“My best friend from the army was a unit officer responsible for food and supplies. His name was Đura and he was from Serbia. He was two meters tall and everyone was a bit overwhelmed by him. He was also married, had come to serve in the army late and had already had a small child.” This is how Božidar, a retired transport engineer in his sixties started a story of his friend from the Yugoslav military (JNA) when we met in Zagreb over a coffee. He paused, took a deep breath, and continued: “Now, this is what happened with Đura. After one year of service, I went home, and naturally – at the first opportunity I headed to Belgrade to find him. So Đura and I met. There were so many tears, we both cried. We revived our memories… you know, in the army we had shared everything. But then, in 1990, when the war started and Yugoslavia disintegrated, I called Đura. His wife answered the phone. She told me that Đura did not want to talk to me, that all of us Croats were… well… Ustaše, and that he would go to Knin to defend his (Serb) brothers. I tried to talk to him, to persuade him that I was also against many things happening in politics at that moment… To ask him whether he really believed that I could change after everything we had been through in the army… Look, I could not believe what he was saying. We had shared everything. I had met his wife and little kids, and I knew everything about his family. There was no politics there. His name was Đura, my name was Božidar… he was like a brother to me. But then the 1990s came… I was so disappointed. I do not know what happened to him later, whether he went to Knin or not. We have never been in contact again.”

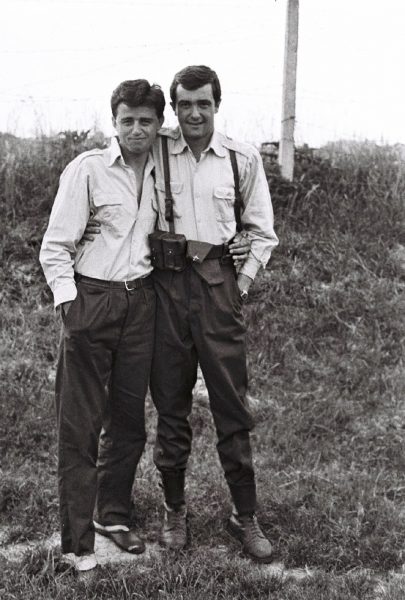

An all-men, total institution like the military, closely related to the notion of hegemonic masculinity, does not seem to be a space where deep, meaningful, and emotionally intense friendships could flourish. This seems even more true of the army in socialist Yugoslavia where all men who turned 18 or graduated from the university had to do mandatory service. Even though the JNA was a military institution where men from all Yugoslav ethnic groups served together and alliances and solidarities were based on moral and personal virtues and not on ethnic belonging, the violent disintegration of the country in the 1990s made such friendships largely impossible and imposed firm associations between the military, masculinity, violence and nationalism. The dominant depictions of men in the Yugoslav space after 1991 are shaped by either nationalist narratives that venerate heroic masculine figures, or by mainstream liberal, normative views on reconciliation that focus on men’s marginal positions of opposing violence and war crimes: draft dodgers, conscientious objectors, peace activists, LGBT activists, and male victims of sexual violence. But such post-Yugoslav framing of men and masculinity leaves aside the experiences of millions of men who were in between these two polarized positions – the men from all corners of the former Yugoslavia who performed army service together and found themselves on the opposite sides once the war began.

It provides no space for the stories like Božidar’s or for the troubled male subjectivities that such stories unfold. These stories of male friendship do not only complicate the understanding of militarized masculinity, echoing Foucault’s (1981) warning that relations based on affection, solidarity, and friendship “at the same time keep [the military institution] going and shake it up.” They also reveal army friendships’ unexpected present-day agency – their capacity to question the seemingly fixed relationship between the past, present and future in the aftermath of socialist Yugoslavia and the violent ethnic conflicts through which it fell apart.

These “impossible friendships,” inconceivable outside the barracks, and the gentle ties established in Yugoslav military uniform, were hardly transferrable to “normal,” ordinary life.

Some of these friendships survived wars, destruction, and displacement in the 1990s. Some men found their army buddies several decades after their service, with the help of the internet and social media. Many friendships, like Božidar’s, did not last any longer than the Yugoslav state and its military. Numerous ties established in the army were never maintained after the service was over. Forged in the confined and limited space of the army base, far away from what used to be normal and everyday life for young Yugoslav men, army friendships were often based on similar character and cultural preferences much more than on shared geographic origin or ethnic background. However, sharing this limited space of the military, away from ordinary life, also made possible a different kind of friendship – those between men of very different backgrounds, as the one between the philosopher Boris Buden and his army friend Jeton from Kosovo. The two soldiers did not even share the same language, but they found a way to enjoy spending time together in free afternoons when they were allowed to leave the barracks and go to downtown Belgrade.

These “impossible friendships,” inconceivable outside the barracks, and the gentle ties established in Yugoslav military uniform, were hardly transferrable to “normal,” ordinary life. The emotional ties between young men on the army base were woven by the slow passage of days, by plenty of time on long, lazy afternoons. And above all, their emotions for each other were shaped by an affective economy of care, a need for solidarity and mutual support among men exposed to the working of a total institution through everyday regimes of drill, discipline, and oppression. At the foundation of these army friendships lay a mutual recognition of men in universalist terms, as moral and virtuous humans, as “good men”.

Several decades after the Yugoslav wars, social media are abundant with posts about reunions of men who used to be friends in the military. On March 4, 2019, one of the Serbian Internet news portals published an article about two friends from the Yugoslav army, a Serb, Branislav Ković from Bogatić, and a Croat, Ivica Krajina from Đakovo, who met again for the first time after 1984, when they had served together in the JNA in Pirot in southern Serbia. The article reports that Ivica and Branislav have often thought of each other during all these years, especially after the war started and the old country fell apart. “Of course, we also talked about divisions, war, and the dissolution of Yugoslavia,” reported Branislav and Ivica on their reunion. “As mature and serious persons, we respect that each of us loves his country and nation. Such a degree of nationalism does not harm our friendship.”

The encounter of these two men would not have become media news if they had not been a Serb and a Croat. Such news confirms the completion of the process in which people’s biographies were reduced to a single trait: their ethnic identity and the adjacent religious ones. They became Croats, Serbs, Albanians, Slovenians, Muslims, Catholics, Orthodox… They were killed, beaten, expelled, displaced, threatened, erased from official records, or put in concentration camps because of what they were. And they were killing, beating, expelling, threatening, or burning houses of others because of what they were. In her recent book, Mila Dragojević provides an account of this process of becoming, zooming in on the formation of ethnically based communities of Croats and Serbs in wartime Croatia, 1991–1995. She defines these newly fixed frames of belonging as amoral communities, singling out as their important characteristic the fact that “the connection between ethnicity and political identity extends into everyday facets of life.” In such communities, “instead of perceiving each other in terms of personal traits or community roles, people first consider ethnicities” (Dragojević 2019: 3). This logic of recognition and organization does not only flatten individual biographies, but also significantly closes political horizons: as Dragojević pointed out in an interview, amoral communities are “places where individuals don’t feel free to express their personal views if those views don’t align with one of those dominant views or narratives [of their perceived ethnic group].” In such places, “a person of a certain cultural identity automatically has certain political views and one doesn’t give them any space to think otherwise.”

Their afterlife in the post-Yugoslav reality, manifesting as a force to contradict, question, unsettle, and trouble what is given, normalized and taken for granted, unfolds from silence, suspension, hesitation, uncertainty and impossibility.

Recalling recognition and solidarity based on moral and personal qualities, friendships made in the Yugoslav army contradict and question this ethnicized logic of structuring reality established through the Yugoslav wars and normalized in the decades that followed. But their afterlife in the post-Yugoslav reality, manifesting as a force to contradict, question, unsettle, and trouble what is given, normalized and taken for granted, does not lie in what is explicit, preserved, revived, maintained and said. Instead, it unfolds from silence, suspension, hesitation, uncertainty and impossibility.

In the late 1990s, after the wars in Croatia and Bosnia ended, and before the NATO intervention in Serbia and the violence in Kosovo, Mitko Panov, a Macedonian-Swiss director and a former JNA soldier who had completed his service in Titov Veles in 1981 and left for the US to pursue a career of an artist, came back to his homeland with a particular goal: to find out “what had become of [his] army buddies, did they find themselves carrying weapons again? Did they have to use them against each other? Who prospered and who was caught in the tangles of the war?” Looking for the men with whom he had shared a year in the JNA uniform, Panov traveled through landscapes laid to waste, across newly established borders controlled by the international forces trying to prevent new outbreaks of conflict. This was a devastatingly painful journey, and it is painful to watch the documentary he made of it. Reaching addresses where his army buddies were supposed to live, he finds burned houses, ethnically cleansed towns and villages, and his friends missing, dead, displaced, economically struggling, with ruined health and ruined lives. In the course of his quest for his friends from the army, Panov abandons his original idea of finishing the film and journey with a reunion party for his army buddies, because it was impossible to recreate a moment in which the future still seemed possible and bright from the confined space of the barracks in Titov Veles.

This possibility of a different future is a driving force that makes these impossible, unreconstructable friendships still alive and important.

This possibility of a different future is a driving force that makes these impossible, unreconstructable friendships still alive and important. These friendships live on in the present as a lingering reminder of this future past (Koselleck 2004). They are revealed in Božidar’s incapability to accept the fact that his friend rejected him only because they come from two ethnic groups; in a special place some of the former Yugoslav soldiers keep photos of an army friend whom they had never seen after their service was over; in a long lasting desire to reach out and contact the best friend from the army that never becomes realized; in the hesitant, but persistent questions Kadri, an Albanian from Kosovo, poses to Mitko Panov about the destiny of Dragan, a Bosnian Serb with whom they were very good friends back then in Titov Veles.

These impossible, discontinued friendships have the capacity to destabilize what seems to be an unquestionable narrative about the past and the present that has no alternative in the post-Yugoslav reality.

These impossible, discontinued friendships have the capacity to destabilize what seems to be an unquestionable narrative about the past and the present that has no alternative in the post-Yugoslav reality. They are capable of questioning, disrupting, and complicating selves, biographies, and the temporal frames in which they are situated. The existence of a man who was a friend, somewhere else in another former Yugoslav republic that is now an independent state, constantly reminds one of a world gone and made impossible through wars and violence in the 1990s and of different, but irrevocably vanished, possible futures.

References

Dragojević Mila. 2019. Amoral Communities: Collective Crimes in the Time of War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Foucault, Michael. 1981. “Friendship as a Way of Life,” https://caringlabor.wordpress.com/2010/11/18/michel-foucault-friendship-as-a-way-of-life/, an interview R. de Ceccaty, J. Danet, and J. Le Bitoux. Gai Pied.

Koselleck, Reinhart. 2004. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. New York: Columbia University Press.

Panov, Mitko. 2000. Comrades. USA/Macedonia (film).

Featured image (cropped) by Fotocitizen (courtesy of Pixabay)