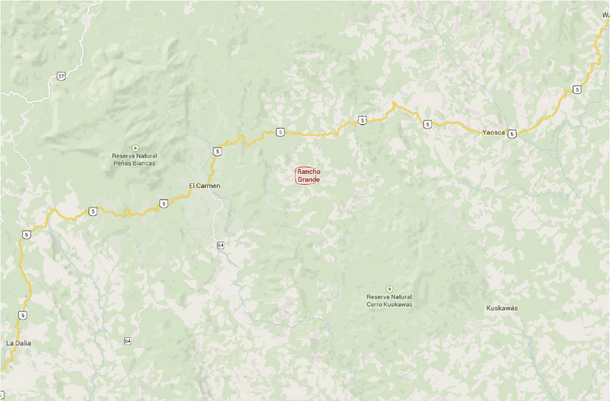

In October 2014, three yellow school buses with young anti-mining activists from ecclesiastic grassroots communities from all over Nicaragua ploughed their way through muddy roads, never ending lush valleys over dangerously narrow bridges crossing rushing waters to reach the small town of Rancho Grande in the North of Nicaragua that has been designated to become one of the centres of open pit gold mining. Here beautiful old trees shade coffee and cacao bushes of all sizes interspersed with banana plants, yuca, malanga and the occasional cornfield with mature cobs. The fertile valleys of Rancho Grande are among the breadbaskets of Nicaragua. When other regions are affected by drought, food continues to grow here.

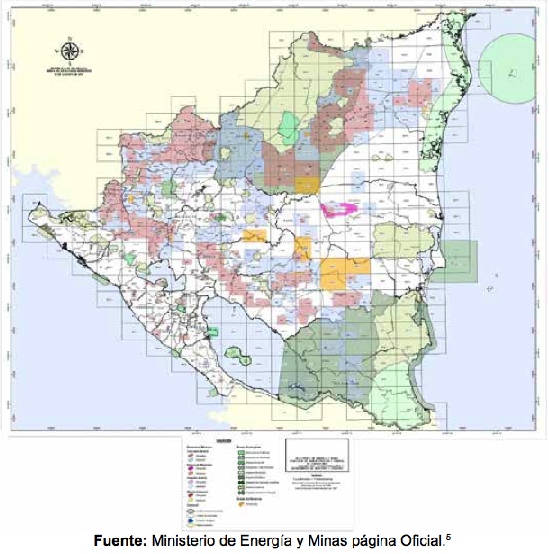

This lush paradise is in danger now that the Canadian mining company, Vancouver-based B2Gold, acquired gold mining concessions in the area (1), buying up the joint venture between the Canadian Central Sun Mining and the Nicaraguan company Minesa. The planned open pit mine in Rancho Grande is on one of 54 metal mining concessions that the Nicaraguan government has granted, six since 2011. Although the number of concessions has not increased dramatically, the concessioned area has increased by 29,77% over this time and gold production in Nicaragua has more than doubled from 168.197 thousand troy ounces in 2009 to 473.145 in 2013. (2)

Since 2004, Canadian mining companies in cooperation with Nicaraguan enterprises have explored for gold in this area. For four years, successive mining companies have tried to buy up land in the area, while the ranchers, coffee growers and small farmers struggled to keep them from their land. (3) 49,000 hectares around Rancho Grande fall within the mining concession, which has been granted for 25 years, including the nature reserve Las Aguas and the majestic Cerro Grande from which most major rivers of the region begin, in particular the Yaosca river. A researcher at the Centro Humboldt remarked that although mining is still in its exploratory phase in Rancho Grande, they have found that fish in the Yaosca river have become so contaminated that they are non-edible. The Yaosca River borders the Nature Reserve Macizo de Peñas Blancas. (4)

Gold mining is one of the most inefficient and most polluting extractive activities known. From one ton of earth dug up with huge machinery only one to five grams of gold are extracted, leaving a landscape of devastation, pollution and destruction. In 2013, however, gold became the main export commodity of Nicaragua, surpassing both beef (US$389 million) and coffee (US$349 million), according to the Centro de Tramites de las Exportaciones (CETREX). With B2Gold in the lead, mining companies exported nearly US$436 million worth of gold, a new record, despite a substantial drop in the commodity’s selling price.

The industry’s overall contribution to the economy, however, is deceptively small: mining employs just 2.2% of Nicaragua’s eligible workforce and represents only 2.5% of the Gross Domestic Product, states a 92-page report from the Centro Humboldt. (5)

Ecclesiastic grassroots communities from around the country chose Rancho Grande as this year’s venue for their third environmental folk festival on the 11 and 12th of October 2014 to attract media attention to the local struggle against open pit gold mining. The local mayor and governing Frente Nacional de Liberacion Nacional (FSLN), however, continue to present mining projects as an economic blessing and an export success. They brought in mine supporters from mining towns as far away as Siuna and Waslala to demonstrate their support. Fortunately, a convoy of thirty buses and lorries carrying mine supporters were on their way home when the yellow buses with the mine opponents approached the last river crossing. Direct clashes were avoided and shortly before nightfall the activists arrived at the Catholic Church where the local chaplain welcomed them with a warm meal.

A succession of local catholic priests has been instrumental in informing the Rancho Grande population about mining and supporting their protests. When the mining company found gold after eight years of exploration and wanted to convert their exploration permit into a permit for exploitation in 2012, Father Theodor Curtis preached against the environmental destruction that would follow. In the tradition of Monsignor Romero of El Salvador, he urged the inhabitants not to give their consent to a project that would destroy the basis of their livelihood.

According to Nicaragua’s environmental legislation, the local population has to be consulted about energy and mining projects, although failure to obtain consent is not legally binding. The exploitation phase has not yet started.

In lieu of a public consultation process and in order to drum up local support, B2Gold started to distribute zinc laminas for roofing, chickens and pigs, rubber boots and machetes. When Father Curtis warned the local population that they were being cheated, the company started to use more sophisticated measures and local authorities started to find ways to obtain signatures from local residents. When poor families signed up to receive food parcels from local authorities their signatures were used in support of the mine. “They play with the misery of the human beings. People who have absolutely nothing are cheated more easily,” one of the local leaders told me. A drinking water project was started and inhabitants who signed up for it had their signatures counted in favour of the mine. A health worker who did not dare to join the event told us that health workers, teachers and other public servants were coerced to give support to the mine in order to keep their jobs. Sandinista members of the municipal council who objected to the mine were asked by the FSLN party to resign.

The large majority of the inhabitants of Rancho Grande and of the surrounding villages, however, remain opposed to mining. “We are the 95%, only five per cent are in favour,” a local leader said. Numerous members of the evangelical church refused to follow their pastor who is a strong advocate for the mining company. In 2013, parents from all the 38 surrounding communities organised a school strike in opposition to the mine in 45 schools and nine marches in protest.

The first night of the environmental folk festival, a stage was set up outside of the Catholic Church and, as the music began to play, more and more people came in from the streets. The youth groups from different regions of Nicaragua performed folkloric dances in colourful costumes to Marimba and Costeña music that had inspired the Sandinista Revolution in the 1970s. Short theatre pieces alternated with prayers and calls to resist the mining companies that “toy with the lives of the people”. Over and over the motto of the movement resounded: “Quien tiene un amor grande defiende a Rancho Grande!” (Those who are capable of great love defend Rancho Grande!). The speeches explicitly situated the resistance to mining in the much longer tradition of 522 years of resistance to colonization, exploitation and oppression. Also, the revolutionary spirit of older generations who were up in arms thirty years ago was revived. They evoked Sandino, the love for the land and liberation theology.

Not even the rain that started to pour diminished people’s enthusiasm as young and old drew closer and closer to the stage fusing with the performers in a single wave of joy.

After the celebration, wet and tired, younger activists slept on church benches or on the floor, while local residents offered older ones a bed. Early the next morning, the church was packed with peasants who in some cases had walked for hours to join the service held by Father Pablito Espinoza who preached with fervour for the courage to defend the rights of the poor and against fear. “I received death threats”, he said, “I was told ‘Father, you are going to die’ — ‘yes of course’, I answered them. I told the mining company, ‘if you have any dignity left, leave Nicaragua’!”

The company B2Gold, however, continues to buy up land, often hiding its identity behind third parties or government projects. Local residents suspect that 5,000 manzanas (about 3,522 hectares) of land that a government commissionaire wanted to purchase on Cerro Grande – supposedly for reforestation – was in fact a cover up, as Cerro Grande is still covered with old growth forest. Instead of 5,000 manzanas, government agents have been so far able to acquire only 1,500 manzanas (about 1,050 hectares), given that locals refused to sell. Barbed wire and army units secure the exploratory pits. The earth extracted from 150 metre deep exploratory wells is washed with cyanide in plastic lined pools, so called pozas de cola. People who walk after night on the road close to the pits are stopped and interrogated.

“We don’t have economic power, we only have tenderness”, the speakers in the closing rally rang out. “The bad have everything and the good have so little.”

While Sandinista youth groups threw firecrackers, loudspeakers played looped recordings of a speech in favour of the mine to try to drown out the speeches at the meeting. One unperturbed activist declared: “This fight has no party flags, no race, no confession. The yes or no to this mining concession depends on us here in Rancho Grande.” Although Father Espinoza tried to hold back protestors from going into the streets of Rancho Grande because they had been unable to obtain authorisation to demonstrate, people held a short march through the town to show that they would not allow the government, in the words of one old man, “to oppress our rights.” When the three buses began the return trip of their precarious journey, they once again encountered the buses and lorries of mine supporters from outside.

In official Nicaraguan media, only these officially orchestrated marches on October 11 and 12th that any received attention. The view that foreign investment in gold mining brings environmental destruction rather than positive benefits, which inspired local protests, did not fit with the outlook of either Sandinista nor of Conservative newspapers. Cut off from national media and without internet access, the inhabitants of Rancho Grande, however, have a clear idea about Canadian investors. As one farmer said: “They do not care whether our water is contaminated. A foreigner, he is not interested in our lives. And I wonder: If I were to pee in a public space in Canada, they will put me in jail, won’t they? What would they do to me if I did all they are doing here? […] Why don’t they respect our water? Why don’t they respect us as human beings?”

Canadian mining companies can act with impunity in this remote corner of Nicaragua where courageous men and women fight an almost impossible fight for their land, health and future of their children. It is now up to the Canadian public to do their part and call the Canadian companies and authorities to account as to why they are going ahead despite strong local resistance in Rancho Grande.

Notes:

1) http://www.centralamericadata.com/en/search?q1=content_en_le:%22B2Gold+Corp.%22&q2=mattersI nCountry_es_le:%22Nicaragua%22 [accessed 21.11.2014]

2) Centro Humboldt 2013 Estado Actual del sector minero y sus impactos socio-ambientales en Nicaragua, 2012-2013 (Current state of the mining sector and its socio-environmental impacts in Nicaragua) page 25 [accessed 21.11.2014]

3) http://www.addac.org.ni/videos/10-la-mineria-una-nefasta-realidad-para-rancho-grande/ (accessed 3. November 2014)

4) Ministerio de transporte, Valoracion ambiental: p.23

5) Centro Humboldt 2013 Estado Actual del sector minero y sus impactos socio-ambientales en Nicaragua, 2012-2013 (Current state of the mining sector and its socio-environmental impacts in Nicaragua) [accessed 21.11.2014]