“We will continuously say how rooted we are in this county like a plane tree embracing the soil with its roots. They might prune our branches, but they won’t be able to reach the roots of our old tree.”

(Embros, 15 September 1955, in Agos 6 September 2013)

“You know that the future means nothing other than the shitting of the past; whatever we do, we will not be able to change this fact, unless a miracle happens.” (Heba, Hasan Ali Toptas.)

A rusted projector reflects a film on the big screen between worn-out velvet curtains some American movie, in the dusty, damp-smelling, high-ceilinged auditorium —an old ice-skating rink, on the old Grand Rue de Pera, in a complex of buildings called Serkildoryan (Cercle d’Orient in French), commissioned by an Armenian banker close to the Ottoman palace, and designed by a Levantine architect in the late nineteenth century. Under the celestial ceiling decorated with withered and faded engravings bathed in dirt and rust, on one of the broken velvet chairs, a woman with a hardly discernible face sings uncannily. I move to the sound, towards her, to see her face; it has no surface.

Her voice is reminiscent of Rosa Eskinazi, an Istanbulite Jewish-Greek singer, who passed away in forced exile in Athens in the mid-20th century.

Chagrined and in discomfort, Roza the ghoul laments an epoch long gone. Moved, I move out of the movie theatre through a corridor of broken stained glass and mirrors. I look at one of the broken mirrors to catch a glimpse of my shaken self only to hesitate at the sight of my reflection: my face does not lend itself to reflection. Haunted, I rush out of the theatre to be met by the ear-trenching noise of jackhammers and construction machinery, disemboweling the old building under a barricade of hardblock covering the carvings and ornaments of its hundred and twenty years old facade —a ghoulish remnant dating back from the forced property transfer of the Wealth Tax in 1942[1] and the pogrom of 6-7 September in 1955.[2]

Here, Taussigian defacement (1999) has appendages. The old facade, no longer discernible, discharges the ghoulish surplus of the melancholic energy of the displacement and plunder resulting from the Wealth Tax and the 1955 pogrom. These events served the reproduction of Turkified citizens who “know what not to know,” thereby instituting a public secret concealing the violent uprooting of the city’s non-Muslim and non-Turkish citizens, together with the plunder and transfer of their properties to the newly fabricated Muslim-Turkish bourgeoisie. The surgical particle-board bandage over the facade of Cercle D’Orient reveals a new form and reality of desecration, by exhibiting a surface affect of cleanliness and capitalist progress, while once more despoiling an already plundered building before turning it into a shopping mall.[3]

If evacuating those buildings and evicting and uprooting their inhabitants constituted the separatist logic of the Republic, these sites are marked as ghoulish left-overs of a non-Turkish and non-Muslim urban presence: disemboweling Jewish, Armenian, and Greek building remnants behind flat, expressionless board fences reveals the current practice of plunder and displacement, which seemingly aims to uproot anyone and anything that does not conform to the current government’s pseudo-Dubai-style aesthetics.[4]

It is no coincidence then, when, on 7 December 2012, police forcibly evacuated another shop in the Cercle d’Orient, the 68-year-old Inci Patisserie. The Turkish owner of the patisserie -the apprentice of Lukas Zigoriadis who had endured the 1955 pogrom – provided cauldrons of soup for protestors camping on one of the side streets of the building, thereby resisting the new wave of forced displacement, plunder, and property transfer. Then, on March 31st, around 300 protestors, most of them members of an anti-gentrification coalition, which had been working against the demolition of the historical Emek theater located in Cercle D’Orient, occupied the building against riot cops who were hunting for them. On April 7th, 2013, just a month and a half before the Gezi Uprising, police attacked with water cannons and tear gas to disperse a group of thousands, including Greek-French director Costa Gavras and many actors who protested the demolition of the movie theatre, with drunkards and homeless of downtown Istanbul joining them.

On April 7th, teargas and a barricade made of large flower pots marked the new boundaries of the entertainment centre of the city.

Imagine a curiously diverse group of people made of clochards, vagabonds, glue sniffers, drunkards, passersby, students, teachers, writers, journalists, artists, actors, directors, cinema lovers, architects, musicians, and activists, choking and chanting against the tear gas, all in nervous pulse, trepidation, and uproar. It was as if parts of the life experience of those people choking in tear gas and chanting slogans against riot cops had been the accumulative acquisition of an uncanny familiarity with the melancholic facade of Cercle D’Orient, which was forcibly squeezed behind and erased by a hoarding. Had those people not spent some time acquiring that haptic experience, then they would perhaps not feel the building and see nothing extraordinary about jackhammer cracks deforming its historical carvings.

How Cercle D’Orient impresses me will depend on what I deliver to it as affective fragments —my countless strolls and visits to the building, flashback memories, erratic images of defacement that the building calls to mind, the piquant shock of the teargas, affective thoughts I have harvested from books and discussions with friends; in short, my visceral experiences.

Cercle D’Orient’s façade here, like the face of Deleuze and Guattari (2008), is this intertwined operation of defacement and vacuuming: The hoarding covering the old facade is nothing but a flattened out (post-Ottoman white, bio-male, heterosexual, raced, classed, and tyrannical) screen of consumerism, which sterilizes suggestions that there might be something behind it discharging expression. Behind the board fence, there exists an affective reservoir of knowledge —a tormented ghoul signaling an ineffable and injurious secret of defacement to be transmitted from one generation to the other (Abraham 1994 [1975]: 176); that something has been going terribly wrong here; that that there is “something-to-be-done” and this involves a “futurity” (Gordon 1997).

Cercle D’Orient’s façade here, like the face of Deleuze and Guattari (2008), is this intertwined operation of defacement and vacuuming: The hoarding covering the old facade is nothing but a flattened out (post-Ottoman white, bio-male, heterosexual, raced, classed, and tyrannical) screen of consumerism, which sterilizes suggestions that there might be something behind it discharging expression. Behind the board fence, there exists an affective reservoir of knowledge —a tormented ghoul signaling an ineffable and injurious secret of defacement to be transmitted from one generation to the other (Abraham 1994 [1975]: 176); that something has been going terribly wrong here; that that there is “something-to-be-done” and this involves a “futurity” (Gordon 1997).

Some of the slogans and graffiti of the Gezi Uprising —such as “Oppression started in 1453,” “Who is living in Dimitri’s house?” and “Turk, Rum, Armenian, Jew, long live the brotherhood of the people” —must be understood in this context of historical defacement in downtown Istanbul. If the series of events and protests that culminated in the Gezi Uprising have been suggestive of a chaotic and deranged landscape, then I understand Gezi as the type of miracle described by Toptas in Heba —a miracle that has incited a violent crack in the unfolding of history, and created a moment of resonance by challenging the Turkish subject’s nearly psychotic insistence on not feeling for his surroundings and not accounting for its specters.

In other words, if the death of affect (Ballard 1974) signifies the lack of care for and understanding of one’s immediate surroundings, then the uprising has brought forth a ghoulish sense of solidarity: Here some urban dwellers resist AKP style of defacement, and attempt to reconnect by seeing through wounds, cracks, scars, fissures, vomits, bile, blisters and the like…

Like its predecessors, the current government portrays non-Muslim non-Turks and their pillaged properties as an “outside,” associating them with debris, and turning them into scapegoats (Benlisoy 2013).

Yet, with Gezi, the hoarding has become suggestive of the one dimensional face of the current government or even its facelessness, as it displays its impulsive urge to erase alterity, memory, and ethics to replace them with blood and profit. Gezi has momentarily exposed the epistemic murk produced by a war-monger regime that attempts to conceal its hereditary thirst for plunder, its lust and greed for capital, and its urge to kill life and memory behind hard block covers. Unlike Levinisian ethics (1985) -which idealizes face-to-face encounters as sites of sterling and uncontaminated relatedness by locking the self and the undeniable yet sentimentalized Other into a relationship of debt while excluding the sensory experience of buildings- with Gezi, the facade of the historical building resists becoming a static and finite product that pseudo-Dubai capitalism enacts.

Here, faces and facades are accumulative, cut, putrescent, squeezed, vomiting, and therefore suggestive and dynamically turned in anxiety and anticipation towards something-to-be-done; waiting not only for the teargas and the plastic bullets, for further plunder and displacement, but also for miracles like Gezi.

To Pera kids

Inspired by strolls with Ceren Oykut, Defne Sandalci, Jesse Gagliardi, Nilgun, Uber Lazy, Yael Navaro-Yashin and Yasemin Nur Erkalir.

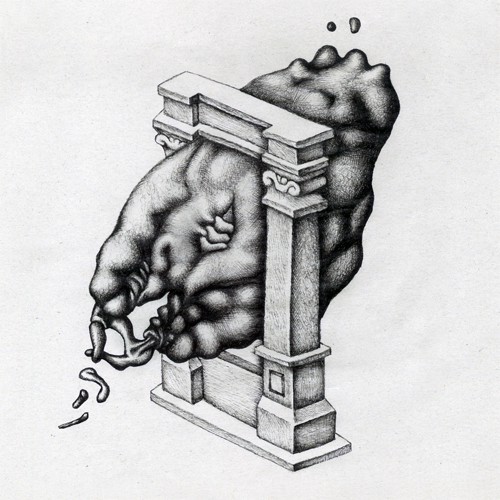

Art Work by Bora Başkan

References

Abraham, N. 1994 [1975]. Notes on the Phantom: a Complement to Freud’s Metapsychology. In The Shell and the Kernel: Renewals of Psychoanalysis (eds) N. Abraham & M. Torok, (trans. N. T. Rand), 171–177. Chicago: The University Press of Chicago.

Adanali, Yasar Adnan. 2011. De-spatialized Space as Neoliberal Utopia: Gentrified İstiklal Street and Commercialized Urban Spaces.

J.G. Ballard. 1974. Introduction to the French Edition of Crash reprinted in Vale and A Juno eds.

Foti Benlisoy. June 2013. Gavurun Pesine takilan Gezi direnisi.

Fahri Coker. 2005. 6-7 Eylul Olaylari: Fotograflar -Belgeler. Fahri Coker Arsivi. Istanbul.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. 2008. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans., Robert Hurley, et al. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP.

Dilek Guven. 2005. 6-7 Eylul Olaylan. Istanbul.

Avery Gordon. 1997.. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. University of Minnesota Press.

Emmanuel Levinas. 1985. Ethics and Infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo, trans. R.A. Cohen. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Michael Taussig. 1999. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford University Press.

Hasan Ali Toptas. 2013. Heba. Iletisim Yayinevi. Istanbul.

Footnotes

[1] The extraordinary law called Wealth (Capital) Tax (Varlık Vergisiin Turkish), which was executed by the National Assembly in the Single Party era in 1942 eradicated, in its implementation, the pioneering role that Armenians, Greek Orthodox, and Jews had had in the economy. “An economic genocide” for non-Muslim non-Turkish minorities, as well as a project of Turkification that created economic and political opportunities of re-emplacement for the muslim Turkish bourgeoisie (Aktar 2006: 15). The tax was sometimes so excessive that it was even impossible for the non- Muslim non-Turks to pay it even if they sold all of their possessions. The punishments were levy, confiscation, the mandatory labor camps, and forced exile. Following the Wealth Tax, the Cercle d’Orient complex was bought by the municipality.

[2] The 6-7 September Pogrom (Septemvriana in Greek) was a government-instigated series of plundering and looting acts against the Greek minority of Istanbul in September 1955. Greek, Armenian and Jewish residents of Istanbul were targeted. People organized in coordinated gangs committed acts of violence in neighborhoods and districts where non-Muslim non-Turkish populations were mostly concentrated. Residences and shops were mined and pillaged; their contents wrecked, thrown into the streets, trailed behind vehicles and churches; community schools and cemeteries were vandalized. The material damage was considerable, with damage to 5317 properties, almost all Greek-owned, and among these were 4214 homes, 1004 businesses, 73 churches, 2 monasteries, 1 synagogue, and 26 schools (Guven 2005). The death toll was dozens of people.

[3]The Cercle d’Orient complex, transferred to the municipality following the Wealth Tax and bought by the Pension Fund following the Istanbul Pogrom, is now owned by the Social Security Administration (Sosyal Guvenlik Kurumu, SSK), and thus constitutes public property. The building was leased to a private developer who plans to demolish it from within in order to turn it into an entertainment and shopping complex. Demolition work started in 2013. In January 2015 the 9th Istanbul Administrative Court rejected the request to stop demolition and reconstruction, and the Regional Administrative Court reversed the decision. The decision stated that the previous legal proceedings were not in compliance with the law. The reconstruction continues despite the decision.

[4] A political economy of moral and social engineering, dressed in the paradoxical language of Islamic grandeur and vulnerability, compartmentalizes the city into classed yet detached hubs of profit havens via urban corridors and transportation infrastructures that will facilitate the flow of capital, goods, and humans (Adanali 2011).