This month, Chileans will decide whether to set in motion a process to change the country’s dictatorship-era constitution while marking a year since the beginning of a popular uprising only temporarily stalled due to Covid-19. In this context, change remains a simultaneously mundane and spectacular phenomenon as it lingers everywhere in the air.

*

I kicked off the year 2020 in a small house on the outskirts of Santiago de Chile. There were just five of us there, a small familial gathering plus me, someone who had just come back to visit after a five-year absence. We had pisco drinks and home-made pizzas that we shared standing around the kitchen. We talked about travels and climates and just a little bit about politics. A few days earlier, a friend and I had gifted each other lucky yellow underwear to be worn on this evening to ensure prosperity in the new year. I had left my pair upstairs, both unworn and unwashed since its journey from the factory to the street vendor’s stall to my tote bag to my mess of a still half-unpacked suitcase. Other rituals were, however, carried out with care. Following Danish tradition, we jumped into the new year from couches and chairs at the stroke of midnight to avoid slipping into the crack between then and now. Then, we each filled a small backpack with a few randomly selected objects and exchanged cash among us before embarking on a walk around the neighbourhood, pesos in our pockets and some light luggage on our backs. This would, I was told, mean a new year full of monetary gains and adventures in travelling. None of the neighbours who had come out with their kids to play with confetti seemed to find our rather idiosyncratic procession particularly strange. We stopped to chat, the mood was light.

2020 did not turn out quite as we hoped it might. There has been no abundance of money nor travel. It has been difficult to keep the mood light. Pandemic twists and turns aside, this year has seen continued calls for change leading up to Chile’s October 25 referendum on constitutional change—originally planned for April—and, somewhat expectedly, an excessive government response in the form of teargas, rubber bullets, and more. In Santiago as much as in the rest of the country, the new year arrived in the midst of a social uprising. Since October of last year, protesters had made waves far beyond the newly dubbed Plaza de la Dignidad, the epicentre from which demands for a more just society had been extending outwards ever since a rise in Santiago’s public transportation fares tipped a cup that had been filling with almost-final drops for some time.

*

As has been pointed out by many since then, the changed fare pricing was merely a very small tip on a very large iceberg that had been looming underneath the surface of Chilean society for many years. With a constitution formulated during military rule still in place, large parts of the Chilean population continue to come up against politically imposed barriers that uphold pervasive socio-economic inequalities. This uprising, then, quickly came to embrace various overlapping causes, concerns, and visions for the future. It also brought out the viciousness of the police force and the authorities overseeing their work.

This uprising, then, quickly came to embrace various overlapping causes, concerns, and visions for the future. It also brought out the viciousness of the police force and the authorities overseeing their work.

In the last year, thousands have been hurt during protests. Before the end of 2019, hundreds of people had suffered horrific and life-changing eye injuries as a result of shotgun pellets fired by the police force, the so-called carabineros. In early October this year, as protests were intensifying in the weeks leading up to the referendum, the state-sanctioned violence seemed to reach new heights as a young man was forcefully pushed by a carabinero from a bridge into the shallow Mapocho river below, falling head first with hardly any water there to soften the impact. Caught on camera, the officer in question has since been detained on suspicion of attempted murder. However, despite widely shared images evincing otherwise, police authorities have maintained that the 16-year-old simply fell over the side of the railing.

Well before the arrival of Covid-19 brought things to a lull for a time, goggles and face coverings were already a common sight in Santiago, protecting not against viral contagion but against other undesired presences spreading through the air: bullets and teargas.

At the same time, during my visit, the protests and the undercurrent of discord that spurred them on seemed both omnipresent and, at times, distant. Along the streets around the Bellas Artes metro station and down through the adjacent neighbourhood of Lastarria, young people—some alone, some in pairs, and some in small groups—filled the sidewalks with an assortment of little things laid out on blankets for sale. Some were vending old clothes, others new homemade garments that might have made a small but not insignificant profit. Others still sold jewellery, packets of incense, and other diminutive goods alongside more seasoned vendors who offered up used books from stalls that served to lift their business up from the pavement. Right in the heart of the neighbourhood, a photographer was selling homemade prints in varying sizes. His photos all depicted scenes from the protests of recent months, allowing passers-by and potential customers to see with their own eyes the spectacle of events recently transpired, albeit it a one-dimensional spectacle at a relatively comfortable distance from the real deal, still playing out just a few blocks away. No matter where I went, it seemed, there was no escaping reminders of the antagonisms that seep through the post-dictatorial city.

*

A few days into January, I had gone for a drink with some friends. Enjoying the pleasant warmth of the early evening and having decided to stay outdoors, we sat around a wooden table in a popular courtyard-turned-bar, sipping salt-rimmed pints and sharing snacks while surrounded by walls covered in ivy and groups of people talking and laughing at the tables around us. Soon enough, however, another presence made itself known. It started as a slight itch, like a sneeze coming on. Soon it felt more like a peppery irritation of nostrils and eyes. Looking around, I could see people at the other tables beginning to hold their noses or otherwise cover their faces. Looks were exchanged and a few giggles passed around between the tables.

The timing seemed about right. Somehow the inflow of teargas had been surprising and expected at the same time. It being the early evening, the daily round of protest would be kicking off down the street at Plaza de la Dignidad. It was only logical that teargas cannisters would be flying through the air, their contents blowing with the breeze in our direction. The smell and discomfort of the teargas were visceral reminders of the constant vicinity of (potential) unrest. Their presence in the setting of a cosy patio bar somehow also took the edge off the threat they represented, as if we were all aware that we were protected, at a distance from trouble in our walled enclosure.

The smell and discomfort of the teargas were visceral reminders of the constant vicinity of (potential) unrest.

Most likely, not much would have been happening by way of riots or disturbances of any possible peace down the road at the square. Just an hour or two earlier, I had been passing time in Parque Forestal, a stretch of urban green leading up to Plaza de la Dignidad. I sat on a concrete bench overlooking an impromptu art installation comprised of oversized cut-out cardboard eyes hanging from the trees; a reference to the targeting of eyes by state-authorized shotgun-carriers. Reading and soaking up a bit of afternoon sun while waiting for a friend, I was interrupted by the familiar sight and sound of a water cannon slowly rolling around the block while intermittently blasting water in the direction of anyone around.

The water cannons, known as guanacos in local parlance, were no unfamiliar presence. And in some ways, it seemed as if the purpose of this particular guanaco lay in its very presence. Had it been deployed simply as a reminder that violence was not only a constant possibility but in fact something quite likely to occur at the hands of authorities? In either case, the guanaco’s work seemed largely ineffective, both as a source of liquid assault and as a purveyor of fear. There were no crowds and nothing even remotely resembling what some might term riotous behaviour. I saw water, but it was flowing down the street, not dripping off protesters. People strolling through the park at a safe distance continued to do just that, the scene failing to raise neither alarm nor eyebrows.

Nonetheless, I felt the urge to warn my friend of the potential danger of passing through Plaza de la Dignidad on his way to meet me. “I see the guanaco in the plaza,” I wrote. “Always,” he responded. “Be careful,” I added. “Always,” he responded.

A couple of days later, I was walking past the presidential palace at La Moneda when I came upon the guanaco once more. Rather than an ominous presence, this time the water cannon was the unlikely star of an awkward scene. While a few passers-by stopped to point and film, the water cannon was being slowly and painstakingly manoeuvred around a narrow corner. A couple of uniformed carabineros assisted from street level with waving hands while the bulky vehicle rolled forward, came to a halt, rolled back, turned a bit, rolled forward, came to a halt. It looked bruised and battered with an air of defeat. The sun was shining, the street was almost quiet. I carried on and ordered lunch at a sidewalk café.

*

Despite viral interruptions, the wheels of change have kept turning since then. Indeed, in this context, the pandemic has only highlighted the very issues protesters set out to call attention to in the first place. Soon after Covid-19 made its way to Santiago, videos showing people crammed together on public transportation on their way to work began circulating. For the working poor, there was no working from home, no avoiding the rush hour commute, even during a pandemic. Unequal access to decent healthcare remains a major grievance and a symptom of a political system many consider sick.

Indeed, in this context, the pandemic has only highlighted the very issues protesters set out to call attention to in the first place.

Meanwhile, as lockdown measures were put in place, President Sebastián Piñera took the opportunity to pose for photos in an empty Plaza de la Dignidad, marking in no subtle way his supposed success in dismantling the movement for change. Of course, although he had declared a state of emergency and claimed to be “at war” already at the outset of demonstrations in October 2019, it was the onslaught of a pandemic rather than his deployment of police and military forces onto the streets of the city that had afforded him this temporary victory.

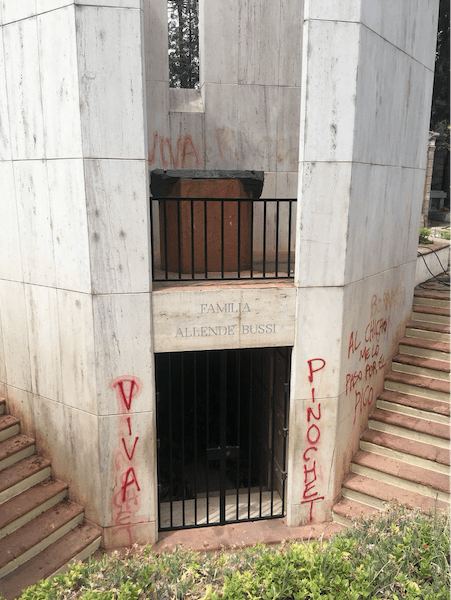

Nonetheless, to assume without further ado that a majority of voters will decide to work towards a new constitution on October 25 would be a mistake. A couple of days before my second encounter with the guanaco, at the large Cementerio General, two workers could be found sweating in the summer heat while cleaning pro-Pinochet graffiti off Salvador Allende’s tomb using the combined power of a high-pressure hose and elbow grease. “VIVA PINOCHET” read the bright red lettering splayed across the back of the tomb, which the two workers had yet to reach. To the front, only a wet shadow of the original intervention remained. A bit further up the path, three young people dressed in all black were carrying out a discreet photoshoot among the dead, two of them sombrely embracing in front of the camera with the bright sun lending a fitting ambiguity to the gothic scene.

*

In Santiago, the potential for state violence has long coexisted with an everyday in which guanacos and carabineros sometimes seem unremarkable features that warrant no particular reaction or change in behaviour, and where voices for change mingle with those who still speak of the past with nostalgia. Seeing the guanaco facing the obstacle of a narrow corner took away some of its symbolic power and simultaneously highlighted just how banal the machinery of repression is. Being the sole witness to the slow removal of pro-Pinochet graffiti on Allende’s grave underscored not only how the spectacular and the mundane coexist but how deeply these are entangled with one another.

In Chile, the issue of (constitutional) change is at once pressing and long-awaited, felt through bodily reminders—in people’s faces, their noses, their eyes—and at times experienced as a present reality only at a comfortable distance. It is in the noise of chants and shouts at Plaza de la Dignidad and in the quiet of the cemetery. On October 25 we will find out how it presents itself on the ballot.

Featured image by Javier Collarte courtesy of Unsplash.