Urgency and Transition

Environmentalism is rhetorically framed as a “Good Thing”, unquestionably. Being environmentally friendly is, as it were, a no-brainer. Anthropologists have shown many times however, that what constitutes good environmentalism can be flawed vis-a-vis other ontologies or even contradictory to seemingly compatible beliefs. As an example of the former, Rival (2006) has shown in the Ecuadorian Amazon that conservation programmes that begin with the premise of pristine forest environment have totally disregarded a landscape history shaped by generations of Huaorani trekking groups subsisting in, and indeed cultivating the forest flora. Exemplifying the latter, a five pence tax on disposable carrier bags implemented in shops in Wales, UK was donated by one retailer to a charity whose conservation programmes included a widespread cull of grey squirrels, considered a “non-native” species. How to make sense of such a variety of interventions made under the banner of “The Environment”?

Alexander (2005) points out that sustainability is “a potent but empty rallying cry”, it is a concept laden with value but perhaps skimpy on precise details, producing a rise in “greenwashing” as a corporate marketing device. Claims to environmentalism therefore warrant scrutiny.

At a moment in which the sense of human-derived environmental chaos, captured by the term “the Anthropocene”, has become highly palpable, the question of transition has emerged with growing urgency.

This urgency, if not checked, risks intensifying the colonial politics of environmentalism. This essay seeks to decolonise environmentalism, by situating environmentalism in dialogue with other modes of human-more than human relations.

The idea of “transition” frames the significant changes to climate, resource use and energo-social relations that have occurred and which still need to happen to avert environmental catastrophe, such as that detailed in this recent IPCC report. In energy terms, transition is broadly taken to mean the transition from heavy reliance on fossil fuels to greater everyday use of renewable energy resources from domestic to industrial and transport uses.

This essay looks at the transition movement in broad terms, above all as embodied in Transition Town initiatives, but with a particular focus on green lifestyle migration informed by my research in west Wales, UK.

Planning for the Future

I have conducted ethnographic research in rural west Wales since 2010 and examined ecovillages and households that choose to live off the grid and an emergent policy context (One Planet Development/ OPD, 2010) which positions living off grid as a viable zero-carbon development model. Living off grid is a practice that can be seen as part of a new wave of the back to the land movement and is very definitely situated in the transition movement (Forde, 2015; 2017). Off-grid dwellings were usually built in remote locations without planning permission particularly prior to the OPD policy.

The planning policy “One Planet Development” (OPD) has been developed by the devolved Welsh Government as part of its 2009 Sustainability Strategy “One Wales One Planet” (2009). The OPD development model relaxes planning restrictions in open countryside for demonstrably zero-carbon smallholdings and as such encourages Green lifestyle migration to rural areas. The first of its kind in the UK, OPD attracts people from across the globe.

West Wales and Green Lifestyle Migration

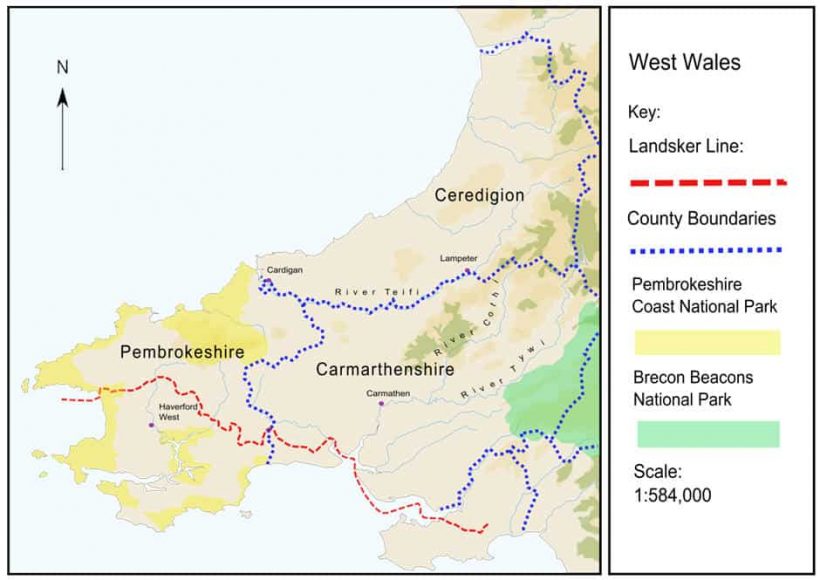

West Wales is a rural region characterised by pastoral farming in small, predominantly family farms, dotted across verdant undulating valleys. Welsh farmers sometimes describe their land as “ddaear” (ground), the relatively small parcels the result of an historic system of partible inheritance so that holdings contain the history both of family and of ground. The region doesn’t precisely map onto any administrative region, and over the years I have come to realise that west Wales is more of a feeling than a rigidly defined place. West Wales is predominantly a Welsh speaking area, Y Fro Cymraeg, where most peoples’ preferred everyday language is Cymraeg (Welsh). Yet after any amount of time spent in the area it becomes apparent that there is a significant English-speaking population concentrated in and around the rural hinterland, something Janice Williams (2003) picked up on in the mid-1990s and which she termed “alternatives”.

While the English have a long history in Wales, the 1960s saw the beginnings of an influx of holiday-makers and second-home owners. Several decades on, and as Gallent et. al. (2003) have shown, second homes are less the controversy they once were, whereas green lifestyle migration is becoming a more significant, and in some respects more controversial, form of migration.

Michaela Benson examines lifestyle migration in her work on rural France. This is the British/English search for a better quality of life abroad. I have adapted the term from Benson, and use “Green” lifestyle migration to describe the similar process in rural Wales. The aspiration to have a “better” life is shared; in the latter case however, a commitment to environmentalism appears to be the primary motivating factor.

This wave of green lifestyle migration has seen people and groups moving to rural Wales to go back to the land since at least the 1970s. The author John Seymour was perhaps foundational in the movement. Arguably it was Seymour’s own family’s move from a small holding in Suffolk to a small farm in west Wales (North Pembrokeshire in fact)—as documented in The Fat of the Land (1974)—that inspired the fascination with, or at least perception of, West Wales as a haven for back to the landers, a source of cheap but expansive rural property, and a place where “the locals” were still farming in a traditional way. As such the region supports a number of ecovillages, off grid dwellings and other people and projects in a network of sites pursuing environmental and ecological transition, from permaculture farms to housing co-ops. It is no surprise that planning policy would eventually develop a response to support and regulate this kind of development.

Jenkins’ fascinating 1971 ethnography of a west Wales farming community juxtaposes the oral histories of old timers with contemporary observations to document over a century of changes in the west Wales agriculture scene. Published in the early 1970s, in the same period as Seymour’s books, Jenkins offers an alternative portrayal of the socio-economic context.

Far from the idyllic communism of shared labour at harvest-time that Seymour describes, or the Anglicised romanticism of the “village” that so many back to the land projects in Wales emulate (without irony), Jenkins outlines the systems of indentured labour that saw isolated farms support multiple households as retainers in hereditary positions held for generations.

In Jenkins, the farm is a socio-economic unit of production that ties multiple actors together in complex relationships with each other and the ground itself.

Using these texts, and my own observations and participation, it has been possible for me to draw comparisons between the contemporary back to the land movement in Wales and the rural “traditions” that are central to how going “back” to the land is imagined. What emerges is a composite environmentalist discourse based on a relationship between transition and tradition.

Transition Narratives

Simple historical-to-contemporary comparisons neither push the frameworks for social analysis nor critique practice in unexpected ways, therefore I suggest using a lens of settler colonialism to understand the issues at play. According to Veracini (2010), settlers differ from other migrants as they “‘remove’ to establish a better polity, either by setting up an ideal social body or by constituting an exemplary model of social organization” (ibid, 4. My emphasis). While there is no overt racial discourse in this context, the idealised notion of an OPD settlement is contentious.

As a dominant ideology, environmentalism silences alternative views and stifles negotiation, and as such is hard to challenge. Some ethnographic examples may help to illustrate the problem.

Most puzzling to my informants has been the coupling of in-migration to West Wales with the desire to change the area, symbolised by a crop of Transition Groups and Initiatives.

To avail of OPD planning permission, applicants must submit to a number of reporting exercises to demonstrate the use-value of their development. In an early publication outlining Lammas’ “Aims and Intentions” (2009), one resident described the economic potential of the site’s transformation, from a regime of sheep monoculture grossing £2,500 per annum to a productive permaculture-inspired village producing over £100,000 worth of abundance, from fruit to smoked hams, from baskets to educational experiences (ibid: 34-35).

A history is elided by this narrative, however. I learned later on that prior to its sale in the 1970s, (after which the farm had been sold off in smaller lots of fields and buildings, one parcel to become the Lammas ecovillage), the farm held the biggest milk quota in Wales. This had been an immensely productive dairy farm, the decline of which told the story, not only of in and out migration, but family, state, policy and ground.

On one occasion in 2011 I attended a guided tour of the new Lammas Ecovillage in Pembrokeshire. the UK’s first fully legal, fully lawful and fully planned ecovillage. This place had been a milestone for advocacy for low impact development in Welsh planning policy and one of the subjects of my doctoral research. We were a mixed bunch of people on the tour. City families looking for something new, old hippies, knowledgeable “types” coming for a look, even a local farm woman who shared several raised eyebrows with me as we heard about outlandish ways to grow strawberry crops on shale banks.

This was a blustery, bright spring day in North Pembrokeshire, at the foothills of the impressive Preselis, and we were lucky they weren’t shrouded in mist as they usually tend to be. It truly was a glorious day. Our gaggle of tourists started milling around and at this point our guide gestured lazily across the valley as she outlined her vision for how the Lammas model would change the world.

“Just look at that empty blandscape over there. Now imagine 10 or more eco-smallholdings dotted about with busy families all living and working on the land. That’s what Lammas wants to inspire”.

Inspired, but in a way other than intended, a local farm woman protested: “It’s NOT empty, it’s beautiful!”

These two competing perceptions of the very same view exemplify how the colonial concept of Terra Nullius functions. On one hand a local woman and neighbour of the village, saw the landscape as intrinsically full, of beauty, of memory and history; on the other, a settler, saw potential, a blank canvas, an empty “blandscape”, or (another favourite term to critique agribusiness) a Green Desert. The concept of “busy families working the land” evokes a labour theory of value in which visible “work” produces value and less tangible forms of occupation do not.

What is more, the critique of agri-business is not simply external, many farmers express the uncomfortable knowledge that their industry is both unsustainable and insecure. Overstretched, undervalued and uncertain, Welsh agriculture under the looming shadow of Brexit is not a happy place to be. But using the notion of consubstantiation (Halfacree, 2007), referring to a belonging to and constituting of the land, a farmer’s ground is not simply their piece of land: it is them, they take the name of their farm, they become they belong and are grounded there. The value of land can therefore not be modelled in purely economic or environmental terms.

Conclusion

Recent growth in scale and speed in the Back to the Land Movement in Wales has invited this critique of green lifestyle migration and the policy frameworks that support transition. This is not a critique of migration and free movement; when viewed simply as the desire to put a low-carbon future into practice now, a policy such as OPD seems outwardly benign at least. There is a need, however to decolonise environmental discourse, particularly when it borrows its tools from colonial discourses.

Examining patterns of settlement in rural Wales using settler colonial theory is controversial, yet some commonalities are too consistent to ignore. The actions of “pioneer” groups and the premise of Terra Nullius are crucial here, and are a consistent feature of new transition narratives.

While some landscape histories may be unknown, others are elided by common transition narratives which are finding new traction in environmentalist policy initiatives.

The complex intertwining contradictions between, on the one hand, belonging, localism and consubstantiation, and on the other, the ideology of environmentalism, the desire to change, transition and improve to meet the urgency of anthropogenic climate change, highlight the importance of the question “whose green?”. OPD policy prioritises an environmental-economic rationale over other notions about the land and environment. This rationale perhaps comes easier to green lifestyle migrants than it does to the extant rural population in Wales.

What is particularly remarkable about this case study is that the OPD planning policy was devised by the devolved Welsh Assembly Government. The coupling of this policy to an extant in-migration trend has become a potent evocation of settler colonialism, but is not a politically external imposition.

Postscript: Decolonising Scholarship

While inspiration comes from many quarters and surely many more acknowledgements are due, certainly to Nina Moeller, my writing mates here and members of the ASA 2018 “Whose Green?” panel at Oxford, my particular gratitude goes to the members of the “Settler Toxicity” panel at Cultures of Energy symposium at Rice, April 2018 for the illuminating discussions about Settler Colonialism and the (surprisingly many) Problems with Environmentalism (Montoya, Simmons and Spice).

References

Alexander, C. (2005) “Value: economic valuations and environmental policy”. In J. G. Carrier (ed.) A handbook of economic anthropology. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 455–470.

Benson, M. (2011). The British in Rural France: Lifestyle Migration and the Ongoing Quest for a Better Way of Life. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719082498

Forde, E.

- Planning as a form of enclosure? The ambiguities of non-productive accumulation in the west Wales countryside. Focaal. No. 72 pp. 84-91.

- The Ethics of Energy Provisioning: Living off-grid in rural Wales. Energy Research and Social Science. (Vol 30. pp.82-93)

Gallent, N. Mace, A. and Tewdwr‐Jones, M. (2003) Dispelling a myth? Second homes in rural Wales. Area. 35(3). Pp. 271-284

Halfacree, K. (2007) “Back-to-the-land in the Twenty-First Century—making connections with rurality”, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 98, pp. 3–8.

Jenkins, D. (1971) The agricultural community in south-west Wales at the turn of the century. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Rival, L. (2006) “Amazonian historical ecologies”. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 12 (Ethnobiology and the science of humankind) pp. S79–S94.

Seymour, J. (1974) The Fat of The Land. London: Faber and Faber.

Veracini, L. (2010). Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Williams, J. (2003) “Vegetarian biographies in time and space: vegetarians and alternatives in Newport, west Wales”. In Davies, C. A. and Jones, S. (eds.) Welsh Communities: New Ethnographic Perspectives. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, pp. 49–79.

Welsh Assembly Government.

(2009) One Wales, One Planet: A new sustainable development scheme for Wales. Available at: http://wales.gov.uk/topics/sustainabledevelopment/publications/onewalesoneplanet/?lang=en (accessed: 24 May 2013).

(2010) Technical Advice Note- Planning for Sustainable Rural Communities. Available at:http://wales.gov.uk/topics/planning/policy/tans/tan6/?lang=en (accessed: 24 May 2013).

Wimbush, P (2009). Lammas: Aims and Intentions. In Pickerill, J and Maxey, L (Eds.). Low Impact Development: The future in our hands. Leeds: Creative Commons. pp. 30-38.

Featured image by Tony Armstrong-Sly (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)