Anthropologists have traditionally been artifacts (the products of man) collectors. This is the reason why Allegra felt compelled to open its own Virtual Museum of Obscure Fieldwork Artifacts: to exhibit the marvelous objects anthropofolks have brought back from their various fieldworks around the world. But Allegra would not be Allegra without the pinch of self-irony that characterizes our online experiments. Indeed, our artifacts humourously distort the ‘mysterious’ and the ‘exotic’ that tends to dominate in narratives of classic ethnographic museums. They nevertheless offer windows into our own belief systems and the belief systems of ‘others/alter-egos’. They are material entry points into traditions of craft and reflect societal needs or the state of technological advancement of a specific time.

An artifact can have numerous definitions. In anthropology and history, the typical definition is that it is a product of some society, usually intentionally made by someone in that society. These can be ancient things, like Ming vases or soapstone carvings, or they can be fairly recent. They may be defined as being at least 25 years old, though people may be used to thinking of them as much older and from societies in the distant past.(…) Artifacts help create pictures of a society. The pictures are often incomplete, and new finds from the same society may completely change the way historians or archaeologists view it. (Source: WiseGEEK)

In the spirit of continuing our reflection on the role of ‘artifacts’ both within our discipline and in cultures and societies more generally, yesterday we introduced Amanullah Mojadidi and the ARTifact project he ran with Noah Coburn‘s students at Bennington College. Today, we share with you the artifacts students collected/created as well as some of their reflections on the process of representing the ‘culture of others’.

ARTifact #1

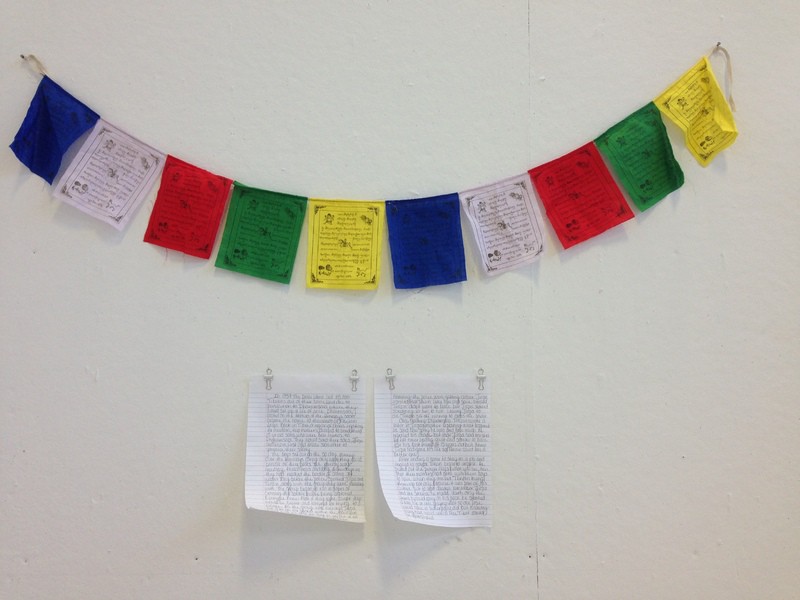

“Aman’s workshop was incredibly interesting and enlightening. Our task was to create or find an artifact and then give it a history or a story. Some people made their artifact out of found objects while others brought in objects they had and built a story around that. What I found most beneficial and informative was going through the process. I started by finding some tiles in the dumpster of VAPA. While collecting the tiles and thinking about what story I could come up with to represent them as an artifact, I found that I wasn’t totally invested in this idea. At the end of our first day, I thought more about a topic and artifact in which I might feel more passionately about. I had prayer flags hanging in my room from when I went to work with Tibetan exiles in Dharamsala. I decided to use those as my artifact and build a story about them.

“I had been told a story about a boy who made the 30-day journey from Tibet over the Himalayas to Dharamsala. They were on their way when the police started chasing them and his friend fell into an ice pocket in the mountain. He had to leave his friend behind to die so he could save himself.

What I found most powerful about the experience was the process. This is what Aman stressed the most, and it truly was the most important part of the workshop. I wasn’t feeling passionately about my first idea, so I found something that had much more meaning to me. It was a process of finding something that had significance to me and making it a personal experience.

ARTifact #2

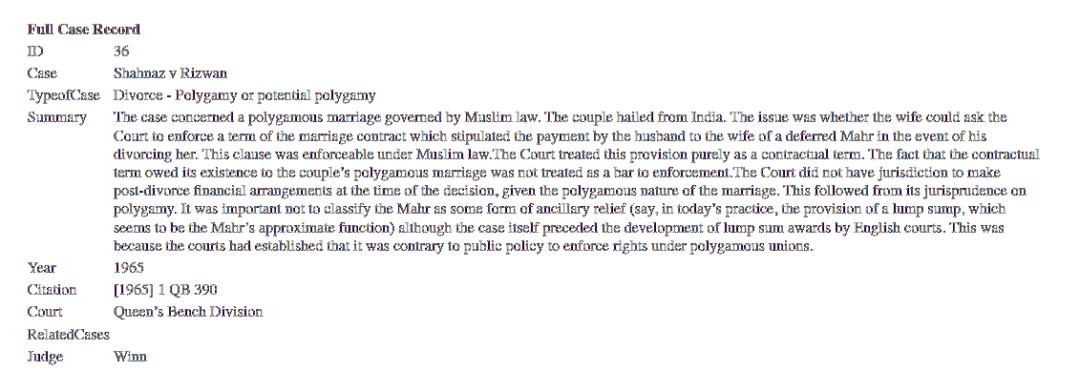

“During the 2 day workshop (March 1st and 2nd) we were asked to create artifacts in relation to a social or anthropological event and its connection to current events around the world and how that can raise a controversial opinion on what meaning it holds. I chose to create a factual-fictional story about a journalist who was brought up in Afghanistan, then created a wave of political public involvement in order to provide more rights using the law through his writings. He gets through troubles with the law then gets exiled to France where he develops a bigger sense of responsibility towards the public and develops a wave of anti-government writers to change the rights of the public and religious minorities around Afghanistan. With his new ideologies and strong opinions he becomes a person of great power and strong words. After his return, he was assassinated by the Afghans who then changed constitutional articles about freedoms of expression and press in order to restrict these freedoms even more after the public movement toward a free spoken Afghanistan.”

“Looking at the works of Aman and connecting those to the stories of authoritarian power and control over the public gave me the inspiration to create the artifact of the remains of the assassinated journalist and write his story in order to show the struggles in third world countries like Afghanistan.”

The artifact consisted of a previously made ceramic backbone that was placed on a block of wood, and that was then placed next to the historical story and the segments of the Afghan constitution that were connected to the story.

ARTifact #3

“Coming to the Bennington Museum in 2257, Vermont Zen Center member Benjamin Ehlers gathered inspiration from Coffee Cup to create his photo print showcased here. In specifically noticing the holed out bottom of the cup, Ehlers created The Hungry Ghosts and The Thirsty Spirits, submitting it to the museum to showcase in its Vermont Artists exhibition. Drawing specifically from the Buddhist scriptures, these ghosts and spirits dwell in the six worlds and are never allowed relief for their endless desires. The Hungry Ghosts and The Thirsty Spirits show cases an era of consumption in which desires and ultimately addictions may never be satiated.”

ARTifact #4

“Globalization doesn’t just happen on the political level, but socially as well. Particularly in the digital age, interconnectedness between individuals on platforms such as Facebook has resulted in a shift of societal power. Through this, people are given more power while also conceding a great amount to a collective mindset and a “mob mentality” outlook with pop culture. Therefore, I created a parody of Facebook and how this phenomenon will be perceived in the future.”

ARTifact #5

“Realizing the power curators of museum exhibitions wield through my own invention of artifacts was illuminating. The process of ascribing meaning to a history with both fabricated qualities and authentic qualities gave me the opportunity to put a narrative into the world that I judged to have value and merit (even if our micro-world in VAPA was invented).”

“During Aman’s workshop I chose to create artifacts linking American Suffrage Movement icons Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Lucretia Mott to the six Iroquois nations. The matriarchal or Mother-Clan system imbedded in Iroquois culture did directly influence the work of these prominent women during the mid-late 19th century (I didn’t even have to make it up, real history was crazy enough). Matilda Joslyn Gage even became a full member of the Mohawk tribe’s wolf clan after being arrested for casting a vote in a school board election in 1893. I decided that this was exactly the type of story I would want hanging in a museum.”

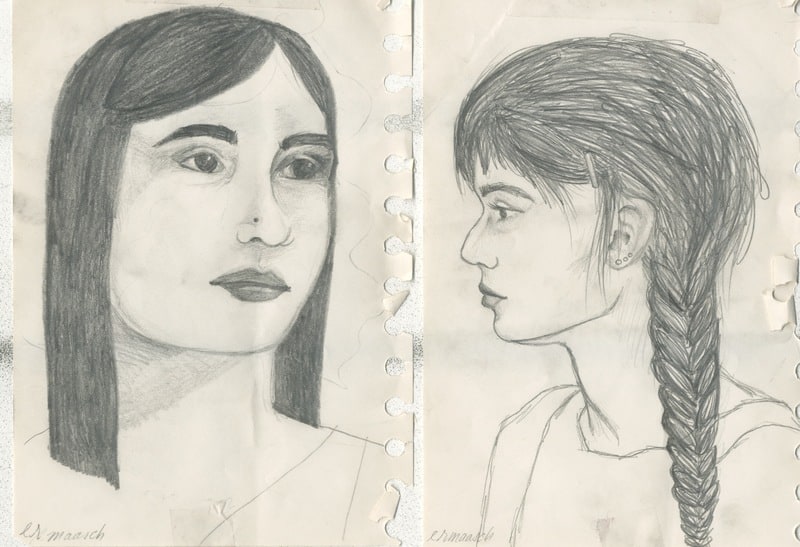

I wonder why the connection between suffrage and the Iroquois is obscured, and what a modern young Iroquois-American feminist would look like. In my reflective sketches, I attempt to create my image of what this identity could look like. Aman’s workshop definitely has me redefining what I believe the institution of a museum is responsible for, and what my potential role could be as a patron or participant within a museum setting.

“The authority a museum holds is one of the key elements at play in convincing patrons what is both history and fact. An instrumental facet of Aman’s workshop was the culminating act of placing each student’s artifact in a museum/gallery like setting in an attempt to replicate the institutional feeling of walking through the cultural artifacts section of the Museum of History and Natural Science. A gallery space in Bennington’s Visual and Preforming Art’s building was reserved b Noah Coburn.”

ARTifact #5

“In Aman’s workshop we were presented with the task of constructing or curating an artifact and then prescribing it an invented or adulterated history. With this prompt, I fabricated a display of an “anato-pig” and developed a mythical scenario justifying it’s history as an artifact, that would address themes of censorship, intellectual freedom and education. Thank you to Aman for the incredible workshop.”

Listen to the soundtrack for ANATO-PIG!

About Anato-Pig:

Originally used in the mid 2100’s for educational purposes, the anatomical pig (anato-pig) was commonly found in primary public school classrooms throughout the United States. From 2110 when it was introduced to the market by the schoplastics corporation to the late 2140’s, the anato-pig was used ubiquitously by public school teachers in biology, health, and sexual education classrooms. Following the regime’s outlaw of models that displayed the human body, the anato-pig became the most popular demonstration doll among administrator’s of state institutions. At the height of it’s popularity the anato-pig had become such an iconic character for schoolchildren that it often made appearances in cartoons, particularly state-funded propaganda reels where the anato-pig was often portrayed in the “good citizen” role.

During the revolution the anato-pig became a symbol of the intellectual oppression that the rebels were fighting against, the majority of original models were burned during demonstrations. Shortly following the revolution, circa 2155- young people who had known the anato-pig in it’s original inception, when they were school children began brandishing it’s form on trendy nick-knacks. The irony guiding this trend was not understood by the older generation, conservative outliers and the more extremist youth liberal parties. Critics of the fashion statement often categorized it’s followers as champagne-moderates with more mind for style than politics who had merely appropriated the anato-pig in the vain pursuit of an edgy new statement. Spearheaders of the trend deflected these accusations saying that the irony, meaning and theoretical underpinnings behind their statement were beyond the intellectual capacities of the critics. By the early 2160’s the anato-pig could be found ironically placed on posters in recent college grad’s apartments, refrigerator magnets, and baseball caps. In this era Anato-pig’s were often displayed in a dead-pan manner with little adjustment from their original forms, though certain fashion sub-groups preferred images of them that more directly expressed the satire-following this trend they were often presented in quasi-religious or violent configurations.

Reproduced with the permission of Noah Coburn.

Featured image: Amanullah Mojadidi. What Histories Lay Beneath our Feet? 2012. Kochi-Muziris Biennale.