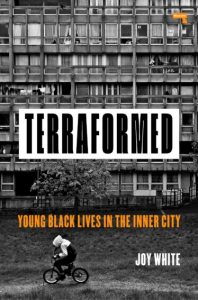

Terraformed by Joy White aims at making sense and contextualising the vulnerability and inequality experienced by the Afrodiasporic population of the UK. The author describes her effort as ‘connecting the dots’ (pag. 2) between the struggles of the British Black working class community and the wider institutional and historical context. She concentrates on a square mile, the area of Forest Gate, in East London, a place she knows very well as she lived there for many years. White offers a new theoretical framework to the study and understanding of the urban environment, which she calls hyper-local demarcation. This framework allows to look at how power dynamics and racialised narratives work locally, at the level of the street, and impact on Black lives. The four dimensions of the framework—legislation, communities, sonic landscape and town planning—are interconnected in shaping the lives of young Black people living in the area . Each chapter offers an analysis of how this framework operates in the everyday.

White opens the first chapter recounting her experience of racism during her first job in a Civil Service department in Newham in the late 1970s. This incipit positions the author in the study and highlights her motives for the writing of this book. White gives us a detailed geographical and historical description of the area identifying how it became a poor, multicultural neighbourhood clearly connected to the British colonial past and the fate of the Royal Docks. Describing the political context of Newham, White concentrates her analysis on the effects of decades of austerity which have augmented the challenges experienced by Newham’s inhabitants. Austerity drove policy changes that established neoliberal values, such as the pursuit of profit, behind many state institutions. Many public services were privatised, benefits for households were capped, and community resources depleted. As a result, many disadvantaged people found themselves juggling with stagnating income, precarious working conditions, and rising living costs while the quality of public services and social housing plummeted. These effects were especially felt by the Black population: in 2013, youth unemployment rose to 45% for Black youth, compared to 18% for white youth (p. 28). White denounces how austerity fuelled a rise in poverty and ill-health, both mental and physical, while removing safety nets for people who are struggling (p.97). All of this happened with little resistance from the public:

White opens the first chapter recounting her experience of racism during her first job in a Civil Service department in Newham in the late 1970s. This incipit positions the author in the study and highlights her motives for the writing of this book. White gives us a detailed geographical and historical description of the area identifying how it became a poor, multicultural neighbourhood clearly connected to the British colonial past and the fate of the Royal Docks. Describing the political context of Newham, White concentrates her analysis on the effects of decades of austerity which have augmented the challenges experienced by Newham’s inhabitants. Austerity drove policy changes that established neoliberal values, such as the pursuit of profit, behind many state institutions. Many public services were privatised, benefits for households were capped, and community resources depleted. As a result, many disadvantaged people found themselves juggling with stagnating income, precarious working conditions, and rising living costs while the quality of public services and social housing plummeted. These effects were especially felt by the Black population: in 2013, youth unemployment rose to 45% for Black youth, compared to 18% for white youth (p. 28). White denounces how austerity fuelled a rise in poverty and ill-health, both mental and physical, while removing safety nets for people who are struggling (p.97). All of this happened with little resistance from the public:

Austerity has hushed the voices of the poor, the disadvantaged and the marginalised. As civic participation often declines in more unequal societies, it allows toxic policies to be implemented unchallenged (p. 35).

White accuses capitalism’s predatory nature for destroying our capacity to care for each other while denouncing the little accountability of privatised services which, driven by profit, are too big to fail despite their inability to provide quality services. She brings to our attention the cases of Carillon, Serco and G4S. Each of these companies employs thousands of people, many of them living in the area, offering various kinds of services from security and prison management, to health care and soft facilities management (including catering and cleaning at local hospitals).

The central chapters of the book are an ethnographic account of how people from different backgrounds live in Forest Gate side by side yet separated. Young Black men, often poor and jobless, spend their free time in public spaces socialising and making music. Grime music is a musical genre that emerged from Newham and its connection to place is evident in the lyrics, which reference local place-names, and in the music videos, which show Forest Gate corners and its youth. White argues that music and performance allow young Black men to creatively express opinions that are otherwise silenced in other public arenas. Nevertheless, town-planners and their regeneration projects are maginalizing these young men by labelling them as troublesome, disrupting their social interactions through policing and effectively pushing them out of the public space. In the area pockets of whiteness are now emerging: leisure spaces and local businesses cater to the new white inhabitants while Black youth are excluded, either because they cannot afford to consume in such places or because they are made to feel at best out of place, and at worst clearly unwelcom

ed.

The symbolic, structural and slow violence Black youth experience since childhood transforms into physical violence in the streets for teenagers. White juxtaposes the contemporary hostile environment and aggressive policing tactics with the killings of three young Black men in the streets of Newham:

‘Violence to Black lives occurs against a backdrop of five decades of a hostile environment that has erased and ignored the contribution that Black citizens have made. Instead, Black communities have been positioned as a drain on British society and a danger to British norms and British values’ (pp. 91-92).

The author highlights how Black youth experience many kinds of violence and microaggression, living in a ‘perpetual state of anxiety’ (p. 94) fearing prison or deportation.

“Violence is both physical and verbal, gradually permeating everyday experiences until it becomes a sickness, a form of social and emotional suffering. When combined with processes and techniques that make poverty and racism not just possible, but acceptable, maybe we do arrive at a point where for some, life—even their own—has little value” (p. 97).

White shares with us her personal experience of youth violence as she recounts how her nephew was stabbed in the street aged 19. Her evocative and emotional memoir chapter delivers her message with incredible strength. The brutality of structural violence is never at rest for Black people: ‘Seconds after Nico’s life support had been switched off the police walked into the room with a body bag — because in their eye he was [criminal] evidence’ of his own murder, his family treated like a nuisance to the investigation (p. 104).

Terraformed is a short book, but its length does not detract from its strength. White’s contribution to existing literature on legacies of colonialism, racial discrimination and their urban demarcations develops around a new framework of hyper-local demarcation which brings together the dimensions of legislation, community, sonic landscape and town planning. Through this framework, the author delivers a clear analysis of the socio-historical and economic conditions of Newham and the effects of national policies at the micro level of the street. At the same time, this framework allows for a vivid and evocative portrait of the neighbourhood, giving the reader a sense of what it feels like to be a young Black man in Newham today. Written in accessible language and sold at an accessible price, Terraformed should reach a wide audience interested in better understanding how we arrived to the point of needing a Black Lives Matter movement.

Featured Image by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash