I am thrown into an image:

Two figures climbing steep stone stairs, so tall that I cannot see what lies at the top. They are father and son. The father carries a shopping bag in his left hand and walks with a steady but unhurried pace. His son’s footfalls have more bounce, his body more swing, and his hands wander to his fathers hand, then to the railing, and then back again playfully. “It’s so long.” The boy says to his father. “These stairs are taller than the trees!”

“We have to say hello to the dead,” his father replies matter-of-factly. “It’s lonely for them so we have to go say [hello now and then]”.

The towering Japanese cypress, the lush ferns, and even the solemn stone lanterns seem to protect the two with a quiet stillness. Then, tango music begins to play. It sounds like an old phonograph, with pops and scratches and a brassy sharpness. Suddenly we are transported to a room in a Tokyo suburb. Gone are the trees, replaced by the pale pastels of blankets and cushions on and around the reclining bed. Now the father is a son, massaging and flexing his mother’s hips and ankles as she lays back, mouth agape and silent, eyes not registering the scene. Shion, the man’s son, looks on, and his smile is just visible in the close-up shot behind hands and feet.

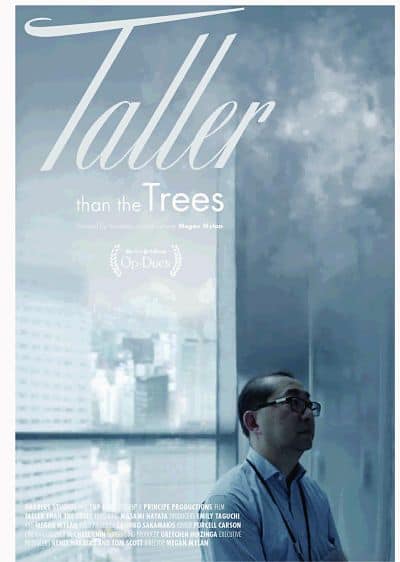

These are the opening images of Megan Mylan’s short documentary feature, Taller than Trees, which premiered on The New York Times website in October. The story focuses on Masami Hayata, a middle-aged salaryman who cares for his frail, bedridden mother at home. His wife, an airline cabin attendant, works for short stretches away from home, leaving Masami to also care for their six-year old child. The cinematography is close and intimate, but also sensitive in a way that struck me as powerfully compassionate. There is no voice-over narration, no dramatic swells of music. The images linger and invite you to imagine what it might be like to be a carer, and a man in Japan’s aging society.

These are the opening images of Megan Mylan’s short documentary feature, Taller than Trees, which premiered on The New York Times website in October. The story focuses on Masami Hayata, a middle-aged salaryman who cares for his frail, bedridden mother at home. His wife, an airline cabin attendant, works for short stretches away from home, leaving Masami to also care for their six-year old child. The cinematography is close and intimate, but also sensitive in a way that struck me as powerfully compassionate. There is no voice-over narration, no dramatic swells of music. The images linger and invite you to imagine what it might be like to be a carer, and a man in Japan’s aging society.

Japan is, by most accounts, facing an eldercare crisis. By 2050, the 65 and older population will be 40 per cent of the total. Strict immigration laws mean fewer people to care for the frail and dependent elderly like Masami’s mother. Everyone in Japan, young and old, will soon be involved in care for an older person. Such close proximity to ageing and dying also means a revaluation of life. Mid-way through the movie, Masami tells us aging isn’t merely a burden, but it is “the natural flow of human life,” a “process” that includes aging, and even frailty and dementia.

The visit to the cemetery in the beginning now makes sense. Masami’s feeling for this flow of life links to the ancestors and to a broader vista of purpose and narrative. Unlike the many investigative journalism-style documentaries that have been produced in Japan about carers, the ethnographic quality of Mylan’s film, its sensitive use of images to tell a story, its ability to link aging and care to generations and spirituality, all captivated me as I watched.

As an ethnographer I could appreciate the attention to the everyday minutiae caught as Masami goes to work, returns, bathes his mother, and the next day takes his son to visit the family dead at the graveyard. In all, the movie follows the family for only two short days.

And in many ways, Masami’s story resembled that of the other male carers that I met during my fieldwork on ageing and family care in Japan over the past three years. Like them, Masami struggled with his identity, suffered health problems from overwork, negotiated over whether to quit his job or stay on, and felt a strong and profound link to the cared-for.

At the same time, the film made me wonder, why are these problems more compelling, touching, or interesting when they apply to a man?

Hasn’t it been the case that women have struggled to manage care responsibilities for much longer, feeling the same push and pull of attachment and grief? Don’t they still make up the greatest proportion of unpaid eldercare in Japan today?

Whenever I present my work on unpaid carers of older people, I almost inevitably get asked the question, “What about gender?” I don’t have to read between the lines too much on this one. Most carers, certainly in the paid sector of ‘affective labour’ (Muehlebach 2011; Hardt and Negri 2001), are women (Broadbent 2010). But the assumption that women have an emotional sensitivity and resilience that make them natural carers makes them uninteresting subjects of a documentary film like Taller than Trees. Instead, we are drawn into the story because we don’t assume that Masami really has the emotional depth and tenderness needed for caregiving, and we are surprised that he can still be an effective businessman at the same time.

As the title suggests, care, for Masumi, means a heroic task of transcending usual gender roles in ways we don’t expect of Japanese men.

And that may be so, but such depictions of male carers (especially those who continue to work) as especially praiseworthy tend to naturalize women’s care and the pressure that Japanese women acutely feel to live up to social expectations to be a good daughter, spouse, or daughter-in-law. Both men and women face an increased burden as Japan moves toward a historically unprecedented demographic shift to a society where 40 per cent of the population will be 65 or older. So as I watch the film, I’m also asking, “What about gender?”

When I mentioned my unease about these inequalities between men and women in their representation as carers to an informant, Fujimura-san, the director of a small NPO (Non-Profit-Organisation) that supports unpaid carers of older adults, she was quick to confirm my sense of the situation, adding, “women have been quitting their jobs to care for ages! But women thought that it was just natural to quit one’s job to care. All the feelings, the guilt and anxiety they feel about care are completely the same [as men]. That’s why I am supporting men’s groups!” Her posture straightened as she said this, and she proudly smiled brightly like a model student trying to get the teacher’s attention.

Japan is a man’s country. So if we don’t make [eldercare] a man’s problem, then the country will never take action. So I am not doing this for women—[care] isn’t really a matter of men or women at all– but if you say it is for men, make it a man’s problem, then the country will take action and women will end up benefiting too. That’s the fastest way to get changes made. I’ve thought about this all very rationally, you see?

Fujimura-san’s insight, drawn from her experience mediating between family carers and political institutions, acknowledged the divide between the reality of carers and the motivations that drive welfare policy. To her, carers have the same basic needs regardless of gender, but men and their problems are the ones that are recognized in the political domain.

The future of ageing in Japan and elsewhere will be determined at the intersection of gender, economics, and policy.

Nowhere is this clearer than in discourses about male carers and job loss (kaigo rishoku). While only about 100,000 people a year quit their jobs in Japan because of care responsibilities, it is estimated that 13 million care, like Masami, while working (the so-called “hidden carers” kakure kaigosha). Between 2000 and 2015 the number of men quitting work to care doubled, a trend that businesses are unable to curtail without government support. The ‘crisis’ of Care Job Losses only took shape as it began to effect men. Even after the proportion of men losing their jobs doubled, women still accounted for at least 80 per cent of those quitting jobs to care. Fujimura-san was well aware of this gendered discrepancy in the government’s reaction to care, and her alliance with men’s support groups, still very genuine, has been an effort to bridge the relatively small but politically significant men to the much larger and marginalized women carers.

Films like Taller than Trees, like good ethnography, transport us into the visual and tactile world of a family carer. But as super-population aging comes into focus across the horizon, we ought to remember not to miss the forest for the trees; our compassion for carers should extend to issues of gender, economics, and policy and the ways these articulations bring about alternative social and political strategies, reorganize gender identities, and build an affinity with ageing and longevity through care.

References

Broadbent, K. 2010. Who Cares about Care Work in Japan? Social Science Japan Journal 13(1): 137–141.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2001. Empire. New Ed edition. Harvard University Press.

Muehlebach, A. 2013. On Precariousness and the Ethical Imagination: The Year 2012 in Sociocultural Anthropology. American Anthropologist 115(2): 297–311.

Mylan, Megan [dir]. 2016 Taller Than Trees. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000004692849/taller-than-the-trees.html

Featured image by Darren Hester (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Eloquent, compelling. I would like to meet the author the next time he is in Japan.