Areej Sabbagh-Khoury. 2024. Colonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian Nakba. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

In Colonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian Nakba, Areej Sabbagh-Khoury sets out to understand how socialist groups within the Zionist movement navigated their role in the colonisation of Palestine. Using the archives of three kibbutzim[1] associated with the pro-labour and bi-nationalist Hashomer Hatzair movement, along with what individual memories, collected through interviews, letters, and the colonial archive, still exist from surrounding Palestinian villages, Sabbagh-Khoury takes her readers back to the decades leading up to 1948. While this year marks the founding of the modern state of Israel and is commemorated within Israel as the Israeli War of Independence, for Palestinians, 1948 constitutes the Nakba: the catastrophe.

In Palestinian collective memory, no war occurred. Rather, Palestinian villages were massacred by the Zionist Haganah Militia, hundreds of thousands were displaced, and dreams of Palestinian statehood were effectively demolished.

While this year marks the founding of the modern state of Israel and is commemorated within Israel as the Israeli War of Independence, for Palestinians, 1948 constitutes the Nakba: the catastrophe.

Sabbagh-Khoury does not look to account for the logical and moral justifications of self-proclaimed leftist Kibbutzniks’ participation in the colonial violence and dispossession of Palestinians. Instead, her work shows how the material conditions of settler colonialism shaped and were shaped through ideology. A Palestinian citizen of Israel and Professor of Sociology with appointments at both the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the University of California, Berkeley, Sabbagh-Khoury elegantly demonstrates a commitment to both academic rigour, as well as to rendering legible to readers the fraught and heavily politicised relationship between Palestine and Israel. By showing the complexities of these relationships, Sabbagh-Khoury emphasises that settler-colonialism be understood not as a series of key events and points of rupture, but rather through explaining “[…] material practices […] reversing the intention of the kibbutzim’s historiography and memory production and subverting the gaze of colonial […] documentation” (39).

The book examines the cases of three Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim – Mishmar ha-Emek, Hazorea, and Ein Hashofet – and their relationships with the nearby villages of Abu Shusha, al-Ghubayyat, Qira, Abu Zureiq, Jo’ara, and al-Kafrayn. Socialism, Sabbagh-Khoury suggests, became an influential factor in both distinct phenomenological encounters between Hashomer Hatzair Zionists and Palestinians, and in the methods and strategies employed by the Zionist movement. From the first chapter, she demonstrates the challenge of describing the locations of the communities, given that even geographical names have variations in meaning and points of reference between Arabic, Hebrew, and English. With this divergence in mind, she points out the difficulties of finding a vocabulary fit to describe historical processes and events that are neither extricable from Palestinian and Israeli memory nor politically and emotionally compatible. Her deep descriptions of such contested terms as settler colonialism invite the reader to see different terminologies and interpretations as overlapping spaces on the geography of memory, rather than as sites of contention. This effort to both expose and transcend contentions between Israeli and Palestinian memories and worldviews makes reading Sabbagh-Khoury’s work both profoundly compelling and profoundly unsettling.

The book starts with the founding of Mishmar ha-Emek in 1926. It then turns to the settlement and growth of the three kibbutzim, their eventual participation in the suppression of the 1936 Great Arab Revolt, and the expulsion of many of their Palestinian neighbours in 1948. It follows the land accumulation of settlers, which occurs at times with little fanfare, at others through exploitation of the complex and sometimes ambivalent land tenures laws of the Ottoman and British empires, and at still others through direct acts of violence. Sabbagh-Khoury notes that Zionists and Palestinians engaged in trade as neighbours, with Palestinians initially making hospitable overtures towards newly arrived Zionists. Yet it was rare for Zionists to approach their Palestinian neighbours as peers. Rather, Zionist engagement was driven by motivations ranging from the mixed socialist-paternalist belief that they could teach Arabs the skills needed to fit into Zionist national ambitions, to a more sinister effort to understand and surveil communities for the benefit of militias. In response, Palestinians undertook uneven forms of resistance, including practices that were driven by both social class and their unique experiences with a specific neighbouring kibbutz. These efforts ranged from sporadic violence between individual Palestinians and Zionists, all the way up to the Great Arab Revolt of 1936, in which Palestinians rose up against both Zionist settlers and the British Mandatory government to protest the massive shifts in land tenure. Through settlement, conflicts over land, and the eventual expulsion of Palestinians, Sabbagh-Khoury recounts moments of conscious decision to escalate violence and dispossession, as well as the divergent aims pertaining to Zionist or Palestinian projects respectively.

The interviews and archival material demonstrate that both Zionist settlers and Palestinian villagers understood the gravity of their situations, but without knowing how deeply the ruptures of 1948 would be felt. In one snapshot, a settler of Ein Hashofet recalls how she and other children were gifted looted jewelry from the neighboring village of Qira, after its inhabitants had fled. The kibbutz school teacher, in an act of both religious and political righteousness, instructed the children to gather the jewelry and bury it until it could be returned safely to its proper owners. The people of Qira, however, are never able to return, and the location of the buried jewelry is eventually forgotten. The realities of war and dispossession are keenly felt against the innocence of children who do the right thing by giving up their looted treasure, intending to return a box full of trinkets to a people who have just been permanently displaced from their lands and livelihoods. These stories are valuable fissures in a landscape where memory is shaped by the interests of the powerful.

Colonial violence in the present follows a path that has been laid through past decisions and may not have otherwise existed. Memory can justify this violence, but it can also point to the prior existence of other possible futures.

The last chapters of Colonizing Palestine are dedicated to settler colonial memory, or the way in which colonialism reshapes the past, creating a neat narrative of inevitability and legitimacy. In one 1994 interview retrieved from the Mishmar ha-Emek archive, a settler named Elisha Lin enumerates the villages that once surrounded his kibbutz, translating their Arabic names, and describing fragments of their history. He remembers the mundane details of life, such as one village’s abundance of cultivated fruit, as well as incidences of violence between kibbutz residents and villagers, and eventually the ways in which villages were depopulated or destroyed in 1948. Following the extract from the interview, the text continues, “This reads as though Lin were a Palestinian describing the uprooted villages in the area before the Nakba with precision and great knowledge of the surroundings. The complete map of the region is preserved in his memory and at times he slips into speaking of the villages in the present tense. The map is not empty” (199). Despite Lin’s position as a settler, his memory is proof of Palestinian presence. Yet even though the record of Palestinian existence is evident in both individual memories and the kibbutzim archives, both individuals and institutions take pains to construct narratives and rework national memories in ways that emphasise the legitimacy and good intentions of Jewish settlers, while describing Arabs as backwards, disorganised, and lacking deep connection to the land. By exposing these two sides of memory, in challenging the inevitability of political history, Sabbagh-Khoury herself confronts the inevitable intervention of the historian into politics. Colonial violence in the present follows a path that has been laid through past decisions and may not have otherwise existed. Memory can justify this violence, but it can also point to the prior existence of other possible futures.

This is, perhaps, the reason why Colonizing Palestine ends up providing more insight into settler colonialism than it does to socialism. While socialist ideas are present in the threads that the book follows, Sabbagh-Khoury herself admits that her main theoretical contribution is to advance an understanding of settler colonialism, which she sees not as an event, but rather as a protracted process characterised by the agency and the negotiation of uneven power relations between Zionists and Palestinians. Socialism, the belief in the brotherhood of nations or the ownership of land by those who work it, she argues, was more instrumental in justifying the creation of a modern Jewish state than it was in providing ground for a bi-national political project.

The final pages of the book thus turn to the 21st century, and activists’ current efforts to fight the erasure of memories and records of villages that were destroyed in 1948. In closing, Sabbagh-Khoury’s writes that “instead of viewing settler colonial beginnings as leading inevitably to the 1948 Nakba, the Israeli State […] and the hyper authoritarian turn of Israeli politics in the 2010s,” instead her work “has insisted on examining the political ‘raw materials’ that would prefigure later processes” (270). By understanding settler colonialism as process, one can begin to resist the idea that the contemporary violence and dispossession in Israel/Palestine are destined to continue.

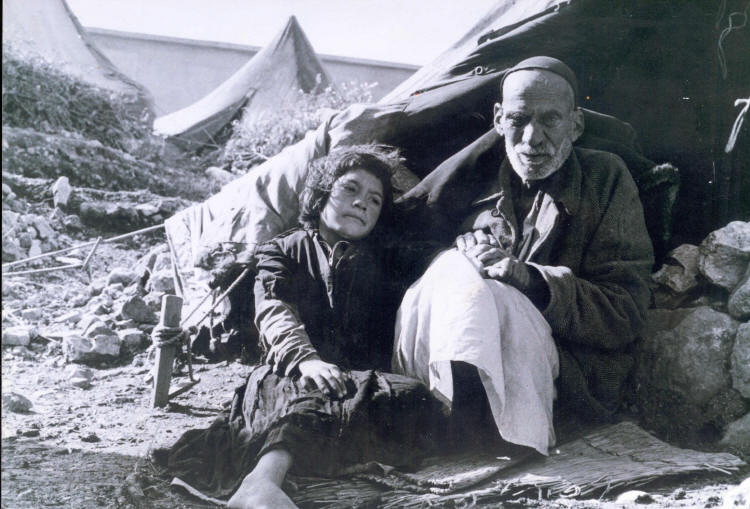

Featured Image: Oldman Girl Nakba, Hanini. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Notes

[1] Kibbutzim (singular: kibbutz) refer to communal, often agricultural settlements formed by Zionist immigrants and colonists in the early 20th century.