As I write this, in the uncertain and tumultuous times of early June 2020, there is a storm brewing in the world of British tea drinkers.

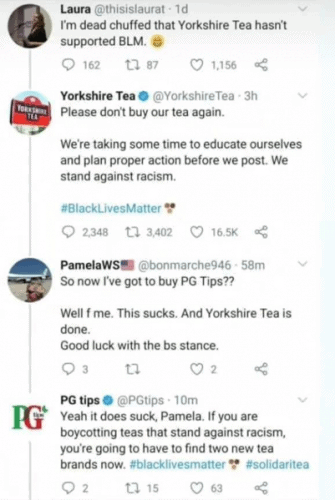

On June 6th, a Twitter user posted “I’m dead chuffed that Y orkshire Tea hasn’t supported BLM”. The next day, Yorkshire Tea’s account replied with the following:

orkshire Tea hasn’t supported BLM”. The next day, Yorkshire Tea’s account replied with the following:

“Please don’t buy our tea again. We’re taking some time to educate ourselves and plan proper action before we post. We stand against racism. #BlackLivesMatter”. A flurry of social media posting began to unfold in response, with user @PamelaWA lamenting, “So now I’ve got to buy PGTips?? Well f* me. This sucks. And Yorkshire Tea is done. Good luck with the bs stance.” PGTips, for their part, shot back: “Yeah it does suck, Pamela. If you are boycotting teas that stand against racism, you’re going to have to find two new tea brands now. blacklivesmatter #solidaritea”

‘Please don’t buy our tea again.’ Other major UK tea brands such as Teapigs, Tetley, and Twinings all swiftly joined the online #solidaritea conversation.

Other major UK tea brands such as Teapigs, Tetley, and Twinings all swiftly joined the online #solidaritea conversation. The invocation of #solidaritea and public proclamations of good corporate citizenship on behalf of these tea companies, however, stand on shaky grounds—grounds of colonial and imperial exploitation, labour abuses (both gendered and racialised), and long-term environmental impact.

These themes have been deftly explored by Sarah Besky throughout her corpus of work on tea in India, and have crystallised in her most recent book, Tasting Qualities: The Past and Future of Tea. Watching the rise of #solidaritea unfold online in the days after I finished reading the book, I found myself particularly grateful for Besky’s historically-grounded approach. In placing sensory ethnographyand political economy in dialogue with temporal shifts, archival research, and historical methodologies, Besky shows the ever-changing uses and definitions of quality within the tea industry. In this way, we can begin to understand the moral claims at play in the #solidaritea discussions as part of a larger project of constructing and selling quality.

Besky opens the book by asking, “What makes a good cup of tea?” (p.1). As we come to see, quality is constructed both materially and chemically and in relation with the body and environment, but also in relation to valuation processes, state intervention, and consumer-end marketing discourses. Reading Besky in the context of #solidaritea, then, gives us a concrete consumer-end example of how moral positioning intersects with and helps constitute ideas of quality, while also illuminating the possible tensions and contradictions between two primary forms of quality: ‘the quality of things produced for the market and the quality of life for the people who produce and consume those things’ (p. 130).

Reading Besky in the context of #solidaritea, then, gives us a concrete consumer-end example of how moral positioning intersects with and helps constitute ideas of quality, while also illuminating the possible tensions and contradictions between two primary forms of quality: ‘the quality of things produced for the market and the quality of life for the people who produce and consume those things.

Tasting Qualities links these two strands of quality through the material and chemical composition of the tea itself. This has been a relatively under-explored and under-theorised area of sensory ethnography: The book’s focus on‘cheap tea’—which is grown and blended for standardised tasting experience—over high-end, specialty, single-estate tea—which is prized for its unique and identifiable tastes—provides the ideal platform for examining how social tastes and norms mix with physical properties and chemical compounds to create holistic ideas of quality. If every bag of ‘cheap tea’ needs to taste the same, provide the same sensory experience, and be enjoyable, then a major technical and social operation must ensure this is the case. As the later chapters of the book show, the quality standards needed to maintain consistent flavour in blends can partly explain the persistence of the monoculture plantation system in India, despite reform efforts from both the state and external development NGOs. Even when plantations are broken up, smallholders in areas surrounding plantations are still encouraged to grow tea. And while production methods are, in some locations, evolving along new and more collaborative models, the primacy of monoculture has yet to be substantively changed. In this way the seemingly abstract notion of ‘quality’ begins to map itself onto the landscape and environment, imperial histories and contemporary mainstream economic logic, the bodies and lives of workers (agricultural and otherwise), and—through blends and physical consumption—the end consumer.

The most evocative ethnographic passages in the book come early on as Besky places us with professional tea tasters and brokers who begin the formalised process of qualification—setting prices, selling at auctions, and diverting teas into lots for blending. Later, we revisit the auction house for the launch of digital auctions, and the sense of loss felt by brokers is plain. The shift away from the outcry auction format—one which was intensely social and requiring the in-person presence of representatives from tea-trading firms—as well as the shift in valuation engendered by the digital medium (which requires an a priori assessment of a tea’s monetary value, instead of a negotiation of it during the act of outcry auction), ultimately placed tea more squarely within contemporary financial capitalism. I was struck by some of the oft-overlooked phantoms of commodity chain studies: the middlemen and brokers, who though adjusting over time to the new format, lost something of fulfilment, and of personal quality of life and connection to their work. As Besky writes, the shift to ‘…digital trading was a perceived violation of an aesthetic and ethical connection between a style of trading, a style of production, and a style of consumption. Unlike commodities traders in Chicago or London, who have little material connection to the products they buy and sell, tea brokers knew tea—and tea plantations—on intimate terms’ (p. 168).

Given the British interest in a good cuppa was created by the colonial project and through exploited bodies, labour, and environments through British colonial history until present day, questions of corporate responsibility and response to solidarity and justice movements like Black Lives Matter must necessarily be looked at within an expansive network of history and practice.

This last reflection brings us back to #solidaritea. Given the British interest in a good cuppa was created by the colonial project and through exploited bodies, labour, and environments through British colonial history until present day, questions of corporate responsibility and response to solidarity and justice movements like Black Lives Matter must necessarily be looked at within an expansive network of history and practice. For those Twitter commenters who were aghast at tea companies’ support of Black Lives Matter, the overall perception of the quality of the brands decreased; the inverse was true for those who pledged to stand in #solidaritea with Yorkshire Tea and the others. The tea and its material quality may remain the same in this instance, but quality is also contingent upon both its social and historical situatedness. While the book is subtitled ‘the past and future of tea’, the overall project it tackles is larger than only tea, pointing the way to the future of wider quality definitions and negotiations. Quality, as both Besky and #solidaritea show us, remains not only in motion but also—despite the prevalence of experts and technoscientific processes throughout the chain of production, despite standardisation and attempts at sameness—open to debate, interpretation, and change.

Read Ishita Dey’s review here.

Read Tanya Matthan’s review here.

Featured image by Free-Photos (courtesy of Pixabay)