In the wake of calls for responsibility and for ‘Raising our voice’ (AAA 2020), early-career researchers’ in anthropology risk to bear the weight to redeem the discipline while struggling in the bounded condition of generational precarity. Moving from a roundtable held at the ASA conference in February 2021, this thematic thread explores forms of precarity lived and witnessed in the field, reflecting on the challenges and opportunities they present to anthropology’s epistemic crisis. More and more, ethnographers find themselves caught in a double bind. On the one side, during the last decades a majority of anthropologists have been focusing on power, domination, inequality, and oppression (Ortner 2016). On the other side, in the hyper-productivity of the ‘publish or perish’, they are urged to transform ‘the affective interiority of ethnographic subjects’ into material for the strenuous and self-exploitative academic competition’ (Jobson 2020: 266). Even when (post)colonial reflexivities are formally encouraged in liberal and progressive — but still predominantly white — anthropology departments, early career researchers find themselves struggling to get short-term, unprotected contracts, while being pushed to bracket any solidarity-based ethos by the highly individualizing politics of authorship and knowledge production of the shrinking academic market. At the same time, they are asked to elegantly solve these contradictions and ‘save’ the discipline from its epistemological crisis as a Western intellectual project.

Against this background, the texts reproduced here critically engage with a specific triangulation happening in contemporary anthropology: the shrinking of academic employment; the political and epistemic crisis of (European) anthropology; precarity as a generational condition affecting both ethnographers and research participants. Dialoguing with the EASA Report ‘The anthropological career in Europe’ (Fotta, Ivancheva & Pernes, 2020), this collection of texts interrogates the pitfalls, struggles, challenges as well as opportunities arising from such configuration. In doing so, far from uniforming experiences in the name of a generational proximity flattening global inequalities, the textual and graphic pieces engage with the multiple and asymmetrical forms of precarisation and vulnerabilisation involving both ethnographers and their interlocutors in and beyond the field. As a whole, they address the following main questions: if precarity is ‘the multiple forms of nightmarish dispossession and injury that our age entails’ (Muehlebach 2013: 298), what does it mean for precarious anthropologists to be subjected and, at the same time, to bear witness of its various degrees of dispossession? What kind of knowledge and political subjectivities emerge and are produced in the process? How is the ethnographer’s own positionality filtered, modelled and potentially silenced by the standards regulating academic knowledge production?

Starting from these interrogatives, the thematic thread moves beyond the (fundamental) discussion of academic precarity in the field of anthropology (Ivancheva 2016) to engage in a discussion in which this is put into relation with the dynamics of fieldwork. As such, the contributions claim the multiple precarities lived and witnessed in the field and what we define as ‘spurious solidarities’ as relevant analytical lenses to illuminate the topsy-turvy and porous politics of ethnography. From this stance, we deal with ambiguous proximities between the ethnographer and her interlocutors: in experiencing the economic crisis of Southern Europe (Letizia Bonanno); in the cross-fertilization between academic spaces, self-organised migrants and everyday struggles (Ioanna Manoussaki-Adamopoulou); in the partial connections between neoliberal academic ethos and moral economies of wrestling in Senegal (Francesco Fanoli); in the existential proximities and radical inequalities in the quest for adulthood through geographical mobility (Viola Castellano); in the emergence of potential spaces in which the vulnerabilities and potentialities related to motherhood can be shared and mobilised (Olivia Casagrande). How can these ethnographic encounters help anthropologists to critically approach mechanisms of silencing engrained in anthropological research, as well as forms of self-exploitation, hyper-competitiveness and production to which they subject themselves in order to survive in academia and which end up reproducing the same power structures (Allegra Lab 2022)?

The messiness of ethnography, the relational fabric it engenders, the forms of counterintuitive recognition between ethnographers and their interlocutors, rather than constitute sub-products of the analytical commodity of which anthropologists can claim exclusive ownership, need, in our opinion, to be interrogated critically as part of the epistemic and political praxis of an increasingly precaritised anthropology (Backe 2018). The elaborations on these asymmetries and ‘spurious solidarities’ thus develop a reflection on the impossibility of the ‘liberal myth of perfectibility’ (see Brodkin, Morgen, and Hutchinson 2011), rather arguing for taking seriously and ‘staying with’ (Haraway 2016) issues connected to the controversial status of anthropology in current times. We argue that thinking through partially shared precarities and their epistemological significance could be a way to interrogate more deeply researchers’ positionality, the conditions of production of knowledge in the anthropological field and the political practices and subjectivities emerging at the intersection of our discussion.

References

Backe, Emma Louise. June 2018. ‘Personalizing Access, Personalizing Praxis’. Allegra Lab. https://allegralaboratory.net/personalizing-access-personalizing-praxis-hautalk/

Brodkin, Karen, Sandra Morgen, and Janis Hutchinson. 2011. “Anthropology as white public space?.” American anthropologist 113, no. 4: 545-556.

February 2022. ‘On the use and abuse of networks in academia’. Allegra Lab. https://allegralaboratory.net/on-the-use-and-abuse-of-networks-in-academia/

Fotta, Martin, Mariya Ivancheva, and Raluca Pernes. 2020, “The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey.”European Association for Social Anthropologists

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press,

Ivancheva, Mariya. February 2016. ‘The Neoliberal Race to the Bottom Affects Us All!*’. Allegra Lab. https://allegralaboratory.net/anthropologists-are-not-immune-from-the-neoliberal-race-to-the-bottom/

Jobson, Ryan Cecil. 2020. “The case for letting anthropology burn: Sociocultural anthropology in 2019.” American Anthropologist 122, no. 2: 259-271.

Muehlebach, Andrea. 2013. “On precariousness and the ethical imagination: the year 2012 in sociocultural anthropology.” American anthropologist 115, no. 2: 297-311.

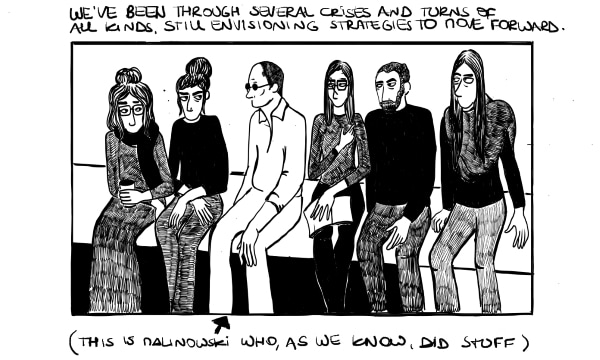

Featured image by Letizia Bonanno