“Anthropology for kids” as a research project

I spent most of my life doing two things – raising children and moving from country to country. I’m an eternal immigrant. England, where I live now, is my eighth relocation.

My husband, who is an anthropologist, once told me that he thinks that all immigrants are anthropologists. After all, our work is much the same as that of the anthropological fieldworker: to study an alien culture through immersion, to decode new cultural concepts, and learn new languages. But where fieldworkers try to gain knowledge for academic purposes, for immigrants the stakes are higher – they have to recreate a life in a new place. A failed adaptation can end tragically.

I’ve often heard it said that women adapt better in new situations, acquire working language skills and establish connections with unfamiliar environments faster than men. As a female migrant, I have observed how women’s practical approaches to adaptation are often more effective in achieving the desired results: coordinating with neighbors for help with children, learning local recipes or the dos and don’ts of shopping, rather than enrolling in formal education or entering employment in the new place of settlement.

All immigrants are anthropologists. We study an alien culture through immersion, decode new cultural concepts, and learn new languages.

Anthropology for Kids feels like a natural extension of what I have been doing all my life. Originally, it was born out of an attempt to find books for my 6-year-old son that would be accessible and clear in broaching the “grown-up” issues which truly interested him, such as power and servitude, death and immortality, beauty and ugliness.

Children’s literature in the West (at the time I was living in New York) is the most regimented and censored area in publishing. Children’s books are big sellers – along with toys – as they’re one of the last things consumers are willing to scrimp on. All kinds of authorities and censors, parents included, lay claim to this territory and try to shape it: from the book’s contents, to the size of the font. Not only is children’s literature supposed to be radically different from so-called adult literature, allegedly “age-appropriate” markers further compartmentalize the category. This mirrors the current schooling system, which separates kids by age (and sometimes by gender still now). What is appropriate for children in the “5-8” age group, according to these regulations, would not interest those from eight to twelve years of age. The content is also of course scrutinized: moral conformity, political correctness, and all that fake etiquette I remember so well from late Soviet times. Who now remembers the tons of children’s books describing happy collective farmers and small boys dreaming of joining the police force, which were published in the time of my childhood?

In every culture, in one form or another, any significant texts had to once break through the shadow of conformism. Sometimes breakthroughs come from revolutions in the literal sense of the word, as was the case in the Soviet Union, where the October Revolution led to the emergence of brilliant children’s literature – which was later unfortunately quelled by the conservative counter-revolutionary Stalinist cultural policy.

Children’s literature in the West is the most regimented and censored area in publishing.

Often, breakthroughs arise from going beyond the canon and reaching out to practices from the margins: folklore, absurdity, and various forms of buffoonery. The first edition of The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss was withdrawn from libraries across the USA for its inappropriate content. Many American readers were unsettled by the presence of strange Freudian Things: One and Two, and the irresponsible mother who went away leaving the poor children and fish, was also simply outrageous. Another icon of American children’s literature, Maurice Sendak, met a similar fate. The surrealistic hero of his first book In the Night Kitchen, the three-year-old Mickey, is shown naked in some illustrations. In some states, librarians concerned with the moral integrity of their young readers glued paper panties to the relevant pages to cover Mickey’s shameful nudity, while others demanded the book be removed. Sendak himself spent his life concealing his homosexuality.

Today, the world’s ruling powers have largely come to a consensus that childhood must somehow be protected from potential harm. what this means in practice is unclear – we adults haven’t even yet come to an agreement on what exactly defines a “child”. In modern Germany, for example, anyone under the age of 26 is considered a child in one way or another. If, for example, a young person is engaged in university studies, both their parents and the state are obliged to provide him or her with a minimum maintenance stipend and health insurance. If the parents refuse to pay, their child has the right to take them to court.

In modern Russia on the other hand, compulsory education ends at the age of fourteen and all family obligations towards the child are terminated, hence demarcating the end of childhood. A fourteen-year-old in Russia bears criminal liability and could end up behind bars (as well as in the USA).

We can’t be certain what a child is, nor can we say with assurance what an adult is or what a human being is.

Kids are, in a way, the radical Others that we compare ourselves to as adults. (…) They are our yet unrealized Utopia.

Kids are, in a way, the radical Others that we compare ourselves to as adults. Children embody the very possibility of another world and another future for all of us – a future in which almost anything is possible: a world of peace, flying cars, interstellar travel and a long, happy life for everybody – that is, if only they manage to accomplish it when they grow up.

Children are our yet unrealized Utopia.

Here’s the paradox: on the one hand, children need to be protected as bearers of hope for a better future; but often this well-meaning “care” results in them being stifled. They are ascribed a (quite imaginary) angelic naivety, bordering on stupidity, which results in reams of children’s books full of fluffy puppies and squirrels – a façade of political correctness.

At the same time, this concern and aspiration for a better future is realized through a contrasting approach: urging them to look at the world realistically, not through rose-tinted glasses, and to be prepared to accept the rules of the game, wherever they might end up.

Having recently gone through quarantine, we could draw an analogy between education and vaccination. During the recent lockdown, many countries imposed penalties for quarantine violations, while others launched public relief and education programs for all residents, emphasizing that we are all one big social body and equally dependent on each other.

But let’s imagine for a moment what would happen if vaccines were available only to those that could afford them… So long as a certain percentage of the population remains unvaccinated, we’ll never be rid of the virus for good. We would never have gotten rid of smallpox, leprosy, and plague if most people hadn’t been duly vaccinated. And whereas we can all agree how disastrous the effects can be in terms of health, this very different when it comes to education. We understand it as entailing the task to shield “children” from things they are somehow not ready for.

Some children study philosophy and liberal arts, while others only have arithmetic and writing. It is clear that poorer children are at a disadvantage: in most of the countries of the world, there are no philosophy and anthropology, music and algebra for them. But this is accepted as the status quo, even if that divide continually reproduces a violent and sick society. In the end, even the privileged beneficiaries of a precious and diverse education will suffer, too, because they will have to live in a world that is unfair, ugly and inhumane. Education is an expression of the human desire to understand the world, but it also shapes the society we are trying to understand.

Education is an expression of the human desire to understand the world, but it also shapes the society we are trying to understand.

My son was born in the USA, but his first language was my mother tongue – Russian. Only slowly did I realize that all my efforts to share a language (and culture) with him would be wasted, since the Russian language itself has been changing so much while I’ve been living abroad.

Russian children’s literature during the years of neoliberal reforms that followed Perestroika, were dominated by commercial publishers disseminating tasteless Disney-style forgeries. My first real encounter with colonialism was when I lived in the Dominican Republic for a year, where shocking poverty is combined with corruption and the domination of Western corporations in all areas of life.

When I went into to a children’s bookshop in Santo Domingo, I understood the real meaning of “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (by Gavatri Spivak). Although the Dominican Republic has its own vibrant cultural traditions, a culture of social resistance and the interweaves several national cultures, there, on the bookshelves, I found only Disney books about Mickey Mouse and Snow White, badly translated into surrogate Spanish. The souvenir vomit from the American mass-market filled the bookshelves like the terrible substance from Ridley Scott’s Alien filled the bodies of humans that the aliens attacked. I was horrified! How will Dominican kids learn Spanish from these books?

Later I learned that in schools, Dominican kids are told that Christopher Columbus brought “real culture” to the island, and so forth…

Living in an expat paradise – the Dominican Republic – I understood how complex colonialism is, how it destroys us from within. And how it begins with cultural appropriation, which nowadays manifests itself to a large extent in children’s literature.

After Perestroyka, Russia, and most post-Soviet countries, were in a similar situation, and, naturally, I wanted to change it.

I spent quite some time and energy on publishing Dr. Seuss’ books in Russian. I don’t know how much this publishing project influenced the shape of contemporary Russian culture, but I tried to do what I could to nudge it in a more Dr. Seussian direction. In fact, at the same time, many young Russian-speaking moms, many of whom, like me, had lived abroad, started to organize small children’s publishing houses, creating a real publishing boom. Today, new children’s literature has appeared in Russia, new authors, new artists, and great Soviet children’s books are being re-printed.

Anthropology for Kids is one of many projects experimenting with a new set of educational tools that attempt to change the status quo in education and the way it shapes our society.

Anthropology for Kids is one of many projects experimenting with a new set of educational tools that attempt to change the status quo in education and the way it shapes our society. It is an open-source methodology and toolkit for academics, teachers, children and artists inspired by the democratic Soviet children’s literature of the 1920s. This particular genre was invented as a means of communicating with the general population in a language that could be shared by everyone. The idea was to build horizontal connections between all participants, and to turn the process of production, reading and distribution of books into a continuous cycle.

My son is now turned 18, so I’ve been working on this project for 12 years – very gradually and intermittently. But most of all I enjoyed our project in Iceland, where in 2019 together with the Icelandic artist and musician Kolbein Hughes we held a series of workshops with children based on the A4kids book What is a Nation. This book was used as our starting point for this open-source collective project, a set of building blocks encouraging those who engage with it to doodle all over it and reimagine their basic ideas of the meaning of “nation” but also – family, school, home, hospital, and so on.

Read Part II of this essay on Thursday….

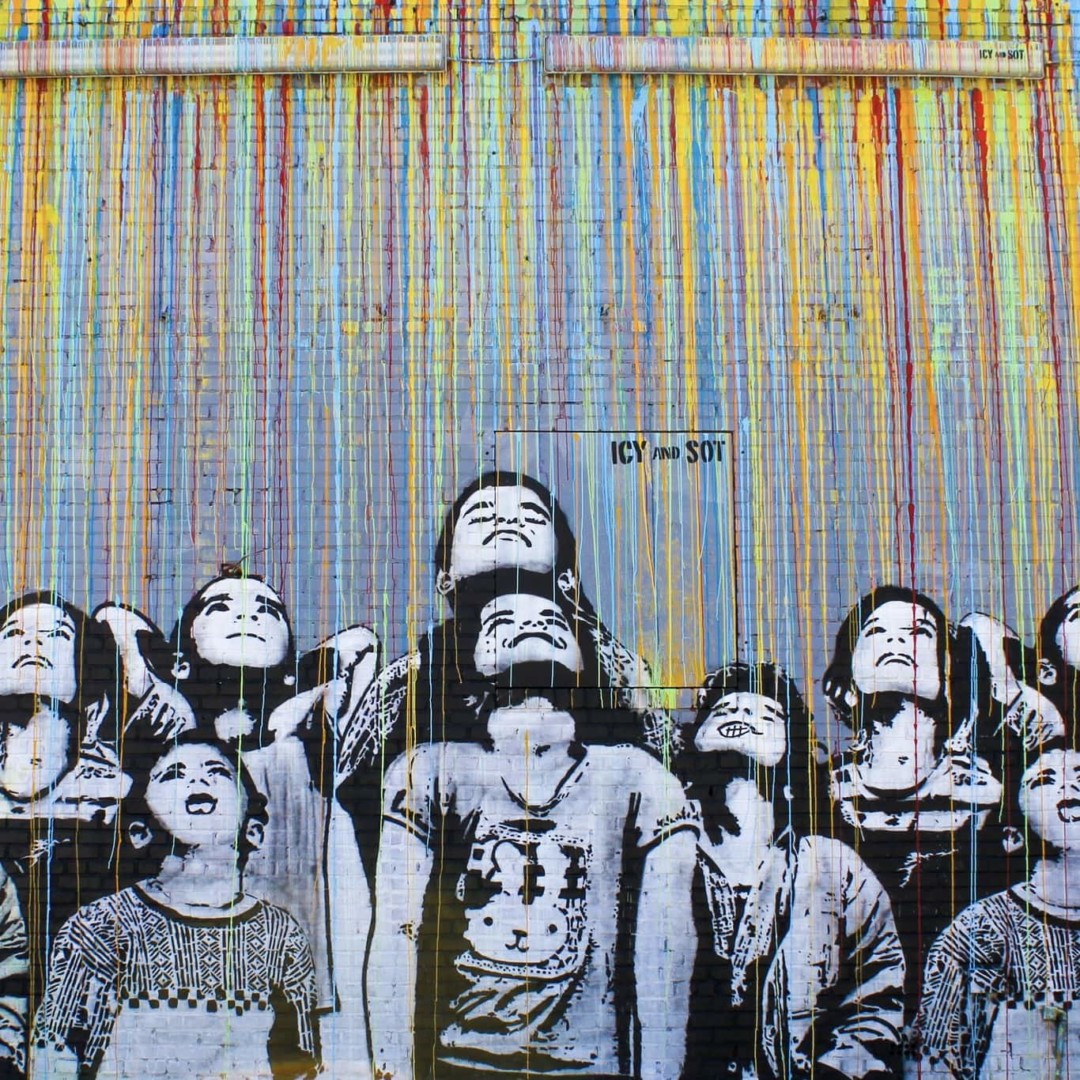

Featured photo by Leonardo Burgos on Unsplash.