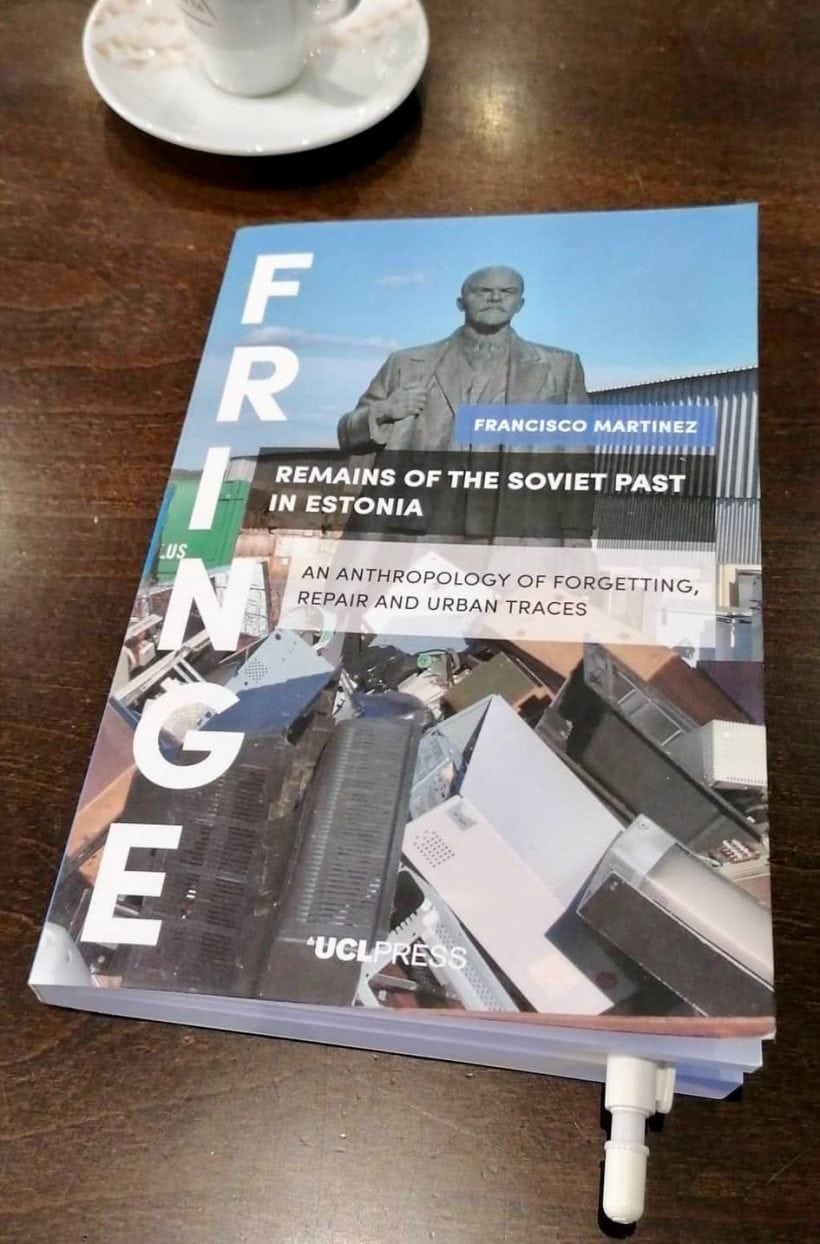

Keiti Kljavin interviews Francisco Martínez on the afterlife of Soviet cultural heritage and his book Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia (Winner of the Early Career Scholars Award 2018 of the European Association of Social Anthropologists).

KK: Francisco, what was the original trigger of your book? How did you become interested in the concepts of waste and repair?

KK: Francisco, what was the original trigger of your book? How did you become interested in the concepts of waste and repair?

FM: I wanted to understand the afterlives that the Soviet legacy was experiencing in Estonia. Then, I started to pay more attention to repair as a coping mechanism, as a sort of vernacular resource for adapting to radical changes. The idea of repair appeared as a way of working through the past, both empirically and analytically, and with interesting material and generational nuances. For example, while talking to repair workers whose skills had been devaluated in postsocialism, I realised that repairing grants a person dignity. Based on this, my book proposes to extend that approach to Soviet legacies, not for whitening them, but as a way of making legacies available to new generations. The recuperation of wasted legacies sets the bases for epistemic repair, making the past available in a different way.

While studying how remains of the past are reworked in the present, I also learnt that Soviet legacies were reduced to waste as part of the official strategy to build up the new state. Neglect had thus a practical use in building up national identity and making the state legible; that’s what I tried to capture with the concepts of “active negligence”, “condemnation of memory” and “wasted legacies”.

KK: Don’t you not think that a great deal of stressing of the continuities with the pre-war Estonian Republic and the illegality of Soviet rule were understandable, given that in 1991 the survival of the re-independent country was uncertain?

Any new political regime inevitably involves a high degree of active forgetting as a consequence of a novel articulation of collective memory. Memory produces neglect by selecting what to care, and the new tends to make the old superfluous and redundant. But the Soviet past remains as a meaning-making reference. We can even say that postsocialism has been a way of reconstructing the recent past even more negatively than it was in order to measure the new present against it.

Then, for a couple of decades, the European Union brought normative and economic stability to Estonia; but we are now learning that such form of political solidity and wellbeing might end anytime, returning again to abrupt changes as the condition of existence of Estonia as a country. The making of Estonian citizenship and identity also remains an incomplete project until the grey passports problem is resolved politically, not biologically. Personally, I am also surprised that Russian is still not recognised as an official language in Estonia, at least in Ida-Virumaa (Eastern region). In 2020, it is a political anomaly.

I’m not interested in assessing if officially arranged forgetting is understandable or not, but to study the side-effects of such institutional strategy and the material and social disinvestments that it entails. Likewise, it is not my intention to judge whether forgetting is wrong or necessary, but rather to put the ethnographic eye on the iterance, traces and affects that forgetting generates. My way of being political is different than the one of a policy-maker.

In postsocialist countries, the past has not been a preparation for the present

KK: How?

I believe that my research is political by what makes visible, not by indicating to politicians what to do. For instance, my work makes visible how forgetting was a desirable goal and positive process for some social actors, but not necessarily for the whole society, especially when a community shows a diverse ethnic composition, as it is the case of the Estonian. Forgetting entails a separation, relegating certain histories, people and spaces to the margins of normality. Does it mean that collective memory is wrong? Of course not! Rather it raises the question of whether people have any past to share as a plural community. And it also shows that, in postsocialist countries, the past has not been a preparation for the present.

KK: How does the Estonian case question the analytical value of postsocialism as a concept?

When combined with other ingredients, postsocialism is still a tasty concept. Try out, for instance, ‘illiberal postsocialism’, ‘architectural postsocialism’, ‘short-minded postsocialism’, ‘standardizing postsocialism’, ‘post-post-socialism’, ‘forensic postsocialism’… we could stay the whole afternoon figuring out interesting combinations.

More seriously, I started my fieldwork relying on Caroline Humphrey’s observation that generational replacement will make postsocialism disappear as a category, but during the research I changed my view and learnt that this concept is rather mutating, acquiring new meanings and explanatory potential, while leaving behind some others, and also travelling to other regions. So, still postsocialism is helpful for understanding contemporary experiences and for engaging with wider debates around the world, but in ways that might be different from those who worked with the concept in the 1990s. Hence, more attention should be paid to how the first post-Soviet generation makes use of concepts such as postsocialism and Eastern Europe.

Overall, the book demonstrates that the socialist legacy is still essential to an understanding of current developments in Estonia. However, my intention was not simply to reclaim the Soviet legacy and its value, but to assess what postsocialism does and how it takes place and time in a multi-scalar picture.

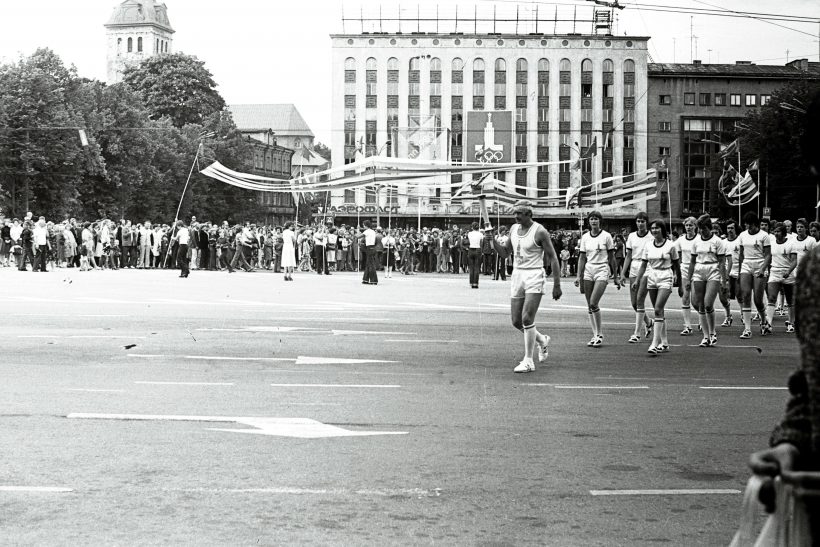

KK: The chapter that studies the afterlife of the Linnahall, the multi-purpose venue designed for the 1980 Moscow Olympics is one of the bests. But in this case, you advocate that the building should be left as “a curated ruin”.

This could be my favourite chapter in the book too. It is the first one I started writing and the last one I finished, because I wanted to make the whole structure more dialogical and to give more voice to the janitors, for example by including a series of photos taken by Peter, instead of simply including their statements as informants.

In Linnahall, one gets an impression of how certain buildings can be instrumental in reconciling the past, present, and future of a city. As a premature ruin, Linnahall is paradigmatic of what I mean by “wasted legacies”, referring to vestiges that cannot be integrated within newly created structures and orders of worth, mostly because of political reasons yet also due to infrastructural issues.

As waste, Linnahall stands in excess. My suggestion to take care of the building as a curated ruin is one among other different proposals for the building; it is inspired by the work of Caitlin DeSilvey and Gabriel Moshenka, a geographer and an archaeologist. This shows the multidisciplinary character of my research, what I called in the book “a fringy anthropology”.

Things are beautiful not because of being made, but because they last in time

KK: Can you explain more, what’s fringy in this type of doing anthropology?

Fringy means to have a proactive initiative in the field, to be open, and loose, and indisciplined, and experimental, and in some instances loose. I suggest decentring ourselves a bit more, in a horizontal, or dialogical way. It is increasingly important to acknowledge the capacity to analyse complex information of our informants, instead of always writing vertically the knowledge of others.

As I see it, the main aim of anthropology is to become aware of the limits and fragility of one’s own world. Traditionally, we have done so by acting as professional strangers, borrowing epistemic positions. But nowadays our ethnographic subjects have become knowledge makers of analytical knowledge, and not simply knowledge holders, as colleagues like Marcus, Collier, Ferguson, Estalella and Sánchez Criado have noted.

Hence, I suggest decentring ourselves a bit more, in a horizontal, or dialogical way. It is increasingly important to acknowledge the capacity to analyse complex information of our informants, instead of always writing vertically the knowledge of others. Indeed, the most interesting anthropological ideas are nowadays appearing outside traditional disciplinary gates and academia. Policing the boundaries of anthropology is, therefore, counter-productive; more a sign of weakness than of strength.

KK: The focus on repair, and how it contests the short-term thinking incentivised by neoliberal capitalism, is interesting. You interview a number of people whose skills depend on repairing rather than producing, which have obviously become less useful in a late-modern society.

The study of repair is important and fruitful because it helps us to understand the current shifts in the relation between technology and power, and also between politics and bodies. It is paradoxical how discourses of ‘newness’ and innovation influence the public discussion of today’s Estonia. While, on the other hand, there is an increasing fascination with old past forms, translated into memory, souvenirs, utopia, nostalgia, stranger things, and what not. It is even more complex, since despite current discourses of sustainability, we see a certain arrogance towards the recent old. Modern ideals make us believe that the urgent is to create more new things, while the important is actually to make things durable. Things are beautiful not because of being made, but because they last in time.

KK: This tension generated by how the vanquishing of old traces follows a different time than the political is also reflected in two other concepts of your book “aesthetics of amalgamation” and “architectural taxidermy”. Could you expand on this?

KK: This tension generated by how the vanquishing of old traces follows a different time than the political is also reflected in two other concepts of your book “aesthetics of amalgamation” and “architectural taxidermy”. Could you expand on this?

In my research, I am interested in overcoming the preservation / demolition dichotomy, and explored the possibility of having a category in-between, such as “architectural taxidermy”, which is a form of chimaera, a hybrid thing composed of parts from different architectural bodies. In the book, this concept applies to the way buildings come to terms with the new values, technology and social organisation. However, this notion of “coming to term” would be too rational, since it is a rather sinister form of domestication.

These concepts are an invitation to think temporal regimes in terms of mutation and side-effects; instead of a straight linear evolution. Less than ever, social and material changes won’t be comprehended if merely applying a diachronic study, as many historians do. We need multiple ways of temporal representation, to combine heterochrony and dyssynchrony in academic research, as done, for instance, in contemporary art and contemporary archaeology.

An example of this is the former Postimaja (in Tallinn), designed by Raine Karp, and nowadays transformed into a shopping mall. The taxidermic renovation was based on the belief that past traces were not needed, only a recognizable face of the corpse for domesticated touristification. What was originally proposed as a form of historic preservation, in practical terms it meant killing the building. Unfortunately, post-war architecture is still not thoroughly protected in Estonia. Because of being made during the Soviet time, they have been too often dismantled by pretending that they were being renovated, as if it were architectural taxidermy.

Regarding the other concept, I approached Tallinn’s cityscape as an archive, paying attention to composing and decomposing materialities. Unfortunately, there is an intense uniformisation going on in town, and also efforts to cleanse the city’s historical complexity, as in the case of the Maarjamäe Memorial

KK: One of the most affective parts of the book is about your repeated visits to Jaama Turg (Railway Station Market) and your conversations with the people there. What do you think the city has lost with its removal?

I am also fond of this chapter because it combines politics, material culture and methodological experiments in an intertwined way. Obviously, there has been improvement in the material conditions of the market, after the input of the new real-estate company. What I suggested in the chapter, however, was to go beyond the good and bad dichotomies, in order to see what has been lost in the process of change, and what is the contribution of the new place to the city at large. Despite being materially and economically precarious, the former market enabled diversity, was a gateway to the city centre for people living in the suburbs, and a space of camaraderie for those who were on the losing end of postsocialist transformations and globalisation, remaining more isolated and invisible in the suburbs these days.

Inclusiveness and accessibility are important in Tallinn, a city in which nearly half of the population is Russian speaking and the other half use Estonian, and with increasing economic inequality. With the new market, Tallinn has gained a new space for retailing services in the form of a shopping mall for hipsters, yet it has lost a place that was distinct. It could have been otherwise, if the municipality would have invested some resources in upgrading the market, and applied regulations to limit ongoing gentrification.

KK: Your chapter about Narva reflects the plurality of experiences and identities found there by including the views of local people, who are variously positive, negative and completely indifferent towards the subjects of Estonia, Russia and the existence of a border separating them from Ivangorod across the river.

In the book launch at the Püant bookshop, (human geographer) Tauri Tuvikene said that he read Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia as an ethnography of Tallinn, and that the chapters about Narva and Tartu were placed as mirrors of the capital. To be honest, I did not think my research in these terms, but it made sense what Tauri observed.

I wanted to show that Narva is ordinary in its own terms; catching a bit of the way of getting something done that is there, in contrast to the rest of Estonia. This is why the chapter has a kind of dialogical structure, as if the reader was taking a walk in the city and chatting with the people encountered on the way. Local narratives show a wide range of levels of adhesion and deviation; for instance, ethnic Estonians might be presented as neighbours, rather than as belonging to one and the same family. But this does not mean that the rest are anti-Estonian, or non-Estonian; rather that they extend the political, cultural and religious meaning of what is to be Estonian, redrawing the contours of the nation-building project.

We tend to think of politics as a process of gaining consciousness about our surroundings, but quite often to be political is not a choice, one might become politicised also from external factors or actors, by being born in the wrong place, by their gender or sexual orientation, or by having a particular ethnicity. In many cases, people do not cross the line of politics, but it is the very line which crossed them, presenting rare features that could be well experienced as normal. This is the case of Narva, a city that is now on the border of the EU and NATO, and in which people who were calmly living in what they considered their country still have no citizenship or jobs. They became separated people, in the sense of living in-between, being neither fully Russians nor Estonians; but somehow from a divorced family.

Taking Narva as a centre out there will help this society become more inclusive and considerate of differences. Estonia is a small country, but not everybody here partakes of official narratives about the past and future. Nor it should be like that.

An excellent piece and view and historical perspectives of a post-communist society.The interesting “moulding” of the narrative regarding the complex nature and acceptance of the remnants of the former ruling force of only 30 years ago, which is now awkwardly playing out at the present time in society. This region with its incredibly turbulent and tragic past is one of the most susceptible to the potential writing of fairy tales regarding its history, people are unwilling to look into their own past in case they find something shameful and unsavory (and unfortunately in very many cases, they do).