This thematic thread gathers together a series of posts by leading experts and anthropologists of Afghanistan, who analyse the 2014 Afghan presidential elections and their consequences for the future of the country.

2014 is supposed to mark the withdrawal of the NATO troops. It is therefore the right moment to draw some conclusions and assess the achievements of 10 years of international intervention and military occupation.

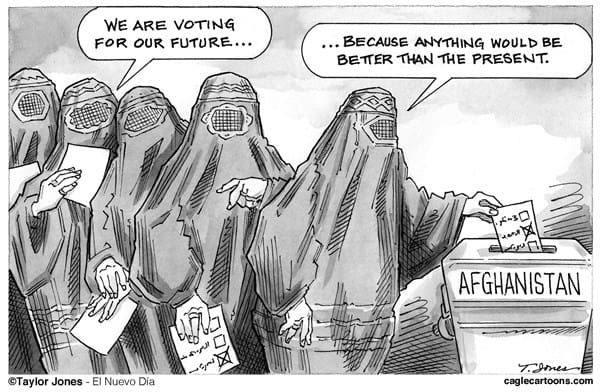

Reading the media coverage of the presidential elections over the past months, one cannot help but notice the disconnect between the narratives of ‘democracy building’ that have accompanied the invasion of Afghanistan, and the increasing level of violence Afghans are witnessing on a daily basis. Images of voters having their fingers cut and suicide attacks remind us that the correlation between elections and democracy is far from being self-evident.

Reading the media coverage of the presidential elections over the past months, one cannot help but notice the disconnect between the narratives of ‘democracy building’ that have accompanied the invasion of Afghanistan, and the increasing level of violence Afghans are witnessing on a daily basis. Images of voters having their fingers cut and suicide attacks remind us that the correlation between elections and democracy is far from being self-evident.

Unlike the refugee camp seen as emblematic of the “state of exception”, from the outset the process of “reconstruction” in Afghanistan was presented as a moment of return to normality or “normalization” after many years of war and authoritarianism [1]. This discourse, together with the regular organisation of democratic rituals such as elections, have fueled the illusion of a radical shift from an old order perceived as barbarian to a new democratic order. However, the inconsistencies and ambiguities of the “reconstruction” force us to understand such electoral performances as a form of carnivalesque expression in the sense of Bakhtin, aiming at bolstering the idea of change and progress for the Western audience while strengthening structural hierarchies at the local level [2]. Indeed, the very establishment of the Afghan humanitarian theater heavily relied on the mise-en-scène of “distant suffering” [3] by Western media and the introduction of arguments based on pity (especially towards women), freedom and human rights to justify the military occupation of the country. However, in the absence of material improvements in the lives of most Afghans, and with the return of warlords in power, Afghans have been forced to improvise various strategies to try and maintain a sense of continuity. The contradictions inherent to externally imposed emancipatory projects have fuelled popular sentiments of alienation, condemning Afghans to remain “prisoners of freedom”, to use the title of Harri Englund’s famous book [4].

In the first installment of this thread, Nichola Khan provides an overview of the various forces at play in the Afghan political arena. She rightly reminds us that ‘violence works: not in achieving the institution of democracy (which would involve Taliban representation), but in forcing the redistribution of power in violent, perceptibly just terms that are far from transformative, but deeply conventional’.

Anna Larson questions the extent to which liberal understandings of democracy can be applied to the Afghan context. Building on Charles Tilly’s democratisation theory according to which democracy building primarily relies on the capacity of the state and citizens to develop ‘functioning’ relationships, she questions the usefulness of such categories (state, citizen) to describe the Afghan political environment. In her view, such misguided conceptualisations and the disregard for local configurations of power have largely contributed to the failure of the ‘democracy building’ project in Afghanistan.

Noah Coburn’s ethnographic exploration of the electoral process leads him to similar conclusions: “The international intervention, he argues, has cumulatively contributed to the destabilization of Afghanistan, and the widening of the gap between the government and the Afghan people”.

We conclude the thread by two posts by Antonio De Lauri and Niklaus Miszak, providing broader reflection on the values and ideologies that guide ‘democracy building’ exercises. De Lauri demonstrates how the ideology of ‘hope’, in Afghanistan like in Italy, has been used as a powerful ersatz against civic engagement and meaningful political action. Along the same lines, Miszak argues that the campaign was sold to the public in purely technical terms, as a means to ‘domesticate violence’, with no genuine attempt at triggering deeper political debate on the future of the country. Ironically, violence has not been domesticated and the threat of war is each day more present as presidential candidates continue their fight for capturing power.

References

[1] Antonio De Lauri & Julie Billaud, « Humanitarian Theatre: The Ordinary and the Carnivalesque in Afghanistan », in The Politics of Human Rights: Security, Aid and the Hidden Agendas of Humanitarianism, éd. par Antonio De Lauri, I.B. Tauris, 2015 (forthcoming).

[2] Julie Billaud, Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in « Post-war » Afghanistan, University of Pennsylvania Press, The Ethnography of Political Violence, 2015 (forthcoming).

[3] Luc Boltanski, La souffrance à distance: morale humanitaire, médias et politique (Editions Métailié, 1993).

[4] Harri Englund, Prisoners of freedom: human rights and the African poor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).