The situation in Myanmar during and shortly after my fieldwork in March 2020 reminded me of the uncertainty of knowledge and call for prudence which started the Allegra corona thread. In the face of possible contagion, my attention was drawn to my own technologically mediated connectedness: In the context of COVID-19, everyday techniques such as payment methods, potentially relevant for transmission, both isolate and connect people. Techniques, understood as ‘effective’ and ‘traditional’ action (Mauss 1973), are crucial to understanding how people are in touch through isolation.

Myanmar in March

The WHO declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. The same day, people in Yangon started stocking up on dry goods, an indication of growing anxiety. The first of my friends went out less, carried disinfectant and talked about social distancing more. They followed global and local news, knew about the measures advocated in several Asian, European and North American countries and by the WHO. They tried to propagate the measures on social media and in their families and sought to re-affirm a semblance of order thrown into doubt by the disease. Two things felt particularly difficult: getting their elders to listen and getting trustworthy information. A friend who remembered the onslaught of cyclone Nargis in 2008 and ensuing empty shelves urged me to stock up as well. Another friend, who feared that unreliable news would spread, promoted a dashboard of social media news on COVID-19 in Myanmar. As we were sitting in an open-air restaurant one night, someone started speculating whether a COVID-19 emergency would lead to a state of emergency. Many I worked with, as well as I, were finding social distancing hard – just as US officials telling people to stop touching their faces had a hard time following their own advice.

On 23 March, the Myanmar Ministry of Health confirmed the first two COVID-19 cases in Myanmar, returnees from the USA and the UK. I decided I had to leave or risk being stranded. I met with friends on the eve of my flight. When I mentioned that the cases so far had been imported, they hesitantly told me about a meme: a picture of a former military leader roughly reading “See, that is why we were xenophobic”. As Myanmar’s head of state, Than Shwe oversaw two decades of isolationism between 1992 and 2011 while maintaining relations with Myanmar’s immediate neighbours (Egreteau and Jagan 2018). There have been speculative arguments whether disaffection for foreign involvement shows in the 2008 constitution’s section 59(f), barring anyone who has immediate foreign relatives from becoming president (Crouch 2020: 117-8), and in the reluctance to accept relief assistance in the aftermath of cyclone Nargis (Stover & Vinck 2008: 730, Seekins 2009: 727). Now, with cases of COVID-19 infections in Euro-America on the rise, another kind of foreign influence, of viruses from abroad using humans as conduits, needed to be stopped.

A meme of former General Than Shwe. The caption reads “I told you about twenty years ago that we have to recognise all those relying on foreign countries as a common potential enemy and crush them.”

Grasping what it takes to pay

On 13 March, during the uncertain times described above, the director-general of the Ministry of the Office of the State Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi’s main ministry as the de-facto leader of Myanmar, gave a press conference (Kyaw Hpone Hma 2020; MNA 2020). The government was preparing for COVID-19 and those spreading ‘fake news’ would be prosecuted, the director-general was quoted.

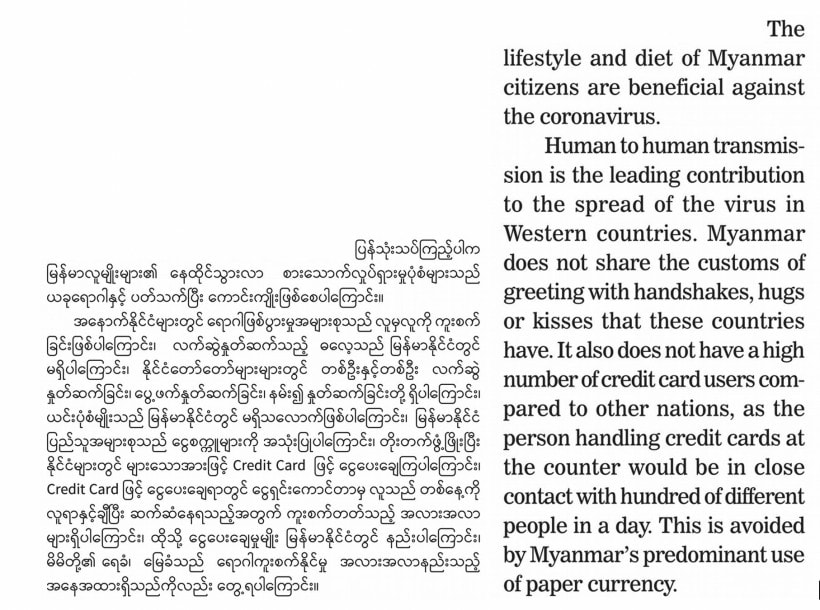

The director-general’s remarks on payment techniques, reported in the government newspapers above, particularly struck me as they contradicted Euro-American articulations. The UK, Germany and allegedly even the WHO assumed contactless payment to be more efficacious in slowing the spread. The director-general was arguing to the contrary. Whereas the Guardian and an international human rights organisation interpreted this as further evidence of the government’s denial of COVID realities, I turn to examining the director-general’s reported remarks from a point of view informed by the anthropology of techniques (see Coupaye and Douny 2009).

The government was preparing for COVID-19 and those spreading ‘fake news’ would be prosecuted, the director-general was quoted.

The anthropology of techniques examines techniques as social. Originating in Marcel Mauss’ work, it understands a technique broadly as “an action which is effective and traditional (and you will see that in this it is no different from a magical, religious or symbolic action)” (Mauss 1973: 75, emphasis in original). Calling a technique traditional, Mauss emphasises that techniques are not solely a matter of individual practice. They are learned and necessitate the involvement of several actors, human and other-than-human (compare Leroi-Gourhan 1993: 25–60). Arguing that efficacy is a quality of techniques, “magical, religious or symbolic” (Mauss 1973: 75), implies that the efficacy of a technique is an open question with various, emic and etic, answers (compare Warnier 2009: 467-8). Jean-Pierre Warnier took the articulation between bodies and persons further, arguing that techniques act upon both subjects and objects (Warnier 2009) as people-as-bodies relate to themselves. Techniques, insofar as they involve bodies, bodily enact who somebody is. As hands touch faces, bodies and other matter, techniques make people.

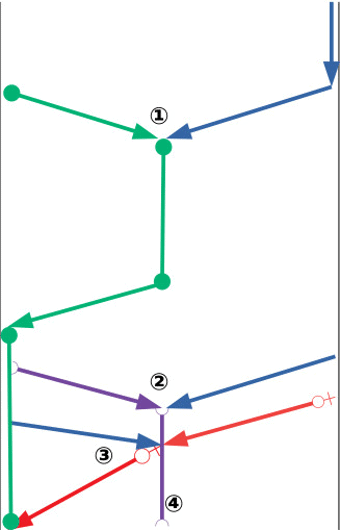

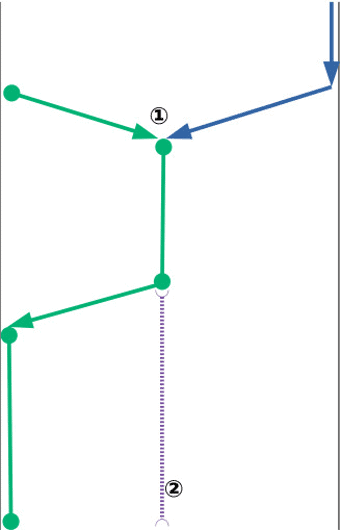

While anthropological engagement with techniques and bodies is far broader, the literature referenced allows suspending the assumption that credit cards are objectively better than cash for keeping the virus at bay as merely one emic articulation. Linking subjects and objects, the anthropology of techniques allows us further to bridge the gap between manual action, e.g. handling money, and technology, e.g. credit cards and credit card readers. Why could cash be more efficacious in preventing the spread of COVID-19 than card payment, according to the director-general? Which techniques might have cashiers be in particularly “close contact with hundred [sic] of different people” (MNA 2020) in card payments, but not with cash? His remarks are sparse and I will have to compliment them with my own observations, illustrated by chaînes opératoires, visualised operational sequences of techniques (compare Lemonnier 1992).

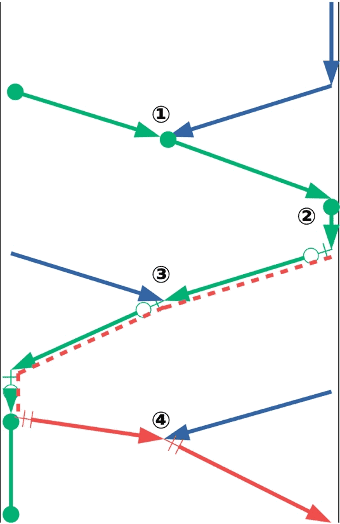

To my initial surprise, when paying by card in Yangon supermarkets, the cashiers usually took the credit card out of my hand over the counter (① in chaîne opératoire 1). After typing the amount into the reader, they put the card on or into it (② in chaîne opératoire 1), prompted me to enter my PIN or, more often, handed me back my card with a receipt and pen (③ in chaîne opératoire 1). I would then sign the receipt and hand it back (④ in chaîne opératoire 1; receipt version depicted only). If I paid in cash, however, I would give money to the cashier (① in chaîne opératoire 2). They would check the amount (② in chaîne opératoire 2), take the change out of the register (③ in chaîne opératoire 2) and hand it over in a neat pile, touching their right arm above the elbow with their left hand, holding the money on the small side, sometimes creasing it in the middle (④ in chaîne opératoire 2). I would take the return (⑤ in chaîne opératoire 2) while the cash given would remain with the cashier.

Taking touch as an index of proximity, the customer and the cashier touch the same thing more often when paying by card than when paying by cash, three times against twice. Additionally, items which change hands in cash payments do not return to the giver. These two factors could qualify the director-general’s description of paying by credit card as closer contact.

As hands touch faces, bodies and other matter, techniques make people.

It is important to note that my articulation is one among many. At the time, I was texting with two local friends and interlocutors. When I wrote that I felt both anxious and that “my lifestyle and diet will protect me”, one said they were also “feeling both. And a bit feverish”, affirming shared anxiety and confidence.

As I spoke with the second interlocutor a few months later, he told me he understood the director-general to have meant that a) the number of contacts in credit card payment was higher because transactions were faster and b) the number of interactions in small local stores which operated by cash would be lower. He further thought the director-general said this to calm people down, not because it was true. My interlocutor thus focused on the supposed effects of the director-general’s words rather those of the actions described. We further diverged on our respective interpretations of what the director-general called ‘close contact’. While the director-general’s words likely did have effects, I delve a bit deeper into physical techniques and contact.

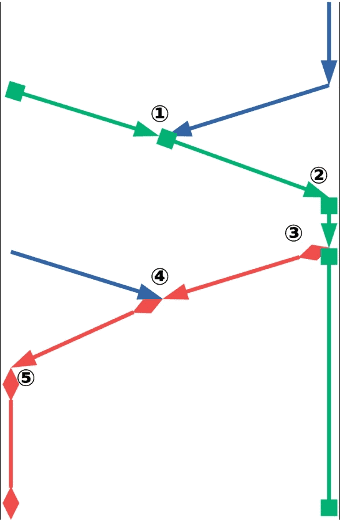

If we apply a similar perspective to another, ‘contactless’ way of paying by card (as in chaînes opératoires 3 & 4), we see two things happen to the contact between customer and cashier. First, points of physical contact are reduced but not eliminated. There still is physical, at least electronic, contact between reader and card (① in chaînes opératoires 3 & 4) so that something from the card can be transferred to the reader and vice versa (④ in chaîne opératoire 3 and ② in chaîne opératoire 4), not to mention shared breathed air. If the customer enters a PIN (② in chaîne opératoire 4) or takes a receipt (③ in chaîne opératoire 4), contact becomes manual. Secondly, contact increasingly happens at a distance as the cue for the card is verbal or visual, given remotely by the cashier (① in chaînes opératoires 3 & 4 and ④ in chaîne opératoire 4). ‘Contactless’ payment is therefore not without contact. Contact, however, is mediated.

Hands off!

The director-general alerts us to a crucial technical issue: How are we in contact with each other and ourselves? We work on ourselves as we wash our hands or refrain from touching our faces. Despite disagreement on its efficacies as examined above, the arguments for and against using credit card payments share a similar aim: Keeping people’s hands off each other. People ought not touch their faces or a stranger’s body. Ideally, in isolating and individuating bodies, those censored acts keep bodies and populations healthy. It seems the time for isolation has come again and many, both locally and internationally, agree now that isolation is necessary to keep germs out. Fears of foreign influence, this time the influx of a virus, is not just a Myanmar issue. Remote contact, like contactless payment, however, increases as contact between potentially-virus-bearing-bodies is reduced. Payment cues become visual and verbal. People use techniques to distribute themselves beyond their bounded bodies (compare Gell 1998: 96–154), like the cashier typing the amount owed into the register connected to the card reader. We read news online or hold video calls. We find ways to stay in touch but are convinced we are not touching. ‘Contactless’ payment requires at least electronic contact between the card and the reader. Yet, its opacity convinces us of its efficacy in keeping us apart (compare Coupaye and Douny 2009: 22).

We find ways to stay in touch but are convinced we are not touching.

If we see ourselves as bodies-with-tools (compare Leroi-Gourhan 1993: 240–42), we realise the ways in which we are connected through what we thought kept us apart. In times when people try to isolate, tools are a vector of danger, potential conduits of germs, as well as means to keep in touch. It is time to grasp who is at our extended fingertips as we touch our cards to the reader, as we hand money to the cashier and to see eye to eye, miles apart.

References

Coupaye, Ludovic, and Laurence Douny. 2009. ‘Dans la Trajectoire des Choses. Comparaison des approches francophones et anglophones contemporaines en anthropologie des techniques’. Techniques & Culture. Revue semestrielle d’anthropologie des techniques, no. 52–53 (December). Les éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’Homme: 12–39. doi:10.4000/tc.4956.

Crouch, Melissa. 2019. The Constitution of Myanmar: A Contextual Analysis. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Egreteau, Renaud, and Larry Jagan. 2018. Back to Old Habits : Isolationism or the Self-Preservation of Burma’s Military Regime. Back to Old Habits : Isolationism or the Self-Preservation of Burma’s Military Regime. Carnets de l’Irasec. Bangkok: Institut de recherche sur l’Asie du Sud-Est contemporaine. http://books.openedition.org/irasec/498

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kyaw Hpone Hma. 2020. ‘နိုင်ငံတော်အတိုင်ပင်ခံရုံးဝန်ကြီးဌာန ညွှန်ကြားရေးမှူးချုပ် ဦးဇော်ဌေး သတင်းမီဒီယာများနှင့်တွေ့ဆုံပြီး CoVID-19 ရောဂါနှင့် ပတ်သက်၍ ကြိုတင်ပြင်ဆင် ဆောင်ရွက်နေမှုအခြေအနေများကို ရှင်းလင်းပြောကြား’. Myanmar Alinn Daily, March 14.

Lemonnier, Pierre. 1992. Elements for an Anthropology of Technology. Anthropological Papers 88. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Press.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. (1964) 1993. Gesture and Speech. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Mauss, Marcel. (1935) 1973. ‘Techniques of the Body’. Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88. doi:10.1080/03085147300000003.

MNA. 2020. ‘Press Conference at Presidential Palace Touches on COVID-19 Issues’. Translated by Zaw Htet Oo. The Global New Light of Myanmar, April 14.

Stover, Eric, and Patrick Vinck. 2008. ‘Cyclone Nargis and the Politics of Relief and Reconstruction Aid in Burma (Myanmar)’. JAMA 300 (6). American Medical Association: 729–31. doi:10.1001/jama.300.6.729.

Seekins, Donald. 2009. ‘State, Society and Natural Disaster: Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar (Burma)’. Asian Journal of Social Science 37 (5). Brill: 717–37. doi:10.1163/156848409X12474536440500.

Warnier, Jean-Pierre. 2009. ‘Technology as Efficacious Action on Objects … and Subjects’. Journal of Material Culture 14 (4): 459–70. doi:10.1177/1359183509345944