This is the second part of the conversation our assistant editor Emilie Thévenoz had with Nika Dubrovsky (Read part 1 here). They chatted about some of the workshops Nika organised, and how children sometimes just need a framework through which to think the changes in their society, and the importance of fostering pushbacks. They also talked about how children, their parents and the institutions involved sometimes reacted to the A4Kids workshops.

******

ET: When I was looking through the material that you have online, I was really struck by the fact that it confronts children with the idea that there’s perhaps no universal objective truth out there, that there’s no right or wrong answer. I think this is a core lesson of anthropology. I come from a family with a lot of kids and teens, and I noticed that it’s something really hard for kids to grasp: we’re taught that there’s good and bad guys good and bad decisions, good and bad ideas, and also that there’s a scientific, objective, quantifiable truth out there. And so I was wondering, how did children respond to this sort of ambiguity or uncertainty?

ND: I don’t really like moral relativism. I do believe that there are right and wrong ideas, you know. I think it’s more about how you form what is right and wrong. It’s as you said – is there a quantifiable truth that just could be implanted? I think kids in general don’t accept the quantifiable truth that others try to implant in their heads. They resist as much as they can, but they are also trained that “resistance is futile ”. So every time I would do A4kids workshop, I would encounter a kind of mistrust that you have to overcome at the beginning. For example, I was doing a workshop in a London public School based on a book about “What is Privacy?”.

I think kids in general don’t accept the quantifiable truth that others try to implant in their heads.

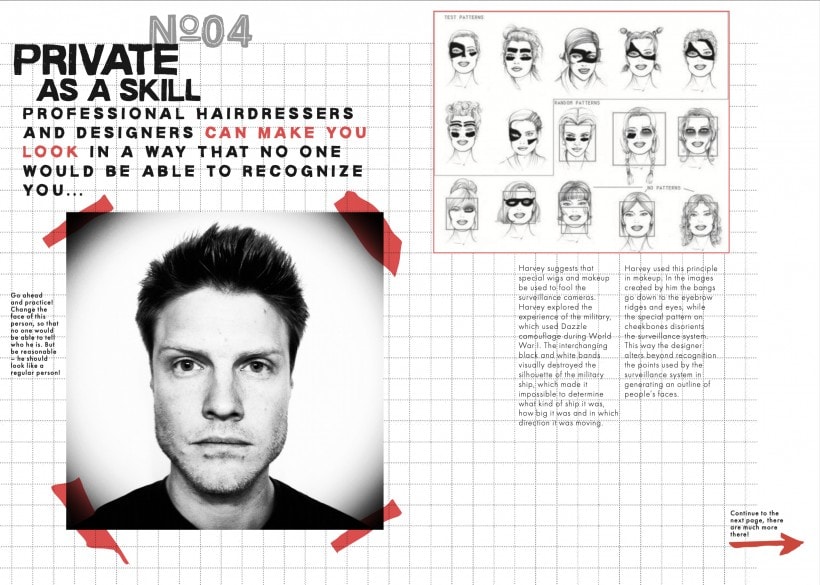

The London’s institution organized the workshop called the Showroom. It was based on the book “What is Privacy?”, a collection of notes about different ideas of what is public and what is private.

Since it was an art project initiated by the wonderful art collective from Zagreb WHW (for Whom What and How), there were many examples of the art from ex-Yugoslavia in the book.

So we came to the regular London public school full of working-class kids, mostly with a migrant background, to talk to them about privacy – although we knew that upon entering the school, the students have to give up all their privacy rights. These kids are practically adults, 16 and 17 year-olds. They have their own opinion and life experiences, but the school’s infrastructure and how students are treated there reminded me in some ways of a prison ward or of a psychiatric facility. There were security cameras in every corner of the school that recorded students‘ every move and gesture and a strict hierarchy was enforced between students and teachers.

So, it took a long time for us to gain their trust. But once we did, we had some very interesting conversations.

There were pretty radical examples in the Privacy book. Contemporary artists used their own nude bodies to show the vulnerability of the artist and the human being in general. It was interesting to see how the kids, who may never have seen contemporary art before, related to these artistic gestures.

There are funny examples in the book of how, just 100 years ago, American police officers went around to measure the length of women’s skirts to punish those whose skirts were too short. This really amused the students, for whom the United States has always been an example of freedom in every possible way.

There’s a story about Snowden in the book, who is being persecuted for telling the world about American surveillance on its own citizens. The children had a heated debate about whether citizens deserve Snowden’s sacrifice and how to protect him.

It is said that in some cultures, people don’t allow others to photograph them because they believe that someone is stealing their image along with the photograph. This page was a real success. It sparked a conversation about how today, you can take someone’s picture and Photoshop it to really “steal” the identity, with life-altering consequences for that person.

So I think society’s changing, and it would be strange if the children were not a part of that. Yeah, and they just need to find a framework through which they would be able to discuss it in public.

ET: This brings me to my next question. Your books often deconstruct or question notions that many societies, many groups of people hold very dear, such as power, money, the nation. And, you know, some people would say that these notions are maybe even the glue of the society that we live in. And so maybe your books are very unsettling for some of the students, right, like, suddenly a lot of things that they’ve been taught to hold as important truths are being deconstructed. Do you notice this effect? And have you had any pushback from teachers, parents, or even the children themselves?

ND: You know, my books are not mandatory. So if you don’t like them, or you don’t feel like they’re for you, don’t’ read it.

But of course, it’s presenting all points of view.

The books never say that one point of view is more valuable or more right than another. But yes, when we were doing an exhibition on the book ‘What is family’ in Moscow, Russian, in the country where the government had passed the law that punished if you distribute –specifically among children – any ‘non-traditional family values’, so, basically, a law directed against gay people. And of course, this book showed that humans arrange families in so many different ways: it could be one mother, one father and a couple of kids. It could be an extended family. It could be two mothers and kids, and it could be two fathers, so on so forth, you know, for example, Tibetan families often consisted of one mother who had several husbands. The husbands were brothers among themselves and raised all the children together. Yeah, so that exhibition was closed.

A4kids is an emancipatory and political project, so of course, it questions authority by challenging the conventional wisdom, which is often just an outdated belief system.

A lot of preconditioning is implanted by society – in Russia, it’s called skrepa (a brace), an old word that’s now used for propaganda of what it called “traditional values.” So in this sense, we have traditional skrepa which refers to the things that are holding us together, something that’s holding the community and country together. The Russian government is saying that what is holding us together, of course, is our Russian Orthodox religion, although there are many other religions, too; and it’s our family traditions, and so on so forth. And it’s the same in the US. Trump was a very good example of that type of values, like ‘the American values’. This is everywhere, but so is a counterculture. And anthropology itself, it’s in between.

But I think childhood is the right time; there’s much more resistance from adults, not the kids, because childhood is a time when we are still open.

A4kids is an emancipatory and political project, so of course, it questions authority by challenging the conventional wisdom, which is often just an outdated belief system. In this process, discord is really useful. After all, this is how any culture develops and lives, redefining itself through such terms as “us” and “them” and moving these borders.

ET: And the kids, they don’t push back against all the work that you’re doing?

ND: They can push back because there is space for them to push back. These are workbooks you know, and if it’s a workshop, it’s even easier to push back. The books pose questions. We had a workshop about the wealth book with homeless kids in Berlin. A boy was there who was originally from Russia, from Samara. And he was telling us how rich he and his family was there, and through his description, he was saying ‘everything is wrong in this book’ and ‘the richest place is Samarra’, with his wooden house and a big garden full of apples with his grandmother, who always invited him to eat and… and so on. He wrote so much about this, a truly poetic text. And I, you know, I, I cannot disagree with him. This is truly a description of happiness and richness…

Together with the teens from a homeless shelter, we asked questions and looked for answers, by sharing our very different life experiences.

The idea is to create values together, not impose values on each other.

The idea is to create values together, not impose values on each other.

ET: That’s also not something that children are used to. Normally, you know, especially in a school setting, they’re being taught, this is what you should know, this is the knowledge that we’re imparting upon you. So how do they react to this liberty, to this ability to think on their own?

ND: As I said, it’s very difficult in the beginning just to gain trust. And there are a lot of tricks on how to do that. For example, if you do the workshops, I can guarantee that one of the kids or a group of kids will be disruptive and distrustful; and that person or group will likely be the key for the whole project. They will often cause a confrontation, and this is what often sparks the debate.

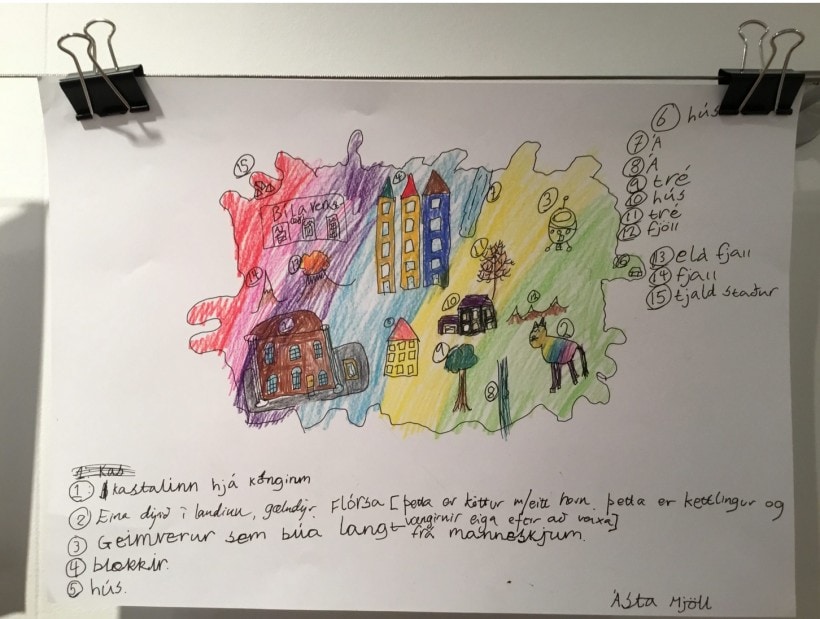

For instance, in Iceland, when Kolbeinn Hugi and I were doing the workshop based on the book, ‘What is a nation?’, we gave the kids a huge piece of paper to collectively draw an imaginary country.

The boys in a specific group decided that girls would have no rights in their imaginary country at all. The girls would obey the boys. So the girls got together to draw in one corner of this country what they called ‘the woman corner’. They said, “the women will not be giving birth to the kids anymore. So if you want to have a next generation, you have to figure out how to do it by yourself.” Then, the girls started to develop a plan for a feminist city, writing down numerous rules and then entering into negotiations with the boys.

Lots of kids from other groups surrounded this map to listen to their negotiations.

And the pictures turned out great, too!

So here, they were really testing the ground. They were asking, “Can we do really anything we want or not really?” And once they understood that they could, they just put what’s really going on out in the open. This was in Iceland, in a small town, mostly fisherman villages. I believe they live in this very tough community, maybe very patriarchal. Iceland also the first country in the world where a woman was elected prime minister and it has some strong feminist traditions. So I think society’s changing, and it would be strange if the children were not a part of that. Yeah, and they just need to find a framework through which they would be able to discuss it in public.

That’s what we provided for them.

ET: and what new projects are you working on at the moment?

ND: So now, this summer, we’ll do the project called Visual Assembly that is coming from part of the workshops of Anthropology for All (as we now call it). With David, we did this visual assembly in the first lockdown, which was about ‘city of care’.

Visual Assembly was born out of workshops based on the book ‘What is a Nation’, where children invented and drew in large groups a map of an imaginary country. David and I decided: we would like to be kids too! Let us grab some chalks, go to the main square, and come up with a map of the ‘City of Care.’ So we did exactly that with our friends from Extinction Rebellion – who joined via zoom.

Now we are continuing this project at the Museum of Care.

Next year on David’s Memorial Day, October 11, 2021, we plan to create a public art project with chalks on the idea of the Museum of Care in one of the squares of some big city.

There would be no colonial treasures in our museum, no guards, and the main value would be the human relationships themselves and what derives out of this: maybe dreams, maybe friendships, maybe discords?

But we also don’t know how it will turn out: a collective art project is always full of surprises.

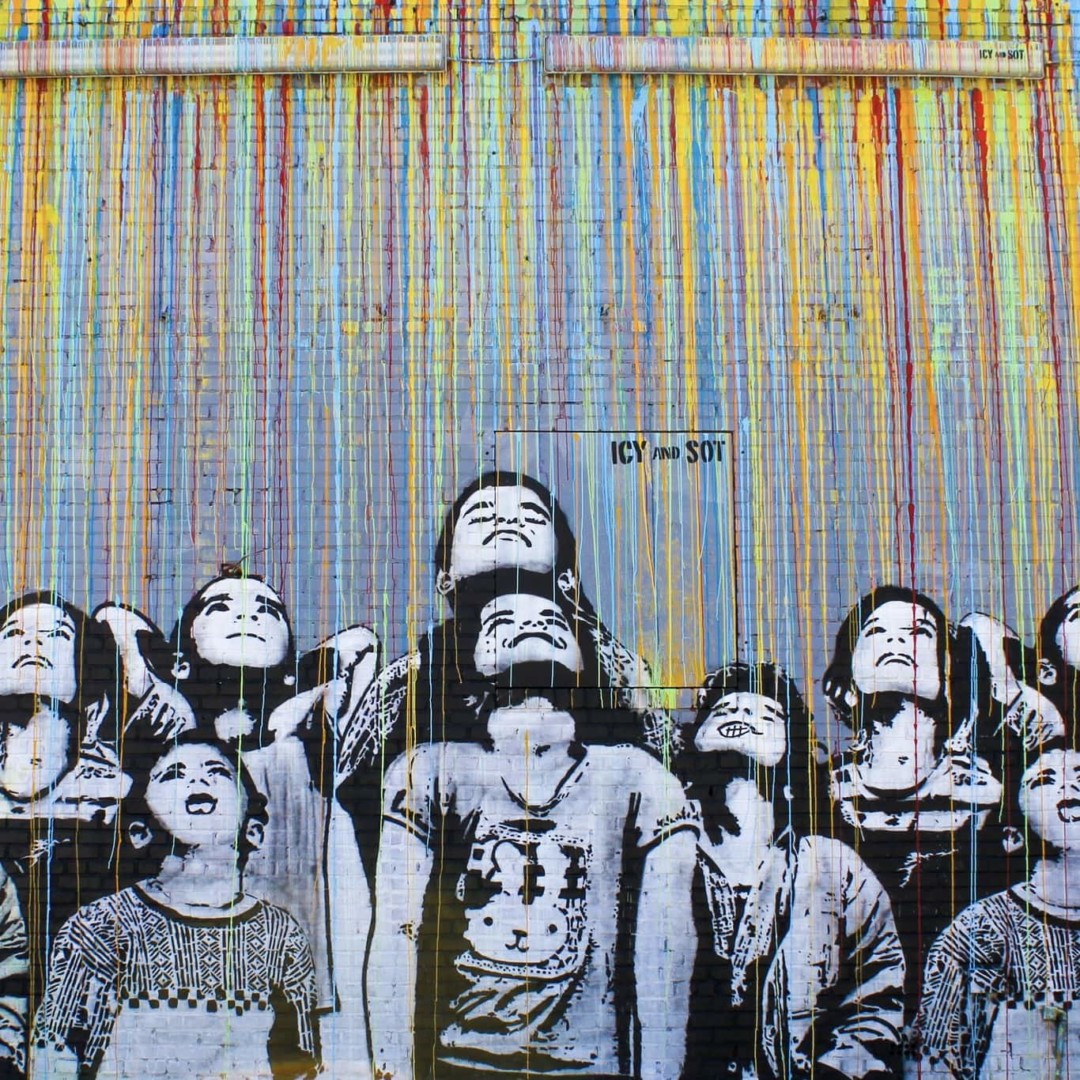

Featured photo by Leonardo Burgos on Unsplash.

All other images curtesy of Nika Dubrovsky.