The Anthropology 4 Kids book “What is a nation?” begins like this:

This book is a game. We are going to invent a new nation together and, at the same time, we will think why in different countries and at different times people have thought so differently about what [a?] “nation” is?

After all, isn’t this what anthropology promises us, demonstrating how people in different countries and times can live in radically different ways while remaining humans?

During the workshop in Iceland in 2019, it was fascinating to observe how children encountered various social possibilities as they moved from page to page, and even more importantly, as they encountered lots of free space for them to draw, write, and invent their own ways to interact with the book. As a result, by the end of the workshop, each participant had effectively created their own book, with their own version of what a “nation” (“country”) might be.

And here’s the thing to notice: often we write diaries and read books alone. But a nation, a country, a community is necessarily a collective project. How can we actually imagine such a thing collectively? Here we cannot limit ourselves to a book—this is only the starting point. So after distributing the books, the next step was to introduce the Tablecloths as the focus for what we called ‘Visual Assemblies’.

After all, isn’t this what anthropology promises us, demonstrating how people in different countries and times can live in radically different ways while remain human?

Here’s how it worked. First, we prepared city plans in advance on large (2×2 meters) sheets of paper. The plans were intentionally unfinished. As with the books, there was plenty of space for kids to draw and write. Next, the tablecloths were spread on tables. The children would gather around, and Kolbeinn Hugi and I acted as mediators for the improvised Visual Assembly, in which participants had to agree on how they would live together in a newly invented imaginary city/country/community, and in doing so, filling in the empty spaces with a magic marker.

It was a challenge for these modern schoolchildren, who rarely work together, are often pushed to compete with each other for better grades and seldom have the opportunity to exercise their own free will even individually, let alone collectively during school hours.

We were continually being asked: “Can we really draw whatever we want?”, “What kind of laws are we allowed to pass?” ,”Do we need to ask you if what we’re doing is ok?”. Their teachers, hovering nearby, seemed to reinforce the impression that kids should not be allowed to implement their own imagination without obtaining approval, for fear of failure. Instead we answered:

“What kind of laws would they be if you had to ask permission to make them? You can invent whatever laws you want!”

“We aren’t your bosses. All we do is hand out pencils and help to arrange the tablecloths for you.”

“We are not here to control and check, just to help and support.”

Many participants were genuinely shocked. We had to devote a considerable amount of the time allotted for our workshops to un-schooling them. We first had to ensure the kids truly believed us when we reassured them that we genuinely were interested in learning what they thought and weren’t using the exercise as a trick to test them in some way.

Here it is worth applauding the talent and skills of Kolbeinn Hugi, who used his professional experience as a rock band member to coordinate more than a hundred children. Let me describe how one of the sessions proceeded.

The ambitious goal of A4kids is to create a space for experimentation in which it is possible to seriously discuss issues to which no one has the final answers.

Imagine dozens of tables in a huge hall, with 12-15 children sitting at each. They draw, write, invent, and therefore negotiate with each other, squabble, and make up. They need to decide among themselves what to put in their city center: a shopping district, a government building, a giant playground, a rocket launch pad or a huge prison? How will the people of this new world live together: will they be divided into poor and rich? Will they have bosses? How will they treat visitors, the elderly, and what rights would children have in their world?

The children wrote down their laws on small cards, and after negotiating among themselves, drew and changed the plan of their city on the tablecloth. At one of the tables, boys and girls split into two hostile camps. The boys voted for laws that deprived the girls of all rights. The girls immediately built a wall separating the city into female and male districts, where in the female territory boys would have no rights either. Girls passed a law that required boys to give birth to all children.

In the women’s part of the city the girls initiated an indefinite protest (all of this was colorfully depicted in their plan).

On another Tablecloth, the whole city was overgrown with flowers, and wild animals roamed among them. There were cities where shopping malls occupied all the free space, and there was a society where people’s main occupation was sport.

Lastly, we – the mediators – who did not intervene in the creation of city plans, arranged a new game: every twenty minutes, we asked the participants to swap tables with their neighbors, rewriting their laws and redrawing their plans.

For children who had gone to the same school all their life and lived in a small Icelandic village of 50 people (for this workshop we brought children from many villages and towns by special buses), this was a veritably anthropological experience; they divided themselves into tribes, then confronted each other’s newly created cultures as outsiders.

The ambitious goal of A4kids is to create a space for experimentation in which it is possible to seriously discuss issues to which no one has the final answers. However, we know sincere discussions are only possible in the space of freedom and that freedom often starts with play.

I started the game with myself, before going to Iceland, by remembering my own childhood in Leningrad in the late 80s.

I grew up in a dormitory suburb of Soviet Leningrad (5 000 000 people) in a house where some 5000 people lived in 1000 apartments. The population of our district Moskovsky (350,000 people) is comparable to that of Iceland (360,000 people). We dreamed of going to the city center on weekends, going to museums, theatres or parks. But why did we, as residents of the Moskovsky district, aspire to study and work in the ‘center’? Why didn’t we dream of building our own Museum of Modern Art to contain the artwork of our neighbors and friends, a museum of national pride in the Moskovsky district, a Moskovsky district parliament and park, and send our own ambassadors around the world? Why didn’t we organize to discuss our own local constitution and choose our own president and parliament (or maybe invent some other political forms of co-existing with each other)? Why did it never occur to us?

Why didn’t we dream of building our own Museum of Modern Art to contain the artwork of our neighbors and friends?

These are the questions that originally inspired the doodle book What is a Nation? that we used as the primary text in these exercises. As in all the books in the A4kids series, it tries to balance the fine line between the very personal experiences of participants and academic discourse. What is a Nation? is based on interviews with Keith Hart, David Graeber, and other anthropologists. But it’s also meant to draw scholarly topics of debate out to the public. These cornerstone subjects are often monopolised for debate by elitist universities and museums, and not easily accessible to the general public – let alone schoolchildren. Our project’s goal is to bridge this gap through art and play, making connections that allow us artists, academics, parents, adults, and children, to collectively ask the questions which none of us can answer alone.

In a way, Anthropology for Kids is indirectly inspired by Alexander Bogdanov’s project Proletkult, which existed in the early years of the Soviet Union. Bogdanov invented and managed to implement a fairly large and complex infrastructural project. Grounded in the completely new and revolutionary principle that each person is an artist, and communism is not only the public control of means of production – communism is also a society which can radically transform the boundaries between production and consumption, creator and consumer, teacher and student.

Long before the creation of Wikipedia, Bogdanov and his comrades imagined and began to create a new infrastructure for the reproduction of knowledge, one that would destroy the traditional hierarchies between “students” and “teachers”, and supplant them with horizontal networks in which anyone could find themselves in each role in different situation: readers become writers, spectators become artists.

Long before the creation of Wikipedia, Bogdanov and his comrades imagined and began to create a new infrastructure for the reproduction of knowledge.

Alexander Bogdanov aspired to build a new type of cultural relations. And despite his quick removal, the years of authoritarianism that ensued in the USSR, and the subsequent destruction and privatization after Perestroika in the 90s in those countries – remarkably much of this infrastructure is still in place. It was so well-designed and effective that it remains as permanent as a well-constructed building or well-planned neighborhood.

Having lived in East Berlin for a long time, I know that not much has changed: children can have music and art classes there almost free of charge, while kindergartens stay open until late at night. In St. Petersburg, in the heart of the city one can find a magnificent palace, the Palace of Pioneers. Its doors are still open to every child who wants to learn anything from a vast variety of subjects from science to art.

Bogdanov’s ideas – like a well-written computer code- turned out to be so tightly sewn into the social body that it is almost impossible to uproot them.

In every district of the city, there are houses of culture, where children (from all social strata) can come – for symbolic payment or free of charge – to practice aikido, music, ballet, puppet theater, chess or the Chinese game Go. After the October Revolution all over the territory of the USSR, completely new but very sustainable behavioral practices were created (and in many ways, we have to thank Bogdanov for this) which made childhood and education an integral part of the adult world in a very specific way.

The main responsibility of adults was not to censor the surrounding world, preserve children’s naiveté or provide financial support, but rather, first and foremost, to allow access to numerous, diverse and developed cultural and creative practices which every child was entitled to.

Everything was privatized in Russia during Perestroika, but to privatize the premises of children’s enlightenment, one would need to break the spell cast by the Russian Revolution – a spell no one in their right mind would dare to break.

Similarly, Anthropology for Kids is designed to challenge the division between the production and consumption of knowledge. It may seem insanely ambitious, and perhaps it is – but I’d like to recreate some of the cultural habits born out of the early years of the revolution, and make these tools available to everyone willing to engage with them anew.

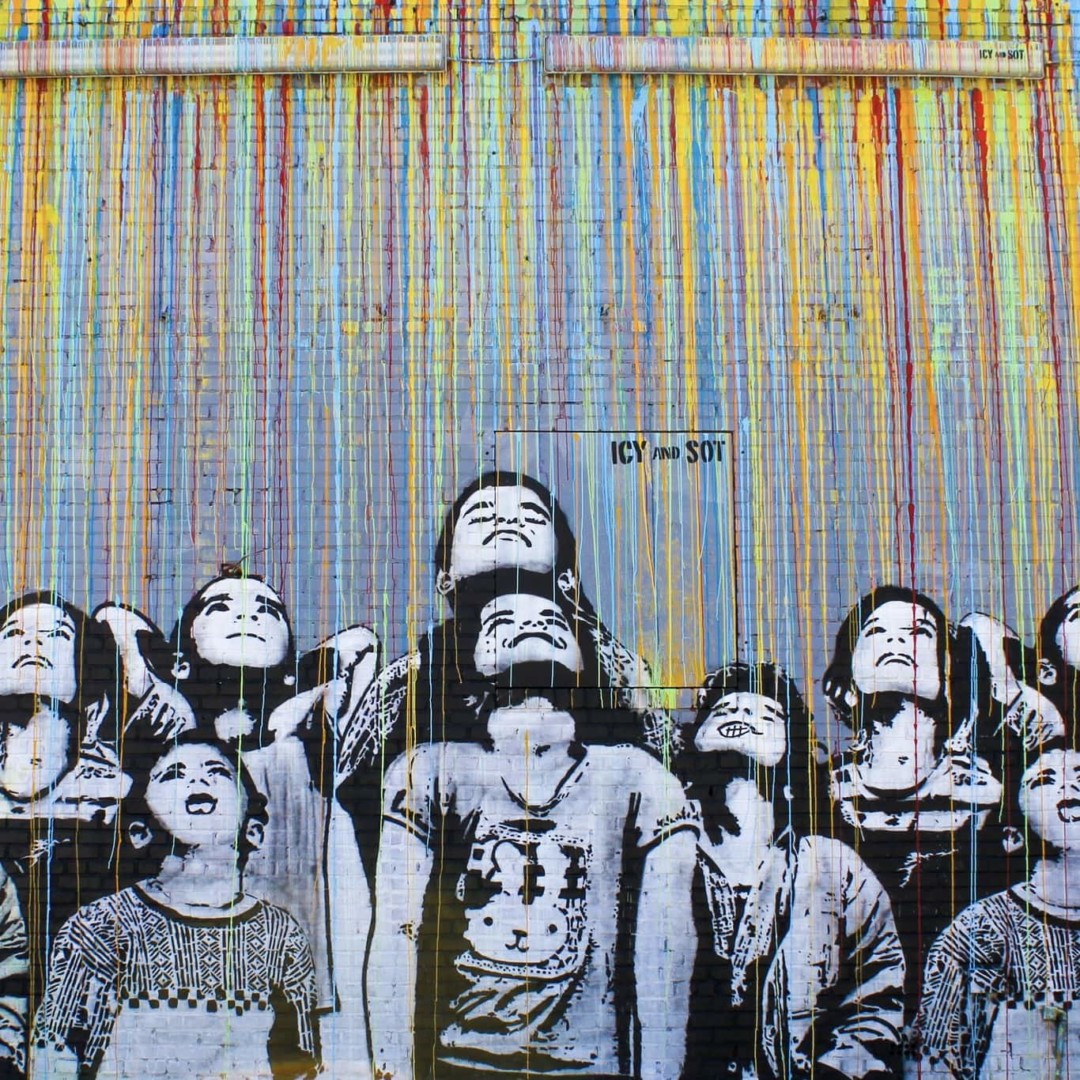

Featured photo by Leonardo Burgos on Unsplash.

All other images curtesy of Nika Dubrovsky.