A couple of months ago, I was trawling Twitter looking for inspiration when I came across a notice that Libraria – a collective of researchers based in the social sciences – was hiring a Community Convenor. It grabbed my attention because it didn’t sound like your average scholarly communications job. Even more startling was the fact that the position did not require scholarly publishing experience (though it was recommended). Instead, the focus was on community organizing skills. It was a job designed to help small, scholar-led, open access (OA) publications in anthropology and adjacent disciplines build a mutual aid network of sorts. Wow, I thought. What a great idea!

OA wins the day – or does it?

I’m a relative newcomer to OA, having built a career in the non-profit university press world. But I had always kept my eye on new developments (like Plan S in Europe and, more recently, Libraria’s pilot project with Berghahn Open Anthro, as well as scrappy OA publishers like Punctum Books), and had started to realize that the writing was on the wall: it was only a matter of time before OA would become the dominant model for scholarly publishing, starting with journals. There has, of course, been a simultaneous push for academic publishers to publish more trade titles – i.e., those that are commissioned, shaped, and marketed to appeal to a much broader book-reading public. I know this market well, as I helped transform many an academic project into more public-facing books, but I also know how many copies you need to sell to cover the extra costs involved in production, marketing, and distribution; only a small proportion of scholarly research fits the bill. University presses know this too, which is why many are balancing the push to trade publishing with experiments in open access. The MIT Press Direct to Open (D2O) project is a good example of efforts to find synergy between these impulses.

There has also been a growing gap between openness and accessibility and the business models that have emerged to support this form of publishing.

As OA has gained more and more traction, there has also been a growing gap between the values of both openness and accessibility and the business models that have emerged to support this form of publishing. As far as I can tell (and as this collective of researchers has elegantly articulated and rearticulated), the big gains in OA publishing in recent years have relied on either article processing charges (APCs) or “read and publish” deals, neither of which appear to challenge the underlying balance of power in scholarly publishing. As the old saying goes, the more things were changing, the more the inequalities in publishing remained the same: large commercial publishers that owned prestige journals were still doing just fine, thank you very much; university presses were looking for some kind of footing in a quickly changing environment; and small, scholar-led, open-access publications were further relegated to the margins of the scholarly publishing world.

Finding common cause

Enter Libraria’s Cooperate for Open project, an initiative designed to support these intriguingly marginal publications by fostering a sense of collegiality and community, rather than making them over in the familiar image of competition and prestige. In 2021, Libraria hired Kate Herman, now the interim managing editor of Cultural Anthropology, to survey a group of Diamond OA publications in anthropology and adjacent fields. What she found was that these scholar-led journals take on the work of publishing not primarily to boost their editors’ careers but because the publications are, as the collective mentioned above insists, “labors of love.” They are committed to pushing discussions about the politics of infrastructure and the boundaries of what counts as legitimate scholarship within their scholarly communities, including in some cases bringing research to broader audiences. And they are committed to doing this on an open-access basis, scraping together funds from whomever they can – academic institutions and departments, libraries, or (less often) governments and other funding bodies – to make it happen. Why? Because the scholar-publishers behind these projects believe that what they do is a worthwhile contribution to their scholarly communities and to the public at large. And what do they get in return? They usually don’t receive much credit within the academic star system for working on these publications. And the work they publish doesn’t always get the readership it deserves, because they don’t have the time or resources to secure that level of attention. What they do get is a sense of scholarly integrity – along with a healthy dose of burnout that comes from the ongoing technical, financial, time, and labor pressures they face.

They are committed to pushing discussions about the politics of infrastructure and the boundaries of what counts as legitimate scholarship.

What was clear to me in the feasibility study that came out of this research is that these journals aren’t asking for help to scale up in size or to tap into the prestige economy that characterizes so much of scholarly publishing. They know all too well that growing too fast or too large has its own limitations: more work adhering to stringent reporting procedures, more standardized content, less experimentation, and less autonomy. What these publications really want is to be able to continue doing what they do well: focusing on creative and sometimes niche content, without having to worry excessively about the financial, technical, or bureaucratic issues often involved in running a publication. What they want, in Herman’s analysis, is a mutual aid network that allows them to share knowledge and costs, but also helps forge a common voice to articulate the quality and rigor of the work they do: amplifying their work without compromising their independence.

What these publications really want is to be able to continue doing what they do well.

Interestingly, there appears to be growing momentum for supporting this scholar-led Diamond OA publishing sector. The Cooperate for Open (C4O) report coincided with the publication of another report and subsequent action plan by cOAlition S in Europe (the architects of the Plan S mandate). The tone of these two reports feels very different, though. Where cOAlition S refers to the need for efficiency, standards, and capacity-building, the C4O report invokes a community of practice, room to experiment, and preserving autonomy. While cOAlition S is working to scale up and professionalize Diamond OA publishing, Libraria and the as yet diffuse group of scholar-led publications that they have assembled are most interested in “exploring mutuality”. Because, according to Herman, while these publications all faced similar challenges and occupied similar spaces in their scholarly worlds, there was little in the way of formal connections between them to enable cooperation.

Making common cause

This brings us full circle to that Community Convenor job posting. The next phase of the C4O initiative begins right now. In the coming months, I (yep, I got the job!) will be working with these scholar-led publications to see if we can find ways to build some connections that will outlive my involvement in the project. What kind of connections? I’m not sure yet, but there are plenty of ideas to build on coming out of the feasibility study: from building discussion platforms that allow for greater peer-to-peer sharing, to expert-led information sessions dealing with everything from DOIs to managing the risks of open licenses. There might even be an appetite for a collective funding model down the line, which could match bundles of publications with mission-aligned funders so they gain some of the benefits of a bigger collective without trading away their autonomy or the bases of support they have already cultivated.

Re-evaluating scholarship based not on prestige or privilege, but on the quality and generativity of the work itself, is crucial.

I would say that the sky’s the limit, but given the timeline and the resources at hand, that’s not true. What is true is that supporting and encouraging bibliodiversity is worth our efforts. It’s true that a challenge to the competitive and extractive business model of publishing in favor of collegiality and justice is desirable for many. And it’s also true that re-evaluating scholarship based not on prestige or privilege, but on the quality and generativity of the work itself, is crucial. This is what the scholar-led OA publishing model stands for. And its proponents know that if these publications are going to succeed in the future, they will need to make common cause.

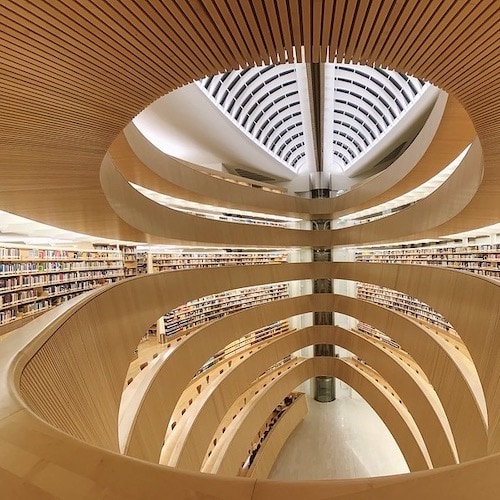

Featured image by Ank Kumar, courtesy of Flickr.com.