I would like to use this opportunity to reflect on the long journey of ethics that I, as the PI of a project taking place in eleven non-European countries, dealt with over several years. I raise the multiple challenges that emerged in the bureaucratic process in relation to politics of knowledge-making as native scholars. By native scholars, I do not aim to discuss nativeness – which is addressed in this collection by Mezna Qato. Instead, by using the term, I simply refer to the scholars whose expertise aligns with the geography they grew up in and the complexities this brings to the operations of ethics bureaucracies.

This essay focuses on four primary issues aroused in the ethics clearance processes imposed institutionally by both funding bodies and host institutions. The issues I touch on are: 1) the persistence of unrealistic stereotypical perspectives on the geographies (i.e. South Asia and the Middle East) and themes (i.e. Islam) expected to be addressed by the scholars, 2) questioning the scholars’ expertise, 3) the ethical aspects of additional paperwork and its burden on native scholars, and 4) how to change the language of the processes, so that the unique position of native scholars and their deep, thorough, and intimate knowledge on the geographies they develop expertise on would be reflected as a strength. Several steps in the ethics review processes I describe below are familiar to those who held externally funded projects. Yet they will also see some of the structural issues I address here and the added administrative load often placed on the shoulders of native scholars.

The project title is “Imaginative Landscapes of Islamist Politics Across the Balkan-to-Bengal Complex”, although we often refer to it by its acronym, TAKHAYYUL. The project is built on the premise that theories of imagination are too Eurocentric to capture the internal rationale of its operations in political formations, especially populist ones. To overcome the Eurocentrism embedded in political theories, the project team developed a heuristic concept, takhayyul, an Arabic concept that refers to terrestrial imagination that informs both doxastic and futuristic thinking towards developing an Islamic shared vision (Sehlikoglu 2024). The team does so by developing an ethnographically-informed theoretical analysis, researching in the following countries: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Turkey, Iran, Palestine, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

For the proposal reviewer experts who were able to read the project proposal closely, the project’s aim to move beyond radical Islamism as a scholarly focus and be able to locate the populist forms of Islamisms vis-à-vis other populisms was crucial. Yet, the bureaucracies of the ethics processes often surface the very scientific problems the scholars of social sciences are spending their lives to address.

The Ethics of Too Much Ethics

The ethics processes for such grants have two layers: the funder’s ethics clearance process (in this case, the ERC) and the Hosting Institution’s review process (here, UCL). The ethics clearance processes within the ERC and the UCL’s REC (Research Ethics Committee) review revealed somewhat similar structural problems. The ethics bureaucracies have been engineered to ensure research ethics particularly due to the appalling track record of research ethics in medical research. These bureaucracies include committee structures, including “lay people” in those committees, “protocols,” and even the very definitions of the “ethical,” all trace their roots from ethics for medical research. This results in the domination medical bias in research ethics (Fisher and Anushko 2008). The disparity between the needs of a particular type of research and the bureaucratic structures built around the needs of medical research ethics often becomes a complicated, exhaustive, and not necessarily ethical process. Below, I will explain the nine ethics reviews requested by the ERC, followed by the hosting institution’s Research Ethics Committee’s three rounds of review processes and nine ethics reports, all of which took place over the course of eighteen months.

ERC Ethics Clearance Process (September 2019 – May 2020): This stage, called “ethics clearance for grant signature”, meant that neither the funder nor the beneficiaries would sign the grant agreement before the completion of the clearance. Since this is before the start of the project, the completion of this clearance is the PI’s responsibility, and it has to take place before receiving the grant. I was not different from several Starting Grant recipients, who received the grant while still under temporary contracts. Like me, they became dependent on the grant agreement to extend or guarantee employment. At that stage, the level of precarity I experienced emotionally and mentally was not comparable to any of the stages of precarities I had experienced throughout my entire career. People from similar class and ethnic backgrounds as me would remember how anxiety-triggering it was between the moment they learned they “got the job” and actually signed the contract, and loaded with “what if.” What if it all fell apart, the funder retracts the fund, and something unexpected happens? It all boils down to not us and our emotional strength but the fact that academia as an institution is more prone to remind people like us that we don’t fit in. This process took eight months for me. Another added emotional burden was the responsibility to the project members, who were also dependent on the project. Most importantly, all this emotional burden was due to legal reasons. The grant agreements cannot be signed before the completion of the ethics clearance which appears to be more about legal obligations than ensuring research ethics.

What if it all fell apart, the funder retracts the fund, and something unexpected happens?

The project had two elements that resulted in the project being categorised for a close ethics review process: (1) the project was focusing on populist forms of Islamism, that I refer to as the I-word, and (2) its implementation across nearly a dozen non-EU countries. Although the concerns were acceptable, the close ethics review process can easily behave differently for different projects. Once a project is flagged for a close ethics review, every ethics component has to be evaluated, including the irrelevant ones. For example, I was required to address the committee members’ concerns, with each category having numerous sub-elements, totalling thirty-three requirements that needed to be explained for each country involved. Highlighted subcategories were human participants’ in the research, protection of personal data, each of the non-EU country’s involvement or lack thereof to GDPR needed to be studied and documented, data transfer (from non-EU to EU), unexpected findings, and data misuse. The entire process is obviously too daunting and detailed to describe here, but I will provide one example for clarification.

Typically, the researcher submits the Information Sheets and the Consent Forms in English to the committee and explains that they will be translated into local languages. In the case of the project, there were nine languages: Arabic, Albanian, Macedonian, Bosnian, Turkish, Farsi, Bengali, Urdu, and Hindi. Unlike the sole mention of their future translation into local languages, I was asked to submit these translations in advance. This request was supposedly aimed at demonstrating my ability to carry out this project, even though my ability had formerly approved by the scientific committee. Every minor edit requested meant additional work, requiring changes to each one of the nine translated text and involving approximately seventy additional hours of effort, including frequent consultations with relevant experts. These alterations would have taken only a few hours if the initial response of the “the final forms will be translated into local languages” had been accepted. However, the ethics committee insisted on reviewing the final translated version two years before the fieldwork start date. After nine such revisions, I received the approval to launch the project, which allowed us to sign the contract with the hosting institution. As is also typical, the ERC Ethics clearance required an internal ethics review by each beneficiary after the project was launched.

UCL Research Ethics Committee (July 2020 – February 2021): Although the ethics bureaucracies shared parallels between the ERC and UCL REC, a different set of anxieties was prompted. UCL’s REC oversees the entire university’s ethics reviews, which are comprise a more significant proportion of members specialising in biomedical research. The REC ethics review process uses different forms, posing similar questions but expecting answers in a different structure, meaning that copy-pasting is not a smart option.

The REC stated that with five researchers in eleven countries, it “is not possible to review the project as a block.” Therefore, they deemed it appropriate for me to submit separate ethics applications for each country. I negotiated this request into separate applications for each work package. I then submitted four more ethics reports and revised each one more time, totalling nine ethics submissions by February 2021. As a result, we have spent hundreds of hours of work, many of which were less about ensuring that we will conduct ethical research, and more about satisfying the particular demands of different ethics panels.

Ethics of Ethnography

One recurring issue underneath several clarification requests was a lack of expertise of the ethics committee members’ in the intricacies of ethnographic field research. Often coming from medical and scientific research backgrounds, the committees are generally more familiar, and experienced in evaluating human research conducted in a controlled lab environment. At this point, consent around participant-observation for instance, becomes blurry. As this was an issue shared by other fellow anthropologists, Ron Iphofen (2016) created an ethics guideline for EU researchers, which I have used in detail. I could respond to the committee’s queries on problems of asking for written consent while conducting participant observation, or what snowballing is and how that is the most fitting research strategy (Iphone 2016: 32). Requesting written consent from every individual who may be part of this participant observation methodology would be simply impossible for two reasons: 1) the entire field research time would be spent negotiating consent forms, and 2) more importantly, a large majority of the people we are working with, and focusing on, have strong suspicions against providing any written proof – let alone their signatures1.

Components such as unexpected findings, misuse, or the researcher’s safety risks were not entirely based on realistic risks, but risks determined by non-experts whose risk calculations were frequently based on stereotypes more than realities.

Imagining the Global South

Components such as unexpected findings, misuse, or the researcher’s safety risks were not entirely based on realistic risks, but risks determined by non-experts whose risk calculations were frequently based on stereotypes more than realities. Media-fuelled stereotypes were apparent both in the committee’s expectations and their lack of detailed protocols for contexts such as North Macedonia, a country that is less known to Western imaginaries.

It is one of the requirements of ethics committees to have a layperson on the committee, a practice that I have found to be highly problematic in social science research conducted in certain geographies that are imagined with Eurocentric prejudices. While the research taking place in the Balkans received next-to-zero additional comments, we received surprising comments and requests to develop protocols on “highly unlikely” possibilities. For example, witnessing human trafficking and child marriage in Pakistan, drug trafficking in Afghanistan, and almost every stereotype that may be prompted in the committee conversations about the region(s). These parts were often in the ethics category “unexpected findings.” After an initial five-page long response, I had already provided explanations about unexpected findings in five categories. One of these categories was “incriminating acts.” Under this sub-category I was expected to come up with diverse crimes the team may come across in each country. For each country and each potential incriminating act we may witness, I had to find a separate NGO specialised on that crime in the respective country. Repeatedly, we were made aware that there was a strong fear about terrorism, despite our interest being in more mainstream forms of populist Islam, rather than extremist forms. The real challenge for me was to indulge very stereotypical perspectives that I had been fighting against, with dozens of hours of labour. To me, that is added labour on the shoulders of scholars like us: even when you develop a creative project, you still need to spend valuable time and energy on the same, reductionist stereotypes levied at your native space and people.

The second challenge that is shared with scholars working on the Global South would be the fact that very few of these queries reflect the actual risks, actual unexpected findings, and actual problems we would face in the field. Not one single ethics board asked us to prepare, for instance, for the sanctions imposed on Iran. While they were insisting that we get insurance, no one was able to even reflect on the fact that over 99% of the travel insurers would not cover Iran. Sexual harassment was not asked either, and we had to prepare for that. This meant that we had to prepare for actual problems, and simultaneously respond to unrealistic risks. The level of burden this caused on myself and my team members was indescribable.

The Elephant in the Room: Nativeness

One unspoken element that has been intensifying the entire experience, that I have been perfectly aware of, was the fact that all of the researchers on my team were from the very societies they had gained expertise on. This unique positionality offers an exceptional ethnographic eye that cannot be taught in a formal setting. Yet, this very unique quality seems to have prompted further interrogations around knowledge, expertise, and professionalism. Amongst many, here is a selected example: One of the ethics queries was for the researchers to explain their interview and other research locations to which we listed a long list of possibilities, one of which was “in public areas where we will not be overheard”. The reviewer singled out this possibility and raised a note suggesting it sounded unprofessional.

Up until that moment, we had noted other occasions on which it was felt clarification requests by the ethics committee were not necessarily strengthening the project from the ethical points, and instead questioning the research team’s expertise and at times even training them. In this particularly egregious case, I could no longer ignore the obvious problem of attitude. To this, I responded directly that although our diverse strategies may sound unprofessional to an untrained eye, in certain contexts including Iran where individuals from opposite sexes are legally banned from being in the same private space, our strategies come from decades of expertise.

Another result of this is an increased administrative workload, considerably higher than any other ethics processes my anthropologist colleagues managing large projects have gone through, including those with projects in the Global South. I had been using their ethics submissions as a template when developing mine. Some of the ethics reports I used belonged to projects with work packages with an actual focus on mental health or refugees (neither of which were included in my work). Yet, I was still expected to respond to dozens of additional notes, clarifications, protocols, and other information that were either not asked of my Western colleagues or only briefly requested.

Ethnographic field research involves additional complexities and needs due to several elements, including the intimate rapport required for ethnographic field research which is often “untranslatable” to the particular language expected in research ethics forms

Conclusion:

This article examined the ethics review processes imposed on a project PI by institutional ethics committees. While sharing my experience I tried to limit my notes to four primary concerns: 1) The challenges arising from media-fuelled stereotypes about certain geographical areas, 2) additional inquiries questioning the expertise of native scholars, 3) the ethical implications of additional administrative tasks and their impact on our workload, and 4) strategies for modifying language to highlight the valuable perspective and extensive knowledge of native scholars in their respective areas of expertise. Social scientists have addressed the unethical aspects of ethics processes and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). Kevin D. Haggerty famously referred to the ethic protocols’ effect on research as harmful and deemed it “ethics creep” (Haggerty 2004).

A long line of social scientists rightfully addressed this as a problem of centralising medical research ethics in review processes (Fisher and Anushko 2008; Haggerty 2004; Hedgecoe 2008; Israel 2014; Lederman 2006), including protocol requirements and committee structures. In our case, ethnographic research conducted by scholars from the geographies they have expertise on was two additional dimensions furthering the complexities and weighting on the team members. Ethnographic field research involves additional complexities and needs due to several elements, including the intimate rapport required for ethnographic field research which is often “untranslatable” to the particular language expected in research ethics forms, (Bell 2014; Bradburd 2006; Librett and Perrone 2010; Metro 2014; Moors 2019; Wynn 2011).

Ethics clearance is often perceived essential to research (and indeed it is). However, our journey was significantly more tiresome. One of the common issues in ethics committees is the requirement to have a “layperson” as an external member. This is a principle introduced in ethical practices in medical research in which a layperson designates a person without scientific knowledge. The idea is that the layperson will empathise with research participants who may sometimes be experimented on. I learned from the discussed experiences that this practice is not ethical when social science research occurs in a non-Western context. Laypersons carry prejudices shaped by media narratives. They will drag the focus of ethics review processes away from actual ethical challenges that may occur during and after the research.

I also introduced the question of “nativeness” into the conversation as an added struggle, as experienced by myself, my team members, and numerous colleagues. International ethics protocols often fail to acknowledge the expertise of native scholars, which is not easy to translate into international ethics protocol language. The researchers in the Takhayyul team explore this point in other parts of this thread on academic methods and fieldwork in the Global South.

Acknowledgements: This publication is part of the ERC StG 2019 TAKHAYYUL Project (853230). I would like to thank Fatemeh Sadeghi, Mezna Qato, Samet Shabani, Layli Uddin, and James Caron. They have all helped me in the process, by doing or reviewing translations, with data collection and data transfer regulations in the countries they were working on. The project is currently under continuous ethics reporting. Every 18 months, I provide the Advisory Board with ethics updates, which they mention in their reports. I upload their reports to the project’s EU portal. I thank the Advisory Board Members, especially Samuli Schielke and Humeira Iqtidar, as they have proven to have an outstanding understanding of my challenges. Their readiness to provide support is invaluable. It was their report that pointed out the excessive burden on me and my team, which prompted the ERC to reduce the number of reports that were expected in continuous reporting. I also thank Laurence Tavernier, the ethics monitoring officer, for providing anchoring support throughout this process.

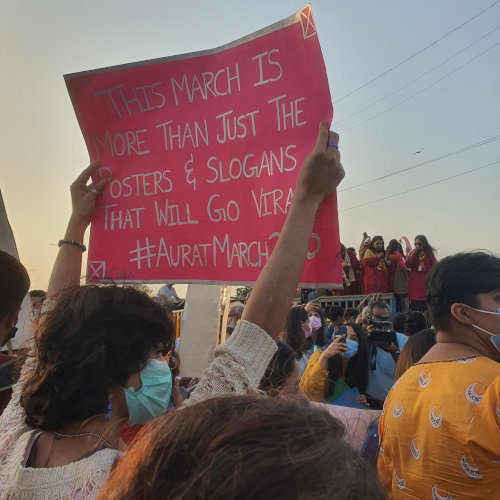

Photo credit: March 8th Women’s Day March, Karachi, Pakistan, 2002 (Photo by the author).

References

Bell, Kirsten. 2014 Resisting commensurability: Against informed consent as an anthropological virtue. American Anthropologist 116(3):511-522.

Bradburd, Daniel. 2006 Fuzzy boundaries and hard rules: unfunded research and the IRB. American ethnologist 33(4):492-498.

Fisher, Celia B, and Andrea E Anushko. 2008 Research ethics in social science. The SAGE handbook of social research methods:95-109.

Haggerty, Kevin D. 2004 Ethics creep: Governing social science research in the name of ethics. Qualitative sociology 27:391-414.

Hedgecoe, Adam. 2008 Research ethics review and the sociological research relationship. Sociology 42(5):873-886.

Iphofen, Ron. 2016 Research ethics in ethnography/anthropology. European Commission, DG Research and Innovation.

Israel, Mark. 2014 Research ethics and integrity for social scientists: Beyond regulatory compliance. Research Ethics and Integrity for Social scientists:1-264.

Lederman, Rena. 2006 The perils of working at home: IRB “mission creep” as context and content for an ethnography of disciplinary knowledges. American ethnologist 33(4):482-491.

Librett, Mitch, and Dina Perrone. 2010 Apples and oranges: ethnography and the IRB. Qualitative research 10(6):729-747.

Metro, Rosalie. 2014 From the form to the face to face: IRBs, ethnographic researchers, and human subjects translate consent. Anthropology & education quarterly 45(2):167-184.

Moors, Annelies. 2019 The trouble with transparency: Reconnecting ethics, integrity, epistemology, and power. Ethnography 20(2):149-169.

Sehlikoglu, Sertaç. 2024 Imaginative landscapes of Islamist politics: An introduction to the heuristic concept takhayyul. History and anthropology Online First.

Wynn, Lisa L. 2011 Ethnographers’ experiences of institutional ethics oversight: Results from a quantitative and qualitative survey. Journal of policy history 23(1):94-114.

Abstract: Reviewing the Takhayyul Team’s long journey of ethics approvals by various institutional bodies, this paper questions the ethics of such protocols for native scholars. It questions several issues formerly addressed by anthropologists, highlighting the intimate rapport required for ethnographic field research to be ‘untranslatable’ into the particular language often expected in research ethics forms. Following written conversations between the institutional ethics committees and the team members’ reports, it then reflects on the limits of research ethics and questions those limits in relation to the nativeness of the researcher and conducting research in the Global South.