean to deserve state support. Only if one can present him- or herself as a ‘proper’ citizen the social welfare officers, “vested with the power of the state” (Dubois 2014:38), pick up their pen and open a file.

References

Carroll, T., D. Jeevendrampillai, and A. Parkhurst. 2017. Introduction: Towards a General Theory of Failure. In The Material Culture of Failure: When Things do Wrong. Timothy Carroll, David Jeevendrampillai, Aaron Parkhurst, and Julie Shackelford, eds. Pp. 1–20. London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Dubois, V. 2014. The State, Legal Rigor, and the Poor: The Daily Practice of Welfare Control. Social Analysis 58(3):38-55.

Edwards, J., and M. Strathern. 2000. Including our own. In Cultures of relatedness: New approaches to the study of kinship. Janet Carsten, ed. Pp. 149–66. Cambridge [England], New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fassin, D. 2015. Introduction. Governing Precarity. In At the Heart of the State: The Moral World of Institutions. Online-ausg. Didier Fassin, ed. Pp. 13–20. EBL-Schweitzer. London: Pluto Press.

Maluka, S. O. 2013. Why are pro-poor exemption policies in Tanzania better implemented in some districts than in others? International Journal for Equity in Health 12(80):1-9.

Nieswand, B. 2017. Towards a theorisation of diversity. Configurations of person-related differences in the context of youth welfare practices. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(10):1714–30.

Thelen, T. 2015. Care as Social Organization: Creating, Maintaining and Dissolving Significant Relations. Anthropological Theory 15(4):497–515.

Zoanni, T. 2018. The Possibilities of Failure: Personhood and Cognitive Disability in Urban Uganda. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 36(1):61-79.

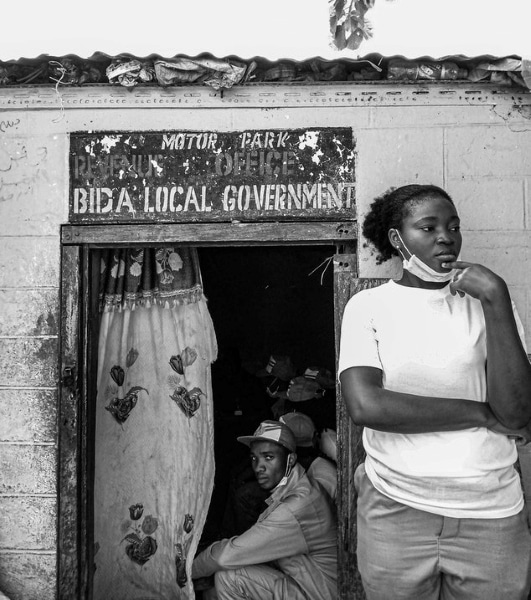

Featured image by erinbetzk (Courtesy of Pixabay)