Over the last years academics from different disciplines have become increasingly visible on popular and social media, narrating personal stories and reflecting on the growing casualization of academic labour. Scholars have detailed the pressure of self-exploitation, impoverishment and insecurity, restless hypermobility, the instrumentalization of scholarship, indebtedness of university graduates at the benefit of ever richer high-ranking administrative cadres, and increasing movement of academics who quit the academy. Anthropologists Sarah Kendzior and David Berliner, among others, have also turned their attention to this subject. Kendzior has spoken for a generation of young scholars entering the market with minimum income but under maximum pressure for visibility. She narrated her experiences from conferences where recruitment and networking take place, and to which they have to pay their own way.

Becoming dependent on their own resources, mostly those who come from privileged families can keep playing the academic game. Berliner has expressed the anxiety of senior academics, who realize they have contributed to overproduction and competition within the discipline, often at the detriment of the discipline itself, but also against their own health and well being. In an informal discussion among colleagues from different generations of the latter article, further concerns have been raised. The bureaucratization of the application, recruitment, and self-evaluation, the brutal competition for short-term funding, the excruciating income inequality between an ever smaller cohort of star academics and an ever growing reserve army of adjunct faculty, have all been soared by the irresponsible increase of a number of PhDs within a shrinking job market.

Against this background, a whole generation of junior academics is exposed to an ever growing casualization of labour. In Ireland the preliminary results of an online study done by the voluntary efforts of precarious academics from the group Third Level Workplace Watch, have shown rather alarming results. In this country, which also happens to be one of the most expensive places in Europe, casual academics win on average 10 000 € annual income for an average of at least five years after finishing their PhD. In this “race to the bottom” in over 63% of the cases this income is generated by hourly paid work, done in 62% of the cases by women. Beyond national trends, a growing “internationalization” (i.e. transnational flexibilization) of academic work makes it a difficult subject of both research and organized resistance.

To stay in the academic game after finishing a PhD, in an English language research institution, one is usually required to put up with flexibility and recurrent migration.

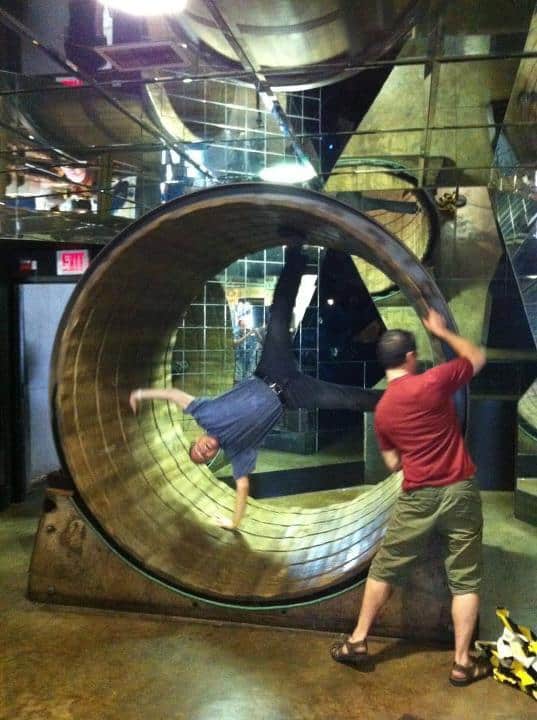

Those who get to do a post-doc or get a full-time fixed-contract teaching position are usually pressed to find time out of work in order to turn their PhD into publications. The shorter the time of the contract, the higher the probability that they return unprepared to the ever more competitive job-market and fall into what TLWW has called the hamster wheel of academic precarity once their appointment is over.

On the road of celebrated “internationalization” many are pressed to curtail their previous social and professional networks, and change countries every few months or years, if lucky. Many suffer loneliness and depression while others have to take on the responsibility of moving their whole families along or commuting across national borders to make ends meet. The others, who – out of choice, or often out of necessity – opt out of the game of transnational mobility, fall easily in the trap of zero-hour teaching and precarious research arrangements in order to stay afloat. Both groups are dependent on local or international clan-like arrangements of loyalty and hierarchy. In both cases individualized contractual arrangements and access to benefits and resources encourages cruel competition, often among colleagues and friends, and thus – ultimately – breaks all possible forms of solidarity among those affected.

On the road of celebrated “internationalization” many are pressed to curtail their previous social and professional networks, and change countries every few months or years, if lucky. Many suffer loneliness and depression while others have to take on the responsibility of moving their whole families along or commuting across national borders to make ends meet. The others, who – out of choice, or often out of necessity – opt out of the game of transnational mobility, fall easily in the trap of zero-hour teaching and precarious research arrangements in order to stay afloat. Both groups are dependent on local or international clan-like arrangements of loyalty and hierarchy. In both cases individualized contractual arrangements and access to benefits and resources encourages cruel competition, often among colleagues and friends, and thus – ultimately – breaks all possible forms of solidarity among those affected.

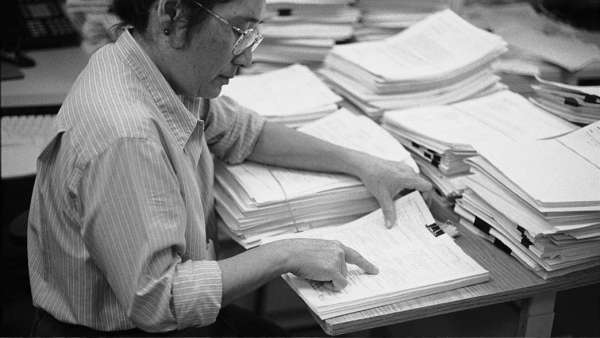

Women are particularly exposed to vulnerability with less access to permanent positions, and more emotional labor and care-giving functions both in and out of the academy. While those who have children feel losing the academic game because of the domestic burden of care in ever decreasing welfare conditions, those who do not have children feel deprived of private life due to growing imperative to do replacement teaching and administrative work. While university administrations outnumber academic faculty, academics do ever-growing amount of administrative work of (self-) evaluation to fit ranking-driven demands of the ‘global knowledge economy’.

And, while higher education has been turned into a profitable business in which mostly state funds are invested, it does not pay back into the state exchequer. It benefits industries, commercial publishers, marketing consultancies, retail and service providers, the profit is accumulated by growing exploitation of increasingly impoverished staff in the higher education sector.

Against this background, the recent debate that started on the Anthropology Matters list around the advertisement of Oxford’s Centre for Migration, Policy, and Society (COMPAS) for “casual researchers”, hit a painful chord. For many of us it pushed a further precedent of both contractual arrangements and of language that normalizes the precarious situation of many scholars. On the one hand, it seemingly offered a neat short-term research opportunity with payment that would allow a trained researcher to earn over a period of three months what one could gain for a year of full-time academic work. It also did not sound particularly exclusive or demanding in terms of credentials – one did not need to have a completed PhD or even an MA in a specific disciplinary field. On the other hand, the ad sounded more like a description of a job that could be done within a one- or two years’ contract, with benefits, as a part of an intellectual community, and as co-author of the final product of the project. The position also clearly required a specific profile. Put together, the requirements described a researcher at least at an advanced doctoral level, who has developed and could easily activate a vast network of up to sixty potential informants among “irregular migrants” from specific national and linguistic groups.

Conducting, transcribing, and encoding the interviews, which was to happen within the assigned period of three months, could have required a working week with an average of 20-hour work days. All of us familiar with the turgid process of entering or returning to an anthropological field, identifying interviewees, arranging, conducting, and transcribing interviews, could see how even with such workload, three months would not be sufficient to finish the work. So, the latter either had to continue beyond the given time, or the income was to be significantly reduced. The ad did not state any meaningful way in which the researcher could claim ownership of the data, findings, or any form of recognition on the published outputs of the project. It was clear that COMPAS – a research centre that takes pride in doing ground-breaking research on labour migration – was looking for a way to further boost its funding and publication portfolio by exploiting an academic labour migrant and, by proxy, a network of irregularized labour migrants.

The first public response to the ad posted on the mailing list of Anthropology Matters, was published online and widely spread. The ad provoked further responses – mostly by junior academics, often working under casual labour conditions. Many detailed on social media further stories of exploitation and attendant problems with their own health and wellbeing. The COMPAS director issued a vague piece of no- reply sent to all who protested against the position in private or in public. And while he assured all of the high ethical standards of COMPAS in caring for the wellbeing of their current and potential temporary contractual staff, the anger has not been quelled. Colleagues in the field have been organizing to look for ways to protect precarious anthropologists. While many bigger or smaller campaigns have already taken place locally – e.g. at different universities and by different groups in the UK, US, Italy, and Ireland.

The disparity between labour conditions, welfare provision, and the hierarchies in prestige and ‘value’ attributed to higher education in different countries is what still makes exploitation possible and makes hyperflexibility and hypermobility seem like a normal part of the deal.

A struggle can only be meaningful if it brings awareness of the shared interests of people across borders and across professional divides: students, university service staff, and academics with different positions need to realize the shared interest of doing away with the exploitative system at place. And while it may come from those who stand at the lowest of the ladder and fall further into poverty and invisibility, this fight has to be an organized struggle with methods that are not only pleasing but that of which challenge and disrupt complacency. We all need to make an effort to monitor working conditions, and put pressure on funding agencies, university administrations, research and teaching institutions, and individual gate-keeping academics. We all need to discuss possible ways to make the redistribution of funding and working conditions more fair.

The betterment of working conditions is needed to end the growing anxieties and leave us time and space for our teaching and research, as well as for the pending debate of how to reform the university, make it more democratic, more open, and attuned to the needs of society as a whole. In an era when labour unions mostly stand behind those in permanent employment, or fight precarious labour conditions in court on an individual basis, we should come up with new forms of mobilization across borders.

The betterment of working conditions is needed to end the growing anxieties and leave us time and space for our teaching and research, as well as for the pending debate of how to reform the university, make it more democratic, more open, and attuned to the needs of society as a whole. In an era when labour unions mostly stand behind those in permanent employment, or fight precarious labour conditions in court on an individual basis, we should come up with new forms of mobilization across borders.

Over the last days, colleagues have suggested unionizing, petitioning, picketing at conferences, boycotting their academic production, international strikes, and participating in action days. However, we should also not forget this fight can and should not only happen for the benefit of our own profession. Being in the academy has often been a privilege that has allowed the majority of us, even when we have researched marginalized groups’ plight for survival and dignity, to stay far removed from these political struggles. The casualization of academic labour, if painful, is a good lesson to remind us that while a system creating extreme inequalities persists, no one is immune from the race to the bottom.

*) The ‘neoliberal race to the bottom’ is a phrase used to describe academic precarity, which is used by the collective of Third Level Workplace Watch in the preliminary analysis of their ongoing online survey.

Featured image by NASA HQ PHOTO (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Thank you for this thought provoking piece of writing that stated the gruesome facts of the conditions we face as researchers. Having for long been an involuntary member of the academic precariat I am in an ambiguous way pleased to see this discussion has finally gained momentum. I am ambigous because I naturally wish we would not have to fight for these rights that are obvious workers rights regardless of profession. I live in a country, Finland, where a very large percentage of the workforce is unionised and at least in my generation it has been clear that you pay a union membership to have representatives defend your rights. The union I belong to does good work and, undoubtedly, I could be more actively involved in their work. In addition there should be campaigning, active protest and visible actions – a definite activist stance to defending the knowledge industry that we represent. To stay afloat in the game of academics and also be a parent and a daughter to aging parents I, not only lack job security, but also TIME to be politically engaged. This a good strategy to ensure the silencing of protest; keep us so busy with the basics of life that we cannot spend time on defending our own welfare. In the neoliberalising world order of short-term thinking and a race for profits, there seems to be little concern for the intellectual property rights of academics or the production of knowledge that we are involved in (or we can have these rights if we pay for them – in what other profession does one pay to have one’s own work published, to have visibility of one’s work and to spread knowledge of research that benefits society?). There seems to be a move towards claims that what we produce as academics is not productive because it cannot be measured in the short-term. In a market-based manner of thinking the investor feels he has the right to ask what the (short-term) returns on his investment are. It is so true that precisely at this hour we need solidarity between researchers so as to fight as a unified front against these threats to the academic profession. Every time a new change takes place (like a few years ago researchers on grants were told they had to pay for their office space, sums that were about 10% of their monthly earnings) that indicates the onslaught of market-based thinking in a (still) state funded university system we write angry emails of indignation and organise some protests. The problem is that this action is not militant enough and does not trickle up to the decision makers – there is a wall of university administration and decision makers that barrikade our path to making ourselves heard, and in all of us lives the fear of labelling ourselves trouble makers, of black listing ourselves. What classical means do we have to protest? Going on strike? This works if all university staff go on strike so that teaching, exams and tutoring stops. Refusing to write articles in academic journals will just be a disfavour to us when we need to get more funding. A cross-border, transnational campaign to save the academic profession is an effort I would gladly support – there is strength in numbers! Count me in and lert me know what I can do to further the cause.

Hi Susanne, thanks for your response! I can’t agree more with the points you raise. And it is so difficult to gather and act in a meaningful way as we’re so spread out, and hypermobile, moving between contexts with different labor relations and conditions all the time… But let’s hope we organize at some point and find a way to get back our voice and visibility… In solidarity, Mariya