This book is a rich cultural analysis of how people live with big cats in India in times of the Anthropocene and climate change. As people are increasingly sharing space with big cats in India, anthropologist Nayanika Mathur asks: what does it mean to share space? What could beasts tell us about this? Specifically, this book focuses on the empirical questions: “What makes a big cat crooked? How do we humans come to recognize and intimately know a crooked cat?” (p.2) Based on her long-term fieldwork largely undertaken in the central Indian Himalaya and the city of Mumbai, Mathur approaches these questions around ways of living with non-human animals from multiple perspectives, and insightfully shows us how the complex human-animal relations can be articulated and unfolded, and furthermore how these relations are entangled with crucial issues concerning the political and legal regimes.

This book is a rich cultural analysis of how people live with big cats in India in times of the Anthropocene and climate change. As people are increasingly sharing space with big cats in India, anthropologist Nayanika Mathur asks: what does it mean to share space? What could beasts tell us about this? Specifically, this book focuses on the empirical questions: “What makes a big cat crooked? How do we humans come to recognize and intimately know a crooked cat?” (p.2) Based on her long-term fieldwork largely undertaken in the central Indian Himalaya and the city of Mumbai, Mathur approaches these questions around ways of living with non-human animals from multiple perspectives, and insightfully shows us how the complex human-animal relations can be articulated and unfolded, and furthermore how these relations are entangled with crucial issues concerning the political and legal regimes.

Chapter 1 attends to the various narratives that explain why and how some big cats become crooked. A key aspect of the human-animal relations in this book is uncertainty: despite a variety of explanatory accounts, big cats remain “unknowable and unpredictable” (p.8) in terms of why they become crooked. Yet in contrast to such uncertainty and unknowns, the state and conservationists act with certainty and follow rules that are based on certainty. Following this, Chapter 2 discusses a wide range of methods adopted by individuals and institutions to identify crooked cats. It contests these methods and shows that even “scientific” ways through an autopsy cannot prove certainty in identifying crooked cats. Chapter 3 describes a specific case where a white tiger gains popularity in the country, despite the fact that he killed a man; it shows “how specific named, known animals can and are cute-ified and acquire charisma” (p.77) As the last chapter on the government of big cats (p.22), Chapter 4 considers how affected citizens make efficacious petitions in order to demand the state action of catching or killing big cats. It conceptualizes what a petition is by outlining their various forms including the WhatsApp message and the human presence at the district office. Because the state is more concerned about protecting big cats than humans, humans, who also deserve protection from big cats, are placed in a vulnerable position. This chapter compels readers to ponder the critical questions that arise from the governance of big cats: “Who is the real beast of this tale? And how did we come to arrive upon this pass?” (p.93)

Yet in contrast to such uncertainty and unknowns, the state and conservationists act with certainty and follow rules that are based on certainty.

Chapter 5 attends to how human-animal relations are presented and narrated in fiction as well as fact-based stories. In doing so, it invites readers to think: what are the ways of narrating the beastly tales of crooked cats? Furthermore, how could we describe life in the Anthropocene? This is linked to some of the central questions of this book: how can we narrate stories of climate change? And how can academic writing intervene in the world (p.2)? Chapter 6 compares how people live with leopards in three different cities – Dehradun, Shimla, and Mumbai. This discussion is of great relevance to the current times in which due to the ecological breakdown, non-human animals increasingly enter and become regularly present in large cities which they used to avoid. Thus, how might we avoid conflicts with non-human animals and subsequently build peaceful co-dwellings? This chapter shows the possibilities of human-animal co-existence in urban space. Chapter 7 asks how the practice of using camera traps and other digital tools to catch images of big cats and further circulate them could shape and reconfigure the way we see and understand these non-human animals. In particular, it outlines the emerging legal as well as ethical questions around the copyrights and ownership of these images. Finally, Chapter 8 concludes with three tales, in which the key topics of this book, including the bureaucratic regimes and ways of living in the Anthropocene, are re-visited and emphasized.

This discussion is of great relevance to the current times in which due to the ecological breakdown, non-human animals increasingly enter and become regularly present in large cities which they used to avoid.

This book makes a significant contribution to multispecies scholarship by investigating the governance of non-human animals, which has been less explored by multispecies ethnographers. While studies on human-animal relations often face the critique of lacking attention to politics and issues of inequality, this book shows why these relations matter, and how they are relevant to the crucial structural questions and dialogues that concern bureaucracy, conservationist activism, popular cultures, and fundamentally, ways of living in the Anthropocene. The beastly intimacy is not innocent, but closely linked with issues of justice and violence. Furthermore, this book is deeply engaged with climate change and the ecological breakdown. Although it does not directly examine these concepts, this book proposes a new way of considering climate change by investigating how humans live with the predatory big cats. In doing so, it unfolds how climate change is understood and experienced in localized ways. Scholars with interests in human-animal relations, bureaucracy, climate change, multispecies ethnography, and South Asia, can greatly benefit from this book.

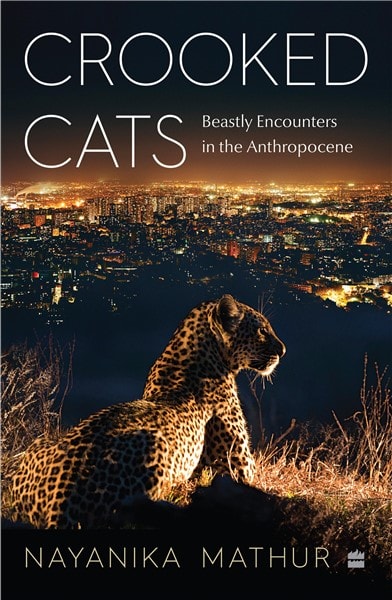

Featured image by Chris Mok || @cr.mok on Unsplash