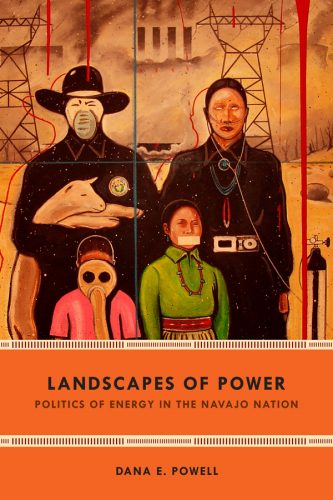

The cover of Dana Powell’s book, Landscapes of Power, taken from a painting by Diné teacher and muralist James B. Joe titled Bleeding Sky, is our first glimpse into the embodied impacts of settler colonial energy infrastructure “made visible in disfigured bodies and ruined landscapes”(Powell 2018:190).

The image of a Diné family from the Navajo nation, wearing masks and requiring oxygen cylinders to breathe set against a backdrop of crisscrossing electrical wires, emphasizes the interconnections of settler colonial violence on indigenous lands and bodies. The image simultaneously implies that indigenous resistance lives on in this refusal to be seen through a colonial gaze. This refusal time and again appears in Landscapes of Power which outlines the complexity of indigenous sovereignty and its historical entanglements with energy politics, amongst the indigenous communities inhabiting the Navajo Nation who identify as Diné.

Powell traces the breakdown of a proposed coal plant called Desert Rock in the Diné community home of T’iis Tsoh Sikaad (Place of Large Spreading Cottonwood trees), renamed Burnham, New Mexico by the US settler colonial project. The failure of Desert Rock raised questions about the Navajo nation’s home being used for energy mining which produced electricity for localities outside the nation while indigenous community members struggled to acquire running water and electricity. Landscapes of Power emphasizes that the battle over Desert Rock which ensued between Dine community members, Navajo nation council members and Sithe Global Power (the corporation behind Desert Rock), revealed that the settler colonial project did not have clear cut political actors. Instead it appeared that indigenous community members held diverse political stands for and against economic ‘development’ through energy projects in the Navajo Nation.

Powell traces the breakdown of a proposed coal plant called Desert Rock in the Diné community home of T’iis Tsoh Sikaad (Place of Large Spreading Cottonwood trees), renamed Burnham, New Mexico by the US settler colonial project. The failure of Desert Rock raised questions about the Navajo nation’s home being used for energy mining which produced electricity for localities outside the nation while indigenous community members struggled to acquire running water and electricity. Landscapes of Power emphasizes that the battle over Desert Rock which ensued between Dine community members, Navajo nation council members and Sithe Global Power (the corporation behind Desert Rock), revealed that the settler colonial project did not have clear cut political actors. Instead it appeared that indigenous community members held diverse political stands for and against economic ‘development’ through energy projects in the Navajo Nation.

What are the acts of resistance demonstrating that indigenous sovereignty does not exist “simply inside nor outside the American political system but rather exists on these very boundaries, exposing both the practices and contingencies of American colonial rule”(Bruyneel 2007:xvii, as cited in Powell 2018:11)? This is a question that Landscapes of Power seeks to answer by emphasizing interconnected yet often divergent voices that come up in the Navajo nation’s challenge and subsequent defeat of the Desert Rock project and the corporations behind it. The aftermath of Desert Rock emerges as a point of convergence and continuing discussion of indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. In these discussions, Diné communities emphasize the historical continuities in the settler colonial logic of dislocating indigenous communities by unmaking the physical and sub-surface constitution of their homelands and rendering them inhabitable. Drawing from my research interests in understanding the embodied landscapes that are intertwined in indigeneity discourses in India, I focus on Powell’s vivid contextualization of Diné placemaking within energy politics and its implications for a just energy future.

Powell weaves an intricate picture of the lived experiences and fears of Diné communities who live in proximity to the proposed Desert Rock site. Community members fear that water sources and in turn their bodies will be contaminated from coal runoffs : this sentiment derives from exploitative histories of uranium mining in the Navajo nation.

This ‘uranium boom’ caused high cancer rates and deaths in the 1980s and was termed “environmental racism and a genocidal act of colonialism” (Shirley 2006, as cited in Powell 2018:51). Diné oral histories and creation stories talk about living in harmony with sub-surface agents such as uranium and coal by preventing human interference with these elements, which when disturbed as Desert Rock envisaged would adversely impact the lives of communities living closest to the site. Community members protested their physical and compositional dislocation from their homes through the narration of creation stories that emphasized their historical connection to their homelands known as Dinetah, that was attempted to be altered by the Desert Rock Project. By recounting memories of Dinetah, and its slow unmaking through coal and energy projects, members emphasized the continuities in the settler history of energy politics while also emphasizing that the fight against Desert Rock was a reclamation of Dinetah.

Powell weaves an intricate picture of the lived experiences and fears of Diné communities who live in proximity to the proposed Desert Rock site.

Sithe Global, the company behind Desert Rock, sought to present the proposed coal based power plant as a global movement towards sustainable energy and used the term “relocation” instead of displacement for the indigenous communities who had homes close to the proposed site. These disguised moves were challenged by activist organizations such as Diné Citizens Against Ruining our Environment (Diné CARE) that mobilized ethical-cosmological thinking . Landscapes of Power thus brings into focus the transnational language of the settler logic of elimination (Wolfe 2006, as cited in Powell 2-18:9) while contextualizing it within conversations about global capitalism and climate change.

Similar discourses are seen in state advocacy for hydropower, oil and coal plants in India’s ‘frontier’ regions such as Assam and Kashmir. Though the histories of Assam, Kashmir and Dinetah (referring to Diné community envisioning of their homeland beyond settler boundaries) are vastly different, there are parallels in the ways in which settler colonial states use the discourse of modernity and development to lay claim over people and land categorized as frontiers or entry points to its development. The settler colonial imagination conceives indigenous lands as barren and empty places to be occupied for developmental projects. This perception of the Navajo Nation in Burnham, New Mexico saw Sithe Global Power pushing to develop the region through Desert Rock while in reality the benefits of the proposed energy infrastructure were distributed away from native communities. Challenging this settler colonial imagination through claims of Dinetah, Dine communities pointed out the reality of their homes as “a place inhabited by families, sheep, and vast desert ecosystems”(196). In contrast to the proponents of Desert Rock, Diné communities and specifically women (who exercise leadership over territory, and livestock) conceive their landscape as a place full of life

In my own project in Assam in northeastern India, tribal women similarly point out that hydropower projects located within their homelands create immediate disastrous impacts such as flooding and arsenic contamination while their own homes do not have electricity. Similarly, in Kashmir, northern India, women often actively resist state imposed hydropower plants which dislocate their communities and thwart resource sovereignty for women who require access to these resources to sustain their families (Bhan 2018:67-68). The adverse impacts of energy colonialism are thus felt by communities inhabiting these ‘frontier’ regions while the flows of energy move away from their own localities to be distributed elsewhere.

In my own project in Assam in northeastern India, tribal women similarly point out that hydropower projects located within their homelands create immediate disastrous impacts such as flooding and arsenic contamination while their own homes do not have electricity.

Indigenous studies scholar Mishuana Goeman talks about the interconnections between the destruction of indigenous homelands through oil pipelines, coal projects and hydropower projects and the accompanying dislocation and eradication of indigenous communities by settler states in the United States and Canada (Goeman in Barker eds. 2017:99-100). Powell further reiterates how gendered this destruction becomes as does the labor involved in sustaining life after settler destructions of lived environments. This is a point emphasized by Diné women’s personal testimonies in Landscapes of Power. They are often underrepresented in the Navajo nation’s tribal government and in the context of Desert Rock, they advocated for alternative energy sources such as wind and solar energy power plants which could create economic opportunities while also ensuring a sustainable source of energy for indigenous homes within the region.

Women across the three sites mentioned above: in Kashmir, Assam and Dinetah point out that energy infrastructure changes the constituents of the environment and land they inhabit, disturb sub-surface elements such as dust, uranium, coal which are ultimately responsible for the pollution of air and water, that further gets embedded inter-generationally in their bodies as contaminants. Landscapes of Power highlights Dine women’s advocacy for solar energy as part of a move towards sovereignty through a control over solar installations in their homes. The relative certainty of solar energy’s renewability is also emphasized in accounts such as Miriam Johns’, who lives in an off-grid home in the south-central region of the Navajo nation: “You never know what the future might bring – earthquakes or other things that might shut down the power lines. Now, I’m with the sun people”(108).

Powell’s Landscapes of Power brings to light through energy landscapes the historical and continuing settler dynamics of energy extraction.

Such accounts abound in Powell’s centering of Diné women’s understandings of their lived landscapes while an absence of these gendered views of the landscape in Navajo Nation official energy policies is also noted by community participants. These gendered dissonances in debates on an energy future have implications for the settler colonial logic of elimination which attempts to impose a heteropatriarchal logic of colonial discovery and dominance over indigenous lands. However, as Powell points out, the various voices and contestations of energy politics that emerge in the ‘boundaries of the American political system’(11), speak to the complexities of indigenous sovereignty and its intricate entanglements with settler colonialism.

Powell’s Landscapes of Power brings to light through energy landscapes the historical and continuing settler dynamics of energy extraction. Landscapes of Power traces the interdependencies between indigenous sovereignty and settler colonialism but also reveals that the settler state deliberately designs the double bind of needing to be recognized by the settler state while also refusing it. However, Powell’s discussion of the inherently exploitative nature of the settler state could have become even clearer through a greater exploration of gendered understandings of indigenous futurism, a concept that is briefly touched upon in Chapter 5 but is also present in Diné community dialogues, testimonies and art discussed across the book.

References

Barker, Joanne. 2017. Critically sovereign: indigenous gender, sexuality, and feminist studies. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bhan M. 2018. “Jinn, floods, and resistant ecological imaginaries in Kashmir”. Economic and Political Weekly. 53 (47): 67-75.

Goeman, Mishuana R. 2017. “Ongoing Storms and Struggles Gendered Violence and Resource Exploitation”. In Critically sovereign: indigenous gender, sexuality, and feminist studies, edited by Joanne Barker, 99-126. Durham: Duke University Press.

Read Lena Gross’ review here.

Read Susannah Crockford’s review here.

Featured Image by kasabubu, pixabay.com.