Today we are delighted to share this exchange between Antu Sorainen and Davina Cooper on the latter’s project & book on Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces. The project started in 2001 on “prefigurative community governance”, focusing on democratic schools, Speakers’ Corner, and alternative currency systems, and has since expanded to include also the university, a topic of recurring interest also for Allegra.

An exchange with Davina Cooper

By Antu Sorainen

Davina Cooper is Professor of Law and Political Theory at Kent Law School where she established the AHRC Research Centre for Law, Gender & Sexuality in 2004. She has been one of the key intellectuals in the field, writing at the interstices of socio-legal studies, political theory and the transformational potential of state and non-state sites. Cooper has published books that have been widely influential not only in socio-legal studies but also in social sciences, gender studies, legal anthropology and queer legal studies. As her work has centered on transformative politics, it has enabled critical scholars to look at the potentiality for social diversity and equality in terms of gender, sexuality and law.

In Challenging Diversity: Rethinking Equality and the Value of Difference (2004), Cooper explored the tensions between affirming diversity and undoing relations of inequality, engaging with debates in Britain, EU and Northern America, through linking theoretical discussion to specific conflicts over social and cultural issues, such as religious symbolism and lesbian and gay marriage. In Governing Out of Order: Space, Law and the Politics of Belonging (1998), she problematised ideas of governing in liberal states, asking how it could be both responsible and radical at the same time, arguing that governing principles should be ideologically explicit, prepared to contest and transgress divisions of authority to pursue a multi-cultural, egalitarian vision of political responsibility. In Power in Struggle: Feminism, Sexuality and the State (1995), Cooper provided a radical re-thinking of the concepts of power, sexuality and the state, and their interactions, while in Sexing the City: Lesbian and Gay Politics within the Activist State (1994) she discussed sexual politics and alternative social change strategies.

In Challenging Diversity: Rethinking Equality and the Value of Difference (2004), Cooper explored the tensions between affirming diversity and undoing relations of inequality, engaging with debates in Britain, EU and Northern America, through linking theoretical discussion to specific conflicts over social and cultural issues, such as religious symbolism and lesbian and gay marriage. In Governing Out of Order: Space, Law and the Politics of Belonging (1998), she problematised ideas of governing in liberal states, asking how it could be both responsible and radical at the same time, arguing that governing principles should be ideologically explicit, prepared to contest and transgress divisions of authority to pursue a multi-cultural, egalitarian vision of political responsibility. In Power in Struggle: Feminism, Sexuality and the State (1995), Cooper provided a radical re-thinking of the concepts of power, sexuality and the state, and their interactions, while in Sexing the City: Lesbian and Gay Politics within the Activist State (1994) she discussed sexual politics and alternative social change strategies.

Davina Cooper’s most recent work focuses on the conceptual lives of everyday utopias. In her newest book Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces (Duke, 2014) she explores how concrete everyday utopias work and how they influence our wider imaginings of social justice and equality. Based on six small-scale case studies, Cooper looks towards “forging a social justice politics of change” in the current context of rapid legal and political change and other issues in society – issues that might go beyond the “ah yes” moment. Her rich research literature extends across such fields as feminist theory, socio-legal studies, political theory, utopian studies, queer theory, moral philosophy as well as legal anthropology.

Davina Cooper’s most recent work focuses on the conceptual lives of everyday utopias. In her newest book Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces (Duke, 2014) she explores how concrete everyday utopias work and how they influence our wider imaginings of social justice and equality. Based on six small-scale case studies, Cooper looks towards “forging a social justice politics of change” in the current context of rapid legal and political change and other issues in society – issues that might go beyond the “ah yes” moment. Her rich research literature extends across such fields as feminist theory, socio-legal studies, political theory, utopian studies, queer theory, moral philosophy as well as legal anthropology.

The idea of Everyday Utopias is to engage with six existing small-scale everyday utopian sites from a progressive perspective. Cooper’s intention is not to assess critically the politics of these sites but to explore how they actualise concepts differently (how they put them into practice) and how they provide a basis and impetus for a wider conceptual reimagining that refashions what concepts such as property, equality, the state, and markets might mean and come to mean. The sites studied vary from two world-famous British institutions –Summerhill School and Speakers’ Corner – to the less well-known Toronto Women and Trans Bathhouse, and three everyday utopian practices: LETS, equality governance and public nudism. These different sites and spheres are involved in the daily practice of education, public expression of one’s views, engaging in semi-public sex and moving in a sexual space, alternative trading, governing and appearing in public space.

The six case studies in Everyday Utopias vary in their relation to the hegemonic, normative and mainstream, and also in their relation to public and private. These differences are interestingly linked in the book by the paradoxical idea of the everyday and the utopian, and by the impossibility of the utopian providing the perfect place. Cooper first introduces her readers to the idea of a utopian conceptual attitude, which concerns the potential of everyday utopias to contribute to a transformative politics through the concepts they actualize and invoke. The target of everyday utopian places is thus not to focus on campaigning or advocacy but on building and forging new ways to experience social, political and sexual life.

In the six corresponding chapters, Cooper elaborates this core thesis of her book by clarifying how each of the studied sites, in its own way, articulates the building of alternatives to dominant practices. In the concluding chapter, she summarises how the potential of everyday utopian places may inhere within the present but “only because a future is imagined and brought to bear on imagining and guiding what is manifested in the now”. Cooper argues that the capacity of progressive practices to drive new forms of imaginings lies at the core of the utopian conceptual attitude, since the utopian does not emerge from dreams and fantasies alone. Everyday Utopias also emphasises, however, that there is no single “conceptual line”, no one way of moving between the imagining and actualisation of concepts, as both practices and social imagining make a multitude of conceptual lines possible.

It is refreshing to read Cooper’s non-assessive analysis of everyday utopians which leaves open a wide intellectual landscape for meditation wherein the reader may try out her own attitudes, experiences and ideas of the utopian. There is indeed enough critique elsewhere to be found on the utopian, both as an idea and as concrete places. Everyday Utopias offers a way out of the pessimistic approach to the utopian, in particular by underlining pleasure as one of the most important aspects of concrete utopian places – therefore, it also offers the reader a pleasurable space to think about what pleasure in utopia could entail.

This is important because, even though hegemonic society and literature widely support cynical views on the utopian and the alternative, it feels a necessary struggle to re-conceive ourselves in terms of a social justice which we could imagine – even if it is not yet (or anymore, as in the crumbling Nordic Welfare societies under the reality of neoliberal and right-wing governments) – as possible to live and experience in material actuality.

I had the rewarding opportunity to discuss the core ideas of Everyday Utopias in an email exchange with the author, Davina Cooper. I am pleased to share our exchange with Allegrareaders.

The utopian as “a critical proximity upon the Mainstream”

Antu: – In Everyday Utopias, you apply the term progressive in a positive, affirmative sense. Would you like to clarify for Allegra readers what you mean by progressive: from what scholarly lexicon, scholarship and intellectual tradition are you looking at things when you use this term? It seems to me that in your writing and thought an encounter takes shape between Foucault’s and Marx’s treatments of power, disciplinary power, cases and sovereign decisions. Would you like to reflect on this or do you disagree?

Davina: – I use progressive as shorthand for a left-wing agenda, some might describe as radical democratic, or as feminist and green socialist. Progressive, for me, is a very open, broad term. It suggests an orientation or compass, a way of facing towards a particular set of political desires rather than writing in a final imagined vision of what the world should be like. But in terms of my writing, over the past twenty-five years, it has had many academic influences, including, as you say, Foucauldian, and Marxist. They inform the ways I think about power, institutions and change – from the debates between structuralism and poststructuralism to newer debates about culture and materiality. But my engagement with academic texts always feels politically driven. I grew up in a household where politics was talked about extensively. Mainly, it was a politics oriented to critique, but it also took shape as a politics of re-imagining, fixed on the challenge of how to build other ways of living. This inheritance has continued, I think, to shape how I approach academic texts.

Antu: – Yes, I have understood that along with your academic career you have been politically active in local politics in London. I tend to look at your academic career and leadership as thoroughly political in the sense that political theorist Kari Palonen has underlined in his work on political thought and conceptual change; that is, that everything we do, every event, is inherently political and should be treated accordingly. For example, I admired the policy of the Centre LGS (Research Centre for Law, Gender and Sexuality) for inviting not only academics but also authors and artists such as Sarah Waters and Alison Bechdel to conferences and visits. In that way, the academic everyday life and community extended into the art sphere and practices, and it created a possibility for it to re-imagine itself in new ways. But back to your new book: what prompted you to think about everyday utopias in the first place – it must have been a long intellectual process?

Davina: – Everyday utopias started as a project in 2001 on “prefigurative community governance”, focusing on democratic schools, Speakers’ Corner, and alternative currency systems. Gradually, other sites got added. I wanted to explore sites that performed seemingly commonplace activities – trading, schooling, appearing in public, having sex etc. – in ways that were innovative, non-conformist, and radical (at least in part).

What engaged me was the convergence between these two contrasting principles: on the one hand, the everydayness of being imperfect, near at hand, with rules and established ways of doing things; on the other, the utopian quality of being experimental, innovative, and intent on prefiguring a better world.

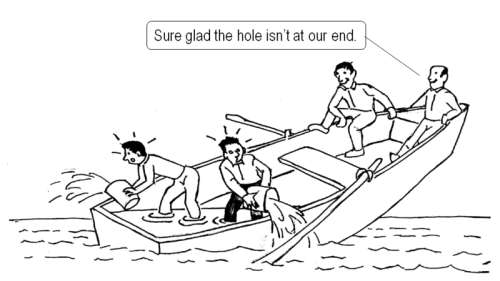

An important quality of everyday utopias, making them different to other kinds of intentional communities, is that they don’t involve a departure from mainstream life. People weave participation through regular, often conventional (in other respects) lives. So, they can involve many different kinds of people. Everyday utopias also affect the mainstream through the ways they are entwined with it, in relationships of critical proximity, rather than the critical distance more commonly associated with utopia.

So, I think of the local currency-scheme members engaged in innovative new forms of trading who grumbled about people showing up late or the distance they had to travel to trade; or the volunteer providing sexual services at the Toronto women and trans bathhouse who described how she had to maintain a decent pace so a queue didn’t build up outside her door.

Politically, I think, the ease of access, the involvement of diverse people, and the imbrication of everyday utopias with mainstream social practices are crucial aspects.

Counter-sites for concepts

Antu: – What made you think of conceptual lines – what does “conceptual” mean in your writing? You argue in the book that conceptual scholarship has a tendency to focus on mainstream and hegemonic relations and practices. Could you elaborate on this view?

Davina: – My writing has always focused intensively on concepts – at the start, this wasn’t intentional; it just seemed to be the point around which the questions I asked came to circle: how should we think about power, citizenship, the state, property and so on?

In Everyday Utopias I approach concepts from the perspective of the visitor – the one who, entering a new innovative place, tries to make sense of the unexpected ways of living witnessed there, while gaining critical insight on the home-world temporarily left behind. That’s how it works in much utopian fiction anyway. What I wanted to do was to take this boundary straddling figure as the place from which to explore the work of concepts; what they “do” in everyday utopias, and how such spaces, from democratic schools to local currency networks, can inspire and stimulate (without necessarily advocating or instantiating) other kinds of conceptual understanding.

So, this is a process with two parts. The first relinquishes a conventional approach that considers concepts through, and in relation to, mainstream practices. Even when this isn’t done explicitly, concepts such as property, the state, care, and equality tend to be imagined in ways that make it possible to see the trace within them of conventional life.

For instance, when someone thinks about ethical care, often their first thought is parenting, nursing or something similar. If they then seek to build normative conceptual accounts, these contexts will structure the possibilities for how care is approached. We can see this in feminist care ethics. If mainstream life is the basis for progressive or radical conceptualising, it is going to shape and, in particular ways, limit how conceptualising is done.

Everyday utopias provide counter-sites for conceptualising. If we start, for example, with the rather unlikely subject of nudism when thinking about equality, if we start with a women and trans bathhouse in thinking about care, or a democratic school when thinking about property, different ways of approaching these concepts get opened up. It’s impossible to know in advance what these will be.

But there’s a second dimension to the conceptual framework explored in this book. This dimension leaves behind the conventional view of concepts as slices of thought and instead approaches concepts as the movement between imagining and actualisation. In other words, concepts are in flux – they identify the continuous oscillation between what’s imagined, and what materialises; and to the extent this oscillation acquires a particular distinct shape, thanks to the social processes and actors through which it is generated and instantiated, we can think of it as a “conceptual line”.

Approaching concepts in this way raises many questions: how do imagining and actualisation draw on and incorporate each other; what political work is performed by their divergence; can they ever converge; and perhaps most crucially, why treat materiality or actualisation as an integral dimension of concepts rather than as the object or site of conceptualising? I try and address these questions in the book.

One overall aim, though, was to avoid concepts’ reification. I wanted to foreground the co-existence of multiple ways of conceptualising, say, care or equality without assuming one conception was necessarily best.

Conceptions emerge in different contexts to do different things. And other, related, concepts may do similar work. I don’t want to argue that care is a more ethical concept than justice, for example. This doesn’t abnegate the place of political value. In general, for instance, I prefer a conception of equality as undoing relations of domination and hierarchy, and moving towards equality of power, compared to more liberal formulations, such as equality of opportunity or desert. But I also recognise that a more transformative conception of equality identifies a politics that can be expressed, in different contexts, through different conceptual lines. I don’t want to freeze equality.

Concepts, for me, are social phenomena that do social things. They can be developed and created in new ways, but their material dimension (even as this keeps getting imaginatively re-framed as understandings of concepts change) structures and limits how concepts develop. We can try and develop concepts at a distance from current understandings and usage; for instance, we might deliberately re-imagine the state as a pleasure formation, but if this reconceptualization goes nowhere – if it doesn’t impact on social practice, if it remains unrecognised – it is then a kind of phantom concept.

Concepts are mobile social phenomena that we engage with in various ways, including by seeking to hold up or transform the “lines” they take.

We can see this in the new conceptual lines developing around the definition of marriage in the USA. Evolving kinship arrangements, particularly through “out” lesbian and gay families, in conjunction with more inclusive imaginaries of marriage (at least in gay terms) have unsettled prior conceptions of marriage. But there’s no single conceptual line when it comes to marriage. The movement between imagining and actualisation will be differently experienced and differently forged by liberal marriage proponents, conservative opponents and various radical ones – in terms of how practice and imaginaries are framed and connected up. At the same time, mediating practices, such as marriage law, will strengthen certain conceptual lines over others.

Thinking from, and away from, certainties

Antu: – As you are focused on what concepts can do, would you like to clarify the meaning of your term “transformative politics” – it comes to fore in lots of your argumentation in Everyday Utopias.

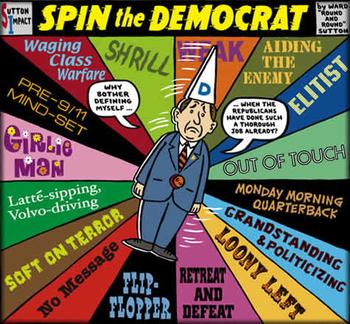

Davina: – Talking about left-wing politics has become a fraught business; how do we find inclusive umbrella (or short-hand) terms through which to do so? Over the years, I have moved between the terminology of left, socialist, radical, critical, and progressive – each has its own problems, limitations, ambiguities and historical baggage.

Davina: – Talking about left-wing politics has become a fraught business; how do we find inclusive umbrella (or short-hand) terms through which to do so? Over the years, I have moved between the terminology of left, socialist, radical, critical, and progressive – each has its own problems, limitations, ambiguities and historical baggage.

Transformative tries to capture the notion of a politics oriented to significant change to create a more equal, democratic, environmentally sustainable, culturally heterogeneous, internationalist world, where economic relations are subordinated to, and rendered meaningful by, the pursuit of social well-being; where militarisation and profit motives are foreclosed (and ideally eliminated) so they don’t govern people’s lives; where the arts, culture and play are foregrounded, supported and given time; and where lives are lived in more communal and public ways – if not exclusively.

When I read Ruth Levitas’s book Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (2013) recently, I thought: this gets close to the kind of transformative changes I would like to experience.

Antu: – Why do you see it as important for critical, dissident and/or dissent academics to try to work away from what we already think we know?

Davina: – That’s a good and difficult question. There is, I think, a tension between creating intellectual work, which seems instrumentally to advance progressive and radical causes, and embarking on work whose outcomes, and even sometimes whose directions, appear unclear. My own view is that there is a place for both. It is important to have work that makes strong and convincing arguments in favour of particular positions (treating these as unquestionable givens), including work which critically evaluates specific developments, policies and changes from clear and settled political stances. I like this work and learn a lot from it, but it has not ended up being what I do academically. Why, I’m not too sure; but I seem to use my writing to help me think – so I think from, but also away from, my own certainties.

Let me give you an example. In researching Summerhill School, property was a theme that kept emerging in interviews. I’d thought originally that the school would be a good case-study for thinking about democracy, so the recurrence of property in what people said surprised me. My attitude to property at this point reflected the general critique and wariness many on the left hold. At the same time, it became clear that for property to be a meaningful concept to address in relation to Summerhill, traditional notions of property as state-recognised exclusion, dominion or as a bundle of rights would be of limited value in understanding what people were saying and in understanding how the school worked. Legal pluralism helped by opening up other possible sources and sites of property recognition. At Summerhill, the school meeting develops, passes, amends, withdraws and adjudicates on dozens of laws each year, including in relation to what people can do with their “things”.

But multiplying the sites where laws can be made and adjudicated upon didn’t feel enough. It seemed to me property played an important part in sustaining the school’s variegated life, but this wasn’t property as exclusion or even just property rights of access, use and alienation. It had far more to do with relations of belonging than of belongings.

And so, my conception of property changed as I explored the social work that relations of belonging performed. This didn’t mean I ended up with a form of property that I thought was unproblematic – relations of belonging have their own drawbacks (particularly of non-belonging), but it did, at least, provide a less commodified way of approaching property.

For me, following this conceptual line – through diverse imaginings of property and belonging, and through the social practices and organisation of Summerhill School – took me to ways of thinking that I hadn’t anticipated and to ways of working with property that I hoped might (in broad terms) have some resonance with other contexts where left-wing scholars are trying to support minoritised or subordinated relations of belonging rather than just critiquing dominant property relations. Sarah Keenan has done some very interesting work here.

But your question of whether left-wing academics should choose to write and think towards uncertainty, to privilege uncertainty in a sense, is a difficult one. Maybe for “dissident” academics it’s clearer since the anti-hegemonic takes priority over the counter-hegemonic, but for left-wing academics who explicitly want to advance certain political commitments, there is a tension between doing academic work that supports settled truths and work that seems to undo them. Some processes and practices seem so obviously wrong that to be uncertain about them feels dangerous; at best, it’s a rather dubious luxury to feel we can question the wrongs – or deconstruct the terms so that they become unusable – of poverty, environmental degradation, or racism. At the same time, as a general political and intellectual stance, an attitude of certainty can also be dangerous and unappealing. Perhaps we need a mix of both.

Changing one’s pace contains costs and risks

Antu: – How, do you think, do concrete utopias suffer from the hectic pace of the now? Could this be linked to the increasing reach of neoliberal management in our societies – and if so, in which ways?

Davina: – The question of pace and “time-scarcity” is an interesting one for the everyday utopias I discuss. Where it came through, in my research, most keenly was in relation to local currency networks (LETS). Some people wanted these to replicate mainstream “time-efficient” economic norms; other people saw their value in the counterpoint they offered to capitalist time pressures. This friction was, I think, a major factor in LETS decline in the UK. Part of the problem was that LETS (and other local currency networks) took shape within wider societal frameworks with their own, often incompatible, temporal norms and unequal time allocations.

Davina: – The question of pace and “time-scarcity” is an interesting one for the everyday utopias I discuss. Where it came through, in my research, most keenly was in relation to local currency networks (LETS). Some people wanted these to replicate mainstream “time-efficient” economic norms; other people saw their value in the counterpoint they offered to capitalist time pressures. This friction was, I think, a major factor in LETS decline in the UK. Part of the problem was that LETS (and other local currency networks) took shape within wider societal frameworks with their own, often incompatible, temporal norms and unequal time allocations.

So, while many LETS members appeared to applaud a more relaxed approach to time, they lacked the space within their own lives to live it out. This is a challenge, I think, for many initiatives within neoliberal societies such as “slow food”, “slow cities”, or “slow universities”. Changing pace is important, or maybe to live according to a range of paces, but pace is often something people cannot significantly control. Making decisions to radically change one’s pace tend to generate costs and risks people are unprepared to take.

For instance, Summerhill School has a very different pace to more conventional schools. It doesn’t prioritise formal academic achievements, classes are non-obligatory, and kids can spend their time playing if they prefer. Many of the young boys, I observed, spent hours riding their bikes around the school forecourt or honing their skateboarding skills.

I like the idea of children having far more control over how they spend their time; and Summerhill children know a huge amount about democracy and communal living because they practice it (and, I mean, really practice it). But their school-oriented lives are pretty different to those of affluent kids in middle-class neighbourhoods in the global north who go between highly structured school environments to highly structured out of school activities, taking music, dance and other classes, performing in teacher-directed plays, doing competitive sports, visiting friends and having masses of homework.

If childhood has become ever more accelerated and compacted – if it is now, at least in middle-class households, an ever more urgent investment in accruing educational and cultural capital, it becomes harder and seemingly riskier for parents and kids to choose a school environment with a very different temporal ethos. Unsurprisingly, many parents who choose Summerhill do so because their kids are failing to flourish in more conventional high pressured environments.

How, then, might we move from a context where slower, less pressured spaces are outlets for those not thriving within the mainstream to one where places with, say, Summerhill’s tempo or rhythms become more like the norm? I don’t know, but it seems important.

The political value of strangers meeting

Antu: – Where does the enduring nature of some concrete utopian places – for example Summerhill and Speakers’ Corner in the UK, come from? These places have survived several generations of “users”, changing social conditionings, and heavy disillusionments. Some of them have also become world famous institutions, cultural heritage of a sort, tourist attractions. What does this mean for their meaning as concrete sites to “forward new kinds of social relations”, as you write in Everyday Utopias?

Davina: – Some sites last because they meet ongoing needs, as in Summerhill’s provision of a different kind of school experience; some because they meet continuing pleasures, such as for public nudism; some survive even though the driving motivations for their use significantly changes. Speakers’ Corner, for instance, initially endured because it was an important place for public speech and debate, particularly for those who for reasons of their politics, class or national origins lacked access to other, more elite or institutionalised outlets.

Today, Speakers’ Corner survives, I think, for other reasons. It’s a place of sociality for its regulars, one that is free, accessible, relaxed and stimulating. Regulars facilitate the Corner as a place of public discourse that can be also lively, irreverent and funny; they provide some of the oratory, but also act as hecklers and initiators of one-on-one conversation. And because the Corner endures as a place of public debate, to which one-timers attend, regulars can go and enjoy the company of other regulars as well as stimulation from newcomers.

Today, Speakers’ Corner survives, I think, for other reasons. It’s a place of sociality for its regulars, one that is free, accessible, relaxed and stimulating. Regulars facilitate the Corner as a place of public discourse that can be also lively, irreverent and funny; they provide some of the oratory, but also act as hecklers and initiators of one-on-one conversation. And because the Corner endures as a place of public debate, to which one-timers attend, regulars can go and enjoy the company of other regulars as well as stimulation from newcomers.

The presence of strangers is an essential aspect of the Corner’s survival and character; as it is also of the Toronto bathhouse I discuss in my book. Strangers offer diversity and stimulation; they allow speech and sex to be interesting because they provide its “unknown”, sometimes challenging, dimension.

At the Toronto bathhouse, I was told, having sex with people you didn’t know was highly valued. At Speakers’ Corner, regulars I talked with said that not knowing where a conversation would go was what kept it interesting. Both places provide instances of edgework – disorienting risky play with strangers. But people at the Corner also described the political value that came from strangers meeting, where people living in different parts of the world or across major divides, such as Israel/ Palestine, would have an opportunity to talk with each other in a relatively safe, common domain. Interestingly, these conversations were often brokered by regulars.

But in exploring why everyday utopias endure, the presence of constraints, prohibitions, and counter-pressures are important considerations, even though they don’t always work in predictable ways. Summerhill fought off a government attempt about fourteen years ago to close it down through its removal from the private school’s register. Thanks to media attention and community mobilisation, interest and admissions to the school as a result, it seems, went up. LETS, in contrast, struggled to be sustainable and to grow. While time constraints proved a major issue, government threats to deduct welfare payments for LETS work, insurance concerns, lack of trust within communities, and the difficulty schemes had in involving people with very different skills in order to create diverse markets were also factors. Lots of people I spoke with grumbled that all you could get on LETS were massages and candle therapy. This wasn’t quite true. But there was a shortage of building skills and fresh food, which many people who joined LETS were looking for.

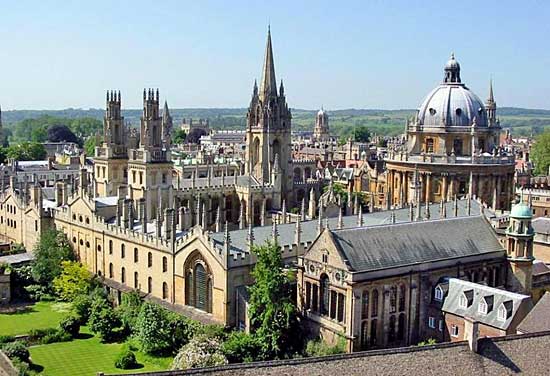

Universities still have utopian potential

Antu: – But let us look to another crucial site that is increasingly troubled place for academics – also close to many Allegra readers and discussed in previous posts – the University under neoliberal management and administration. Henry A. Giroux recently argued that education is now largely about training, creating an elite class of managers and eviscerating those forms of knowledge that conjure up what might be considered dangerous forms of moral witnessing and collective political action: “The corporate university is the ultimate expression of a disimagination machine”; adjusting themselves to the reality of neoliberalism, universities worldwide are turning increasingly toward corporate management models and marketization. Could you offer your experience/views on this, from the UK perspective?

Davina: – I don’t disagree, in general, with critical analyses of the corporatisation and marketization of universities, although I think many students still get (or maybe “participate” is a better word) in a vibrant progressive or critical education – at least in terms of the content of what is taught and discussed. Universities also continue to produce radical, challenging scholarship and politically engaged academics. But what particularly interests me, from my experience of British universities, is the potential they have as everyday utopias of work. I know this is a very contentious claim. Academics in the UK grumble about university working life and what it is becoming – more bureaucratic, more pressured, more goal oriented. There is also the huge problem of casualization, and of hierarchy both between universities as well as within them, particularly between academic and non-academic staff.

But despite all of this, my experience of working in a British academic department is that, compared to many other kinds of jobs, it’s a place where collaboration and collective accountability have some place (at least as an aspiration), where there still remains some autonomy, and where there’s room for creative work. These qualities may be declining but they still are there to some degree, at least for some workers. In my view, it’s the exclusive character of this experience that is a big part of the problem.

Academics, I think, at least in Britain, have far too readily sought to protect this way of organising working life for ourselves, such as through discourses of “academic freedom”. What we have been less good at doing is arguing for the expansion of democratic, autonomous, collaborative, trust-based, creative ways of working, where managerial positions rotate, into other occupational areas and other kinds of work.

Antu: – Thank you very much for this interview, Davina! To conclude, would you like to tell Allegra readers what you are working on now?

Davina: – Thanks Antu, and for your challenging questions, which have got me thinking harder about the processes and genealogies of academic work. Right now, what I’m engaged in is working with the conceptual methods explored in Everyday Utopias to think more explicitly about the state. I’m interested in how we might conceptualise the state when we are oriented not so much to its critique as to its transformation. So, my current work presupposes we need different ways of conceptualising the state tuned to different tasks.

Like many others, I worry about the discursive closing down of political, economic and social alternatives, so that in a country such as Britain, the present forms of work, politics and consumption seem all that is available. I am interested in how we imagine alternatives and the contribution academic work might make to this.

Anarchist activists and writers have been very active in building and talking about other, non-state based ways of organising political and social life. I’ve found their arguments really helpful. But building a political project against the state seems, to me, to overly reify it. I am interested in other ways of thinking about the state, oriented to a future in which it is less dominating and, in a sense, more banal.

Anthropological work has been particularly helpful for me here in trying to think about the state in more plural, socially entangled ways. Maybe the language of the state is unhelpful given the institutional baggage it carries. But as with property, I’m interested in how we can stretch our conceptions of the state into forms that may be productive for imagining and supporting progressive, transformative developments.

Fundamentally, I’m interested in questions of public responsibility. Governing is a process, and approaches to the state which treat it as some kind of edifice are not always helpful. But if we ignore the forms of organisation and embodiment through which governing takes shape – if we just focus on the “how” of governing rather than the “what” – it seems to me it then becomes harder to think about holding, but also developing, public responsibility for the quality of life we collectively experience.

Davina Cooper is an active blogger, look at her blogs here.

Check out also Margaret Davies ‘s wise review on Everyday Utopias here: http://equality.jotwell.com/2014/03/