When I teach undergraduates about ageing in anthropology, I sometimes begin by stating the very mundane fact that none of us are ever going to be as young as we are right now at this very moment. It is an obvious statement, sure, but also one that merits a dramatic pause. Some students give me a half grin, as if in on the joke, but others look a little worried or confused, waiting for the punchline. There we are, going about our daily tasks, then all of a sudden, we are placed within a stream of time that is perpetually slipping away from our grasp, moment by moment. Each moment we are just a little bit older (dramatic pause) but does being older mean that we are any different than we were a moment ago? When does a difference in quantity start to yield a difference in the quality or form of life we inhabit?

Age appears as something we are constantly living within, and yet something only available in retrospect, and only ever partially.

The more conventional way of experiencing age is, perhaps, through comparisons to others or through reflections about how others view us. Even when measured in years and months, age only really makes sense if we are younger or older than someone else and others see us as older or younger than they. Age, in other words, is a way of experiencing and embodying temporality as relationality. The categories of age (i.e. child, adolescent, adult, elder) are not prescribed categories based on clear biological transitions so much as achieved categories that are navigated and negotiated with the help of others. Anthropologist have depicted these categories as historically and culturally situated, and yet for those accustomed to their culture, the contingency of age is easily forgotten. Like kinship (that other way of living time through relationality), age is easily naturalized as a universal psychological and biological phenomenon. What could be more natural than growing up and growing old?

But as the world’s population ages through a combination of historically unprecedented longevity and low fertility, anthropology has slowly started to pay closer attention to how experiences of ageing are shaped by culture in ways that go beyond the tidy sequence of rites of passage or the structures of a normative generational life cycle. As communities age, new forms of historicity, meaning-making, value, imagination, and knowledge become foregrounded (Fischer 2015; Kaufman and Morgan 2005; Livingstone 2001). These lend themselves to alternative narratives of the well-being, dependence, and ethics (Cohen 1998; Lamb 2000; Taylor 2008). These narratives encompass not only the older individual, but also the family and caregivers that support them or abandon them, and in doing so, reflect on and reconsider their own possible pasts and futures (Danely 2014; Kleinman 2009; Parish 2008).

Marc Augé’s Everyone Dies Young explores these points, using them to reflect on himself, his cat, and the rest of us who are ageing in this world. For Augé, age is seductive in its promises of knowability and narrativity, and therefore to our own being. But Augé does not stop there. As Carrie Ryan points out in her review, such knowability undercuts the very contingency and unfinishedness of lived experience and prevents a conscious and powerful possibility to live otherwise. Auge’s reflections open up the possibility for age as both a ‘project of the self’ (Giddens 1991) and a political project of agency, reflection and resistance. Ryan thinks about Augé’s critique of age in the context of her own fieldwork with men and women living with dementia. Age in this context was experienced as nonsequential, fragmented, and paradoxical (though no less vital or meaningful). Ryan’s ethnographic instincts show how anthropology contributes by questioning whether deviance from dominant modes of ageing fits Augé’s view of resistance and agency (or if it needs to).

Jolanda Lindenberg’s post offers another ethnographic case study that challenges the capacity for agency or projects of the self/temporality when age is linked to illness. She describes how the search for meaning, for some natural anchor to the body’s vulnerability, is complicated as age-related expectations and assumptions are reassessed. Ageing, then, becomes a matter that is characterized by both fortune and misfortune, insecurity punctuated by moments of security. Again, age’s unknowability means that these fluctuations are never easily resolved, but instead, animate networks of activity and ventures into hope and mourning.

Casey Golomski’s post also takes up the political project of ageing and care, expanding the frame further by situating insecurity in old age within the historical and institutional frame of post-apartheid South Africa. His post begins with a policy document, released almost exactly one year ago, that in many ways transforms the health and social care challenge of an ageing society into a moral agenda of ‘justice, fairness and social solidarity’ by protecting resources from the pull of the market. Current realities, however, seem to indicate that this document and its related policy strategies have not yet delivered the vision of old age that was promised. As people age they must still rely on unpaid care and the leveraging of obligation, responsibility and good will to brighten up their Christmas.

My own post examines the ways Japanese policies aimed at increasing family care support are related to media representations of increased male involvement in care. Megan Mylan’s short film Taller than Trees might be considered one example of the way gender and labor are being reconsidered through the media. The film captures a day in the life of one man who appears to have not only adapted to the unrelenting tasks involved in taking after his frail mother, but also found in this experience ways of forging a deeper mutuality with his ancestors and others. The film works, I argue, because it relies on an audience who, like Japanese policy makers, assumed that men were less capable of caring than women. As this assumption is challenged in popular discourse, they may lead to policies benefitting women as well and to greater gender parity rather than inequality in its rapidly ageing society.

For the Indian transnational families in Tanja Ahlin’s post, caring responsibility in an age of global migration has created a space for mediating technologies such as mobile phones. Ahlin’s ‘bottom-up’ ethnography shows, how these technologies have become part of the everyday experience of caring, facilitating not only direct monitoring of older family members, but also the organization of ‘care collectives’ in both India and abroad. For older parents who relied on this technology to keep these collectives active, caring for their phone itself became an act of care for kin. As more older adults find meaningful connections with family through technology, they are also challenging assumptions about older people as passive care recipients, and migrant families as abandoning their parents.

As the posts in this thematic thread suggest, the anthropology of ageing remains strongly focused on care and dependence rather than on the many other aspects of older people’s lives (Buch 2015). This should hardly come as a surprise. Anthropologists have always been interested in the ways people care for each other and the ways these relationships find expression in social structures, symbols, and sentiments. And however active and independent one is in old age, no one is unaffected by these issues of dependence and care.

Population ageing has added a new urgency to the need for more ethnographic research on the connections between cultural change and an increasingly diverse range of ageing trajectories.

While care of older people is of critical public relevance to an ageing planet, so is the empowerment of older people by recognizing their life’s works and protecting their rights and dignity. Although a UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is entering its 27th year, there is still no comparable Convention on the Rights of Older People. Anthropologists working on care and ageing not only provide valuable empirical contributions to this sort of project, but also, as this thread illustrates, raise substantial critiques.

But of course, policy should not be treated as an end in itself. The excess of age is a site of political, cultural, and ethical projects, a place-time from which relations of care or violence become possible, an embodied experience of maturity that sometimes commands authority, and other times pity.

An ageing planet does not mean a dying planet, but rather one in which both young and old will have to rethink what those age categories mean and how they can work together to create new forms of social life.

I thank all of the authors and editors for their contributions to the thread, and all of the Allegra Laboratory readers.

REFERENCES

Buch, Elana D. 2015. “Anthropology of Aging and Care*.” Annual Review of Anthropology 44 (1): 277–93. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014254.

Cohen, Lawrence. 1998. No Aging in India: Alzheimer’s, the Bad Family, and Other Modern Things. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Danely, Jason. 2014. Aging and Loss: Mourning and Maturity in Contemporary Japan. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Fischer, Michael MJ. 2015. “Ethnography for Aging Societies: Dignity, Cultural Genres, and Singapore’s Imagined Futures.” American Ethnologist 42 (2): 207–229.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kaufman, Sharon R. 1987. The Ageless Self: Sources of Meaning in Late Life. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press.

Kaufman, Sharon R., and Lynn M. Morgan. 2005. “The Anthropology of the Beginnings and Ends of Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (1): 317–41. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120452.

Kleinman, Arthur. 2009. “Caregiving: The Odyssey of Becoming More Human.” The Lancet 373 (9660): 292–293.

Lamb, Sarah. 2000. White Saris and Sweet Mangoes Aging, Gender, and Body in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Livingston, Julie. 2001. “Long ago we were still walking when we died”: Disability, Aging, and the Moral Imagination of Southeastern Botswana c. 1930-1999. Dissertation, Emory University.

Parish, Steven M. 2008. Subjectivity and Suffering in American Culture: Possible Selves. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, Janelle S. 2008. “On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 22 (4): 313–335.

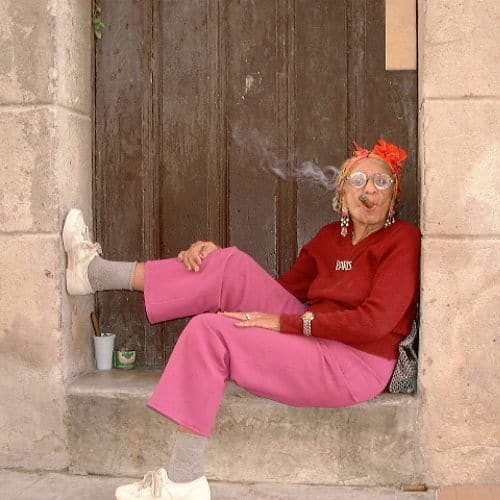

Featured image (cropped) by Jennifer (flickr, CC BY 2.0)