Why We Need to Talk about Referencing Creative Work

“I SUPPOSE you’ll manage.”

Chubby Sr. García, the regional military liaison with far too much dust in his cuffs, broke into a smile that marked him a persistent optimist. Still, his eyes hung a beat too long on the groaning pickup piled with plastic drums of contraband diesel, sacks of powdered milk and rice rebagged for trade, and his two hired hands—already called “the boys” without irony—set to guide us through mule tracks and mining trails to the informal encampment beyond the border crossing.

If you feel as though you’ve landed mid-story, good. That’s part of the point. This vignette is an echo, an imitation. A citational gesture that bypasses footnotes and instead borrows voice, atmosphere, and form. It’s an adaptation of the opening of Return to Laughter (1954), the anthropological novel written by Elenore Smith Bowen, pseudonym of Laura Bohannan. In her version, too, a white anthropologist is met by local intermediaries, their passage framed not only by physical terrain but by the psychic weight of the field. In our version, the coordinates have shifted and times have passed—but the structure remains, recast and reverberating.

Why begin here? Why this story, this tone, this trace of Bohannan’s work? Because this essay is about creative citation, and about the stakes of form—what we borrow, what we honour, what we let speak through us. The passage above is not an ornament. It is not a clever Easter egg for anthropologists who happen to have read Return to Laughter. It is an opening argument, delivered in the language of literary mimicry. It performs the very citational ethics this essay advocates: citation as entanglement, not extraction; as homage, not possession; as a quiet form of transmission that speaks to influence, resonance, and kinship between texts.

And yes, it’s disorienting. That, too, is deliberate. Creative work often is. Unlike academic citations, which promise clarity and legibility, creative references resist that neatness. They pull at something deeper: recognition, unease, curiosity. The discomfort here is not a failure—it is an opening. A way to signal that we are about to enter a conversation not about how to cite, but why to cite differently. And what becomes possible when we do so.

To name a creative piece is not enough. We must let it speak inside our work, shift our tone, fracture our arguments, delay our conclusions. We must let its rhythm interrupt our grammar

Return to Laughter was one of the earliest recognized attempts to smuggle the real contradictions of fieldwork—its absurdities, its ambiguities, its ethical failures—into narrative form. It turned anthropological knowledge into fiction not to fictionalise the truth, but to show how unstable, relational, and storied the truth always already was. We borrow it here not to revive a canon, but to unsettle it. To take that early experiment in form and let it resonate inside new terrain: a smuggling route, a borderland, a different kind of field.

This act of adaptation becomes a kind of ‘unfootnoted’ citation—a citation not of content, but of method. A way of saying: form matters. Mood matters. Lineage matters. What if our citational practices could hold all that, too?

So we begin here: with mimicry as a method. With a borrowed opening that neither claims nor conceals its origin, but lets it shimmer in a new context. From here, we will unfold what it might mean to reference creative work not just as evidence, but as atmosphere, rhythm, rupture. We will ask what citation might become if we allowed it to breathe. To echo. To feel.

And so we turn, slowly, toward the tangle. Because to cite is never merely to reference; it is to trace and retrace the filaments of an epistemic web, a web that binds and blinds in equal measure. Citation is architecture: scaffolding the edifice of legitimacy, holding up who gets to be seen as foundational, whose words endure, whose absence goes unnoticed.

These absences are not incidental. They’re structural, a consequence of how power circulates—who gets remembered, who gets misfiled, who gets called decorative, and who gets called theoretical. Citation is not only the history of ideas—it’s the history of exclusion.

In creative anthropology, these exclusions take on another texture entirely. Here, in the unruly zones of image, form, sound, and performance, the omissions don’t simply happen. They are built in. Experimental forms—films, visual essays, embodied ethnographies—are positioned as excess, as unruly data, as too beautiful to be serious, too serious to be beautiful. Their refusal to behave like “proper” scholarship—footnoted, static, expository—is met not with curiosity but suspicion. Their refusal is read not as rigour, but as rebellion.

And rebellion, as we know, is rarely rewarded.

The discipline polices its borders not just through what it includes, but how it includes. Rigour becomes a cudgel. Citation becomes a gate. The illusion is that knowledge is cumulative, tidy, traceable. But creative work reminds us that knowledge is also felt, fractured, uncontainable, confusing. Which is why it so often goes uncited—not because it lacks substance, but because it threatens the structure that pretends to define what substance is.

To be excluded from citation, in this context, is not just to be overlooked. It is to be overwritten. To have your work rendered illegible by the very system that claims to organise the field. Creative work makes a mess of that system—by design. And the system responds by pretending it never happened.

But resistance is not enough. Merely noting these exclusions doesn’t change their force. To cite creatively is not to add another line to an already bloated reference list. It is to rupture the list itself. In some cases to be referred to in context, but more importantly to ask: what if citation weren’t a ledger of obligation, but a map of resonance? What if it could be felt as well as read? This means we must reject tokenism—the performance of inclusion that leaves the canon intact. Because to cite a creative work as decoration, as diversity, as flair, is to gut it of its force. It is to remove its teeth.

Maybe that’s what we’re doing here. Trying to find a form—of citation, of voice, of relation—that can carry what we now know, and how we came to know it.

Citing creative work well—citing it with care—requires something else entirely. It asks us to approach not extractively, but relationally. Not as an illustration, but as an interlocutor. To name a creative piece is not enough. We must let it speak inside our work, shift our tone, fracture our arguments, delay our conclusions. We must let its rhythm interrupt our grammar. This is not simply about the politics of inclusion. It is about the conditions of knowledge itself.

When we do this—when we cite not just who said what, but how it was said, what it felt like, what it moved in us—something shifts. The edges of the discipline fray. New epistemologies become possible. The archive begins to breathe again. And so, we do not advocate for citation guides that tidy all this up, that create a new protocol for creative work and slot it into a bureaucratic footnote. That is not the point. The discipline doesn’t need more citation rules. It needs more citational courage. More citational experimentation. Which is why we offer two gestures. Not guidelines. Not policies. Just openings.

The first is imitation. That is, to cite through echo. Through a gesture, a structure, a line of light. Through mimicry that is not theft but tribute. This is what the opening of this essay attempted: a reshaping of Bohannan’s Return to Laughter not to steal her voice, but to sound it differently. Not to reproduce her narrative, but to press her form into new terrain. A citational murmur, not a shout. The second is to cite the creativity of a work—not just its data, its insight, its “takeaway,” but the mode of thinking that it makes possible. To reference not just what a work says, but what it does—how it moves, how it fractures, how it refuses. What follows will illustrate these approaches. They are imperfect. They will not suit every piece, or every reader. They are not systems; they are signs, suggestions. They point to a citational practice that is atmospheric, affective, and unfinished. That lives in gesture and texture. That trusts readers to feel their way as they go.

And if all of this started with Bohannan, perhaps it’s worth saying: Return to Laughter was never really about return. It was about what happens when you can’t go back. When the field changes you, and you’re left trying to find a form that can hold that change. Maybe that’s what we’re doing here. Trying to find a form—of citation, of voice, of relation—that can carry what we now know, and how we came to know it.

The Highest Form of Flattery is Imitation

Creative works resist the clean lines of traditional citation; they do not fit neatly into the footnotes and bibliographies that discipline knowledge into traditionally structured, manageable forms. They demand another kind of engagement, one that recognises their formal and affective force—not as ornamental supplements to theory, but as theoretical interlocutors in their own right. To cite a poem, a film, a performance in an academic piece is not just to name it but to acknowledge its force—to treat it as something that acts upon thought and feeling rather than merely illustrating it. In doing so, we enter a fragile but radical space, one where knowledge is not a fixed commodity but a living, shifting practice, one that changes shape with each encounter, each new presentation, each new reader, each new viewer. Before presenting the examples, it is important to be explicit about what is at stake. When we reference a creative work through imitation, we do not assume that every reader will recognise the original. Nor is recognition required. What matters is the encounter: the echo that signals a prior voice, the trace that invites curiosity. For those unfamiliar with the source, imitation should function as an opening rather than an exclusion. It should gesture toward another work, another way of knowing, and invite the reader to pursue it. In the examples that follow, the act of imitation serves not only as homage but as pedagogy — encouraging recognition where possible, and exploration where necessary.

The still below is drawn from Falling, the forthcoming essay film by Eva van Roekel that explores the ethical and emotional complexities of making cinema as an ethnographer engaged with individuals implicated in crimes against humanity in Argentina—military officers that many befriended interlocutors consider ‘genociders’. The film wrestles not only with its subject matter, but also with the question of form—how to shape a visual language that can hold such weighty film process. Scattered throughout are brief sequences and carefully composed shots that recall, without directly replicating, the seminal 1961 ethnographic film Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer) by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin. The resemblance is intentional, not as replication, but as a deliberate act of homage. The film draws inspiration from Rouch and Morin’s radically self-reflexive approach, where the process of filmmaking—its making, its mediation, and its reception by its participants—becomes part of the narrative itself.

Rather than quoting the original work in any literal sense, Falling engages in a kind of visual citation through stylistic echoes: the loose, observational camera work, the fragments of dialogue left hanging, the screening of rough cuts to their protaganists, the deliberate exposure of the filmmaker and its gear. Such visual gestures are common within the audiovisual lexicon of ethnographic and experimental cinema, where cinematographers and editors often ‘cite’ not through footnotes, but through composition, pacing, tone, and method. These are not just references—they are acknowledgements, forms of quiet recognition that express admiration for earlier works that have shaped their own ways of seeing their field sites through a lens. In this sense, imitation is not flattery in the superficial sense, but a deeper act of alignment and respect, woven into the very grammar of the film itself.

A similar citational strategy is at work in Adrie Kusserow’s prose poem NGO Elegy (2024), from her collection The Trauma Mantras. Kusserow does not merely describe the logics of humanitarian intervention—she channels their emotional and structural residue. The poem takes the form of an elegy not only for a colleague, but for the very idea of humanitarian knowing. Her language draws on the atmospheres surrounding aid work—its tensions, its contradictions—without resorting to its official lexicon. Instead of NGO-speak, we hear the fraying edges of a world shaped by it. She writes:

Thunder, rain, whole chunks of road gape open. usaid projects loosen, fall apart at the seams. Amid the pounce of rain, Taban, our night guard, bow and arrow at the ready, sleeps fitfully in the closet with the rats and frayed electrical cords.

To cite creatively is thus not simply to reference but to be moved by—to enter into a relational entanglement with the work, allowing its texture to unsettle the structures of argumentation.

The poem becomes a rupture—an ethnographic citation not through name or theory but through tone, mimicry, and emotional weight. Kusserow skirts the institutional voice, capturing its affective fallout rather than its vocabulary. It is a kind of imitation that mourns even as it critiques—a structural homage that exposes the limits and violences of humanitarian logics. To cite Kusserow well, we suggest, is not merely to reference her text in a bibliography, but to allow her method to shape our own. This may mean letting our academic writing hesitate, crack, or echo the dissonant rhythms of the worlds we study. It may mean slipping into a voice not entirely our own—letting its seams show, inhabiting its contradictions.

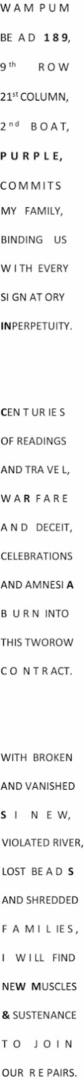

Also grappling with the haunting presence of historical institutions, Debra Vidali’s ‘Two Row Repair” is a trilogy of experimental ethnographic poems, which works through imitation of form in poignant ways. From her own position in the Hudson valley, and her own family history including 10 generations of Dutch ancestry in the USA, Vidali reaches for historical material forms that speak to questions of Indigenous sovereignty and allyship. At the centre of this, she takes an experimental approach to citing the first major peace agreement between Haudenosaunee and Dutch, in 1613: the Two Row Wampum belt, which represents a pact for peaceful coexistence woven out of purple and white shell beads.

The politics of ‘text’, and the hierarchies of knowledge, come into play in interesting ways here. Is the Wampum Belt a text? Vidali describes it as “a woven document,” but who is the author, and how exactly does she ‘cite’ this document? While she places a photograph of the belt alongside the poems – citing the Six Nations Library for this – the logic of imitation forms a much more radical and more forcefully present form of citation. Specifically, this happens through the shape (of two vertical rows) of the poems, and the angle and flow of reading it, which directly reference the shape and form of the wampum belt.

Vidali frames these poems as part of a journey of repair, and of decolonial praxis. They seem to do this in just the way we are discussing: with imitation functioning as an opening, or perhaps a bridge, across time and space, inviting the Belt into the present to shape (in the sense of a literal shape) her academic thinking. Just as the Wampum belt set to redefine relations between Haudenosaunee and Dutch, Vidali allows it to redefine the relation of words on the page, her relationship to the legacy of this poem. In this she names herself as “traveler, witness, descendant, signatory, collaborator, and rebuilder”. Which of these names might we also claim for ourselves, in choosing to cite this poem? How might doing so be contingent on not only gesturing towards it, but allowing for the possibility that we might reform ourselves and our texts in response to it, come into a different sort of relation, with and through it?

What Falling and NGO Elegy, and Two Row Repair all show is that imitation in creative anthropology is not decorative. It is a form of citational ethics that honours influence while transforming it. It makes visible the entangled genealogies that shape our thinking—through gesture, rhythm, image, and breath, and through the literal shape of text as form, vessel, and force. In both cases, citation is not about sourcing or verification. It is about what moves us and how we move with it.

To cite creatively is thus not simply to reference but to be moved by—to enter into a relational entanglement with the work, allowing its texture to unsettle the structures of argumentation. When we cite a film via imitation, we are not merely invoking its content but its modes of seeing and how it has been seen—the cuts, the repetitions, the gaps in speech, the spaces where silence does its work. When we cite a poem via imitation, we are allowing its rhythm to disrupt the cadence of our own writing, creating a field of tension where affect and analysis collide.

To cite in this way is to refuse the disciplining function of traditional citation, to refuse the idea that knowledge must be linear, stable, or resolved. It is also to value past creative interventions as living interlocutors—to make space for them to breathe again in new work. This kind of citation does not simply reproduce; it invites. It gestures toward future creativity by recognising its debts, by holding open the possibility that what has been made before might still be remade, revoiced, re-lived.

When the Work Thinks Back: Using Creative Anthropology to Shape Theory

To cite creatively is not merely to include a poem here or a play there—to tuck a verse beneath a theory and call it either evidence or resonance. It is to recognise when a work begins to think for you, with you, and even against you. It is to admit that what the creative piece does—its pauses, its density, its rhythm—is itself a kind of theorising. It’s a kind of theorising that doesn’t just explain, but makes and remakes—producing creative knowledge that emerges through gesture and form as much as through argument. The citation, then, becomes less about authority and more about allyship: not who you cite, but what kind of world–or way of thinking and feeling–you enter when you do.

Herein, we explore what it might mean to take creative works seriously as theoretical interlocutors. We offer a set of examples—not to be exhaustive, but illustrative—of how creative anthropological works, through their form as much as their content, challenge the boundaries of disciplinary knowledge. These are works that resist containment, works that pressure the sentence, fracture the paragraph, and trouble the conventions of academic prose. Our aim here is not only to showcase these works, but to demonstrate what it means to let them exert pressure on our own scholarly practice: to reshape how we cite, how we write, and how we think. This is a methodological invitation. To cite creatively is to enter into a relationship with the work that acknowledges its power to disturb, to reorder, to haunt. In doing so, we begin to trace a new citational politics—one attuned to form, feeling, and the insurgent force of creative knowledge.

We can see this clearly in the work of Zora Neale Hurston. Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is often shelved as fiction, but to read it only as a novel is to miss its radical ethnographic methodology. Hurston doesn’t simply describe Black Southern life; she writes from within it, giving narrative and linguistic authority to the vernacular, to oral storytelling, to Black women’s knowledge. Her work does not rely on the external gaze of the observer but emerges from an embedded, intimate knowledge—one that privileges voice, cadence, and situated ways of knowing. In a scholarly piece on gendered labour or Black feminist anthropology, we might be tempted to cite Hurston to “add texture,” to gesture toward cultural specificity. But that’s not enough. To cite her merely for context is to miss the theoretical force of her method.

Creative citation—when done with care—is not only an aesthetic practice, it is a political one. It resists the extractive tempo of the neoliberal university, where ideas are skimmed, sorted, harvested for use. In such a system, citation becomes currency, and knowledge a resource to be mined.

What if, instead, we let her narrative challenge our own narrative authority? What if we let the question be: What does Janie’s voice ask of my framework? What tensions does it introduce into the language I use, the categories I rely upon, the very shape of the argument I construct? What if Hurston’s form is not illustrative but argumentative—not a supplement to theory, but theory in action? To cite Hurston creatively is to enter into conversation with a form that challenges linear exposition, that insists on ambiguity and polyphony, that asserts practical knowledge through feeling, storytelling, and resistance. Such citation is to listen not just to what is said, but to how it is said—and to let that cadence shift the terrain of our own writing.

Let’s take another example, Gina Athena Ulysse, whose Because When God Is Too Busy: Haiti, Me, & the World (2017) doesn’t merely intervene in anthropology—it interrupts it. Ulysse moves at the nexus of poetics, protest, and performance, carving out a space where anthropology becomes something else entirely: affective, insurgent, embodied. Her work does not sit neatly in a citation; it flares and it fractures. To engage with Ulysse is to confront a refusal—not of knowledge, but of containment. Her poetics are volatile and urgent. Rage is not bracketed; trauma is not rendered digestible. The academic sentence buckles beneath her cadence. In “Why Haiti Needs New Narratives,” for example, she writes in fragments that defy the coherence of the neoliberal humanitarian gaze. Her performance VooDooDoll, staged repeatedly in both academic and public settings, combines chant, spoken word, and the sounds of mourning to stage a decolonial aesthetic that is as methodological as it is sonic.

In a conventional article—say, one examining the limits of objectivity or the violence of ethnographic extraction—Ulysse might be reduced to a footnote, cited as a critic of disciplinary orthodoxy. But that would miss the work’s method. She does not critique ethnography; she rewires it. Her poetry is not supplementary—it is the argument. Her voice is not background music—it is the archive, carrying histories in cadence and breath. To cite Ulysse properly is to allow her work to interrupt your own tempo, to let its rhythm unsettle the flow of your analysis. It is to slow down the academic pace and admit vulnerability into the prose. This becomes especially apparent in her 2018 performance at the British Museum, commissioned for A Revolutionary Legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture. Within the colonial walls of that institution, Ulysse did not simply present a talk; she invoked a counter-archive. Archival documents were not merely cited—they were voiced and embodied. Through poetry, personal testimony, and Vodou chant, she summoned histories of resistance and mourning, refusing to let them remain inert in the colonial record. Her performance wove together memory and defiance, transforming citation into a living, insurgent ritual. Archival documents were not referenced but voiced. Poetry, personal testimony, Vodou chant—they folded into one another in a ritual of insurgent memory.

In a scholarly piece on revolutionary memory, spiritual resistance, or the hauntings of imperial archives, Ulysse should not be quoted as ornament. Her work demands more. It requires a citational ethic that frees rupture onto the page, that allows silence, chant, and refusal to shape form as well as content. What if we let the ceremony interrupt our footnotes? What if we allowed untranslated phrases to remain as protectors of sacred meaning, not as gaps to be filled? What if we let Ulysse’s performance dictate our structure, our affective tempo?

To cite Ulysse is to cite rupture. It is to feel anthropology’s form shift underfoot. It is to let memory move not just through ideas but through bodies, rhythms, and wails. It is to treat anthropology not only as a mode of analysis but as a terrain of reckoning, reparation, and sound.

Laurence Ralph’s The Torture Letters: Reckoning with Police Violence (2020) offers another provocation. Like Ulysse, Ralph chooses a form that refuses the conventions of academic distance. Each chapter is structured as a letter—not as metaphor, but as method. A method of intimacy, of accountability, of ethical address. These letters are not illustrative anecdotes; they are the argument. They confront state violence not as case study but as wound, as relation, as unhealed historical trauma. In doing so, Ralph asks us to reimagine what constitutes evidence, and what form best carries its weight.

To cite Ralph, then, is to take seriously the letter as form: to write with rather than about. A traditional citation might extract his statistics or paraphrase his critique of the Chicago police. But that would sever that bare information from the affective and political labour his form performs. Instead, what if we paused, let the letter shape the tempo of our prose, or even echoed its voice in our own writing—taking up the mode of address, the vulnerability, the refusal to move too quickly past the pain? Ralph’s letters ask us to consider citation as witness, as call and response. His work is not simply to be cited—it is to be answered.

To borrow the form as well as the content of a creative work is thus not only a gesture of homage. It is a wager. A wager on the possibility that epistemologies embedded in rupture, opacity, and fragmentation can unsettle the architectures that have long underwritten knowledge as domination, extraction, and resolution.

Following Ulysse, who demands a citational form that breathes, Ralph demands one that listens. One that stays in the room. One that does not skim for data but sits with the discomfort of proximity. To cite Ralph well is to resist the detachment citation often affords. It is to let the structure of the letter—not just its content—intervene in our own form. To let its questions echo: What does this ethnography make you responsible for? Who is your work written for? And who is left waiting for an answer?

If Ulysse teaches us to breathe with a work, and Ralph teaches us to listen, Nomi Stone teaches us to fracture.

To cite the anthropologist-poet Nomi Stone is to traffic in both fracture and facticity. In Kill Class (2019) and Pinelandia: An Anthropology and Field Poetics of War and Empire (2023), Stone threads together verse and prose, fieldnote and incantation, to conjure the architectures of simulation that structure U.S. military training. Deep in the forests of North Carolina, mock Middle Eastern villages rise and fall; Iraqi role-players simulate insurgency; prop coffins wait for the day’s staged dead. The anthropologist moves not as an external observer but as an implicated presence—armed with a waterproof notebook and an Arabic phrasebook, attuned to the uncanny choreography of Empire rehearsing itself.

But this is not ethnography as conventionally understood. Stone calls this form “field poetics”—a designation that insists on the poem not as ornament or afterthought, but as method. Here, poetry is not a medium for distillation but a practice of disorientation. The verse unsettles. It stages the slippages, absurdities, and affective residues of empire’s rehearsals. As Stone writes:

“Say yes or no: if a man squints while

under the date palm; if a woman does not swing her arms

while walking. Sir, my child was not with the enemy.

He was with me in this kitchen, making lebna at home.”

(Kill Class, 2019: 3)

In Drones: an exercise in awe-terror, Stone pushes this logic further. The poem places us within the perceptual aperture of a drone pilot, training to see a world where everything is potentially a target. Yet—and this matters—the poem is not grounded in Stone’s own fieldwork, but emerges from interviews conducted by a close friend making a documentary for Frontline, a context Stone herself reflects upon in the accompanying essay here. The gaze that surveys “a sea of, a drowning of—everything seems / to be red rock. Prickling of dust and salt. / Seething, the sun between / the shrubs” is not simply descriptive—it is formative. The jagged sonic textures of the poem are not metaphorical representations of violence; they are its residue, its extension, its grammar. The body is asked not only to understand but to feel—to be implicated in the perceptual scaffolding of militarised vision.

Importantly, Stone’s invocation of “field poetics” enters an already articulated conversation. Zani first introduced the term “fieldpoem” in 2019 and reflected it in her moving and evocative book Bomb Children (2019). Stone’s practice diverges from Zani’s, and this difference is neither incidental nor oppositional—it is the material of the field itself: unsettled, plural, recursive.

So how might such work be cited in a conventional academic frame on militarism, simulation, or violence? One could extract Stone’s insight and paraphrase her critique of the “weaponisation of empathy” in military training. But to do so would be to defang the very charge that animates her work. To cite Stone well is not simply to quote—it is to allow poetics to intervene in analysis, to recognise enjambment, silence, and opacity as theoretical devices. It is to admit that anthropology’s conceptual tools are not always rational. Sometimes they are elliptical. Sometimes they rupture. Sometimes they grieve. Sometimes they deliberately refuse repair.

Paul Stoller’s ethnographic novel The Sorcerer’s Burden pushes these questions even further. Indeed to cite Stoller is to step into a space where ethnographic authority disintegrates into the haze of story, spirit, and speculative truth. In Stoller’s novel, the anthropologist does not simply report a world—he conjures it, stepping into the broken lineage of sorcery, migration, and filial debt. The novel stretches anthropology’s narrative contract: it folds possession into perception, memory into magic, kinship into epistemic fracture. Stoller does not use fiction to escape ethnographic rigour; he uses it to deepen it, to show how certain truths—sensuous, embodied, dissonant—cannot be rendered within the sterile grammar of conventional ethnographic form. If we are to cite Stoller well, we must allow for the burden he names to enter our own practice: the burden of knowing that knowledge is not only carried in reasoned prose but in dissonance, hallucination, hesitation, and ancestral call. In his hands, the novel becomes not merely a genre but an analytic: a method for attending to the unstable grounds on which our anthropological claims and observations rest.

To work with The Sorcerer’s Burden in academic scholarship is not simply to mine it for insights about migration, sorcery, or global entanglements. It is to let its speculative form and broken narrative logic press back against our own habits of representation. The work invites us to think with uncertainty rather than mastery, to acknowledge the spirit-worlds, obligations, and genealogical burdens that co-constitute the social worlds we study. Citing Stoller well would mean allowing for non-linearity in our arguments, recognising that sometimes ethnographic truths surface not in explanation but in haunting, in repetition, in the refusal of closure. It would mean treating the story not as illustration but as theory. And it would mean accepting that in the wake of empire and sorcery alike, the anthropologist may find themselves less a knower than a carrier—bearing a burden they can neither fully explain nor lay down.

What unites these examples—Hurston’s vernacular voice, Ulysse’s insurgent poetics, Ralph’s letters of witness, Stone’s field poetics, Stoller’s speculative ethnographic burden—is not simply that they are creative. It is that they blur the lines between form and argument, expression and evidence, experience and explanation. They force us to confront what we mean when we call something “theoretical” or “rigorous.” In each case, the formal choices are not incidental; they are the very means by which critique is delivered and knowledge is made.

To borrow the form as well as the content of a creative work is thus not only a gesture of homage. It is a wager. A wager on the possibility that epistemologies embedded in rupture, opacity, and fragmentation can unsettle the architectures that have long underwritten knowledge as domination, extraction, and resolution. In poetry, as in field poetics, rupture, silence, and metaphor are not aesthetic flourishes; they are analytic methods, sites where different senses of the real emerge. They do not simply adorn argument; they intervene in it, exposing the fractures it might prefer to smooth over, insisting on pointing to what cannot be contained, explained, or neatly systematised.

To let these techniques travel into our own writing is not to weaken scholarly rigour. It is to reforge it under different conditions. It is to shift the coordinates of what counts as rigorous: from the scaffolding of linear demonstration to the textures of interruption, resonance, and remainder. To move with fracture is to acknowledge that much of what matters—suffering, dispossession, refusal—cannot be known without also being unmade in the process of knowing.

Feeling, fracture, opacity: these are not failures of knowledge. They are modes of attending otherwise to a world already broken, already unfinished.

This section has offered a set of provocations—not a canon, but a call. A call to rethink how we engage with creative works in our scholarly practice. To cite such works well is not merely to quote them but to allow their forms to press back, to haunt, to reconfigure the architecture of our own texts at the largest and smallest grammatical level. To reconfigure our own way of thinking. It is to let rhythm interrupt argument, to let address reshape voice, to let metaphor redirect clarity. These are not acts of indulgence but of allyship—citational gestures that take seriously the political, methodological, and aesthetic stakes of creative knowledge. In citing them, we are not just referencing a work; we are entering and aligning ourselves with its world.

Conclusion: Citation as a Liberatory Practice

To rethink citation is to rethink the very conditions under which we are allowed to know, to remember, to speak as anthropologists. It is to ask: Who do we walk with? Whose cadence shapes our step? What do we carry forward, and how? Citation is not merely a scholarly apparatus; it is a declaration of allegiance. A tracing of kin. A cartography of influence, resonance, and refusal.

Creative citation—when done with care—is not only an aesthetic practice, it is a political one. It resists the extractive tempo of the neoliberal university, where ideas are skimmed, sorted, harvested for use. In such a system, citation becomes currency, and knowledge a resource to be mined. Creative works don’t perform well under such lights. They ask us to slow down. To listen again. To be changed. To cite creatively is to turn away from the logic of productivity and toward the logic of relation. It invites opacity. Dwelling. Feeling. It is not about reinforcing expertise but about refiguring intimacy. It asks not just what do you know? but how did you come to know it, and who moved with you along the way? It is not efficient. But then, neither is experience. Neither is healing. Neither is care. This kind of citational practice—through imitation, resonance, or formal entanglement—becomes a minor act of liberation. A crack in the edifice. A refusal to play by the rules of a system that primarily values what it can quantify. To cite creatively is to whisper: there are other ways of knowing, and they matter too.

We offer these approaches—these gestures—as openings. Not conclusions. They are imperfect, incomplete, and necessarily situated. But they point toward a citational politics that is not merely inclusive, but insurgent. Not decorative, but generative. Not merely about who gets named, but about what kinds of knowledge are made possible in the naming. In the end, citation is a story we tell about where we come from and who we owe. Let us tell richer stories. Stranger ones. Unsettling ones. Stories that resist the grammar of containment. Ones that borrow, echo, honour. Ones that allow Return to Laughter to become not just a text we footnote, but a form we reimagine. Not to return to it, but to let it return to us—differently, creatively, disruptively. Because the future of anthropology may very well depend not on how we cite—but on whether we are willing to cite otherwise.

Reference list

Bohannan, L. (1954) Return to Laughter. New York: Harper.

Hurston, Z.N. (1937) Their Eyes Were Watching God. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

Kusserow, A. (2024) The Trauma Mantras. Duke University Press.

Ralph, L. (2020) The Torture Letters: Reckoning with Police Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stone, N. (2019) Kill Class. Tupelo Press.

Stone, N. (2023) Pinelandia: An Anthropology and Field Poetics of War and Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stoller, P. (2018) The Sorcerer’s Burden: The Ethnographic Saga of a Global Family. UK: Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Literary Anthropology.

Ulysse, G.A. (2017) Because When God Is Too Busy: Haiti, Me, & the World. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Ulysse, G.A. (2018) ‘A Revolutionary Legacy: Haiti and Toussaint Louverture’. [Performance at the British Museum]. https://ginaathenaulysse.com/2018/03/performance-remixed-ode-to-rebels-spirit-or-lyrical-meditations-on-a-revolutionary-legacy/

Vidali, D. (2024). Two Row Repair: A Trilogy. Anthropology and Humanism, 49(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/anhu.12514

van Roekel, E. (Forthcoming) Falling [Essay film]. [Further publication/distribution details pending].

Rouch, J. and Morin, E. (1961) Chronique d’un été [Film]. France: Argos Films.https://www.imdb.com/fr/title/tt0054745/

This essay was written in the spirit of collaboration between Allegra Lab and Anthropology and Humanism and through the process of collective writing in alphabetical order by:

Ian M. Cook

Çiçek İlengiz

Fiona Murphy

Julia Offen

Johann Sander Puustusmaa

Eva van Roekel

Richard Thornton

Susan Wardell

Abstract: Citing creative work well—citing it with care—requires a relational approach. To name a creative piece is not enough. We must let it speak inside our work, shift our tone, fracture our arguments, delay our conclusions. Anthropology doesn’t need more citation rules. It needs more citational courage. More citational experimentation. Which is why we offer two gestures in this essay. The first is imitation. That is, to cite through echo. Through a gesture, a structure, a line of light. Through mimicry that is not theft but tribute. The second is to cite the creativity of a work—not just its data, its insight, its “takeaway,” but the mode of thinking that it makes possible. To reference not just what a work says, but what it does—how it moves, how it fractures, how it refuses. This piece accompanies the essay ‘Embracing the Art of Creative Review: Empathy and Dialogue’ and the guidelines ‘Reviewing Creative Anthropology’.