Treasures and Discreet Afterlives of Greek Heritage in Contemporary Turkey

Treasure hunts have long been a common practice, constituting one of the primary problems for heritage preservation in contemporary Turkey and elsewhere (see Bachhuber 2019, Hamilakis 2003). Hunters have dug, defaced, blasted, and blatantly destroyed historical artifacts across the country with the hopes of finding a treasure that they could cash in. Although they have mostly targeted ruins and graves, natural formations have not been spared if they were thought to stand in between the hunters and the presumed trove. In late 2019, one such hunting party apparently solicited the official permit for their quest to find a “treasure”, allegedly left behind by one of the Roman legions in northeast Turkey. Puzzlingly, though, where they worked on with industrial-size excavators was not an archaeological site with ruins of Roman-era barracks or, say, a castle. The hunters targeted a lake, called Dipsiz Göl [lit. Bottomless Lake], which they believed to be an artificial body of water concealing the Roman riches they searched for.

Although geologists indicated that the lake had been formed by glacial movements around 12.000 years ago, hunters were unanimously convinced that it was a man-made cover for the troves lying underneath. Despite the protests of conservationists, the hunting party went ahead with their quest to drain the entire lake and to excavate further down but, unsurprisingly, found nothing. Once the excavation ended, it became evident that the lake would probably never recover.

Although much can be said about the destructive implications of treasure hunts on archaeological remnants, I will focus on how “natural” (Çaylı 2015; Latour 2004) interfaces are targeted through treasure hunts and their potential causes. Drawing on an ethnographic research I conducted in in northeast Turkey, in 2012-2015, I explore everyday engagements with treasures to understand what imaginations and narratives of treasures may reveal about the afterlives of abjected cultural heritages:

Why do communities imagine treasures in seemingly natural spaces (e.g. lakes or mountains), to begin with? How is such information socially circulated despite lacking material evidence? And more importantly, which social processes fuel such imaginations of treasures across local landscapes?

Attending to these questions, I explore the afterlives of cultural heritages following the socio-political ruptures in the early 20th century, when non-Turkish communities (primarily Greeks and Armenians in the case of the Black Sea littoral) were violently destroyed to forge a homogeneous Turkish national identity. The communities I worked with in Trabzon, in northeast Turkey, are ardent Turkish nationalists and yet continue to speak, albeit discreetly, an archaic variety of Greek that was long presumed to be dead. My take on afterlives, hence, departs from the amnesiac turn Turkey took in the early 20th century and focuses on its reverberations across topographical, “corporeal, mnemonic, and sensory engagements between people” (Cherry 2013, 3) and the places they dwell. Here, afterlives in a plural form (Cherry 2013) also pertain to the way cultural heritages persist and transfigure in relation to wider socio-political ruptures and displacements as well as how publics engage with these incessant transfigurations to issue forth new modalities of being, belonging, and remembering (Fassin 2015). Through the case of the unexpected survival of Greek that my interlocutors held dear and yet kept private, my exploration of everyday engagements with treasures in contemporary Turkey pertains particularly to the ways non-Turkish languages have “lived on” and invites the reader to attend to their survival in different forms. I pursue how Greek heritage, despite politico-legal interventions to obliterate it, discreetly (Mahmud 2014) “lives on” across local topographies, enchants these intimate places, and marks the communal boundaries in today’s Trabzon.

I take “engagements with treasures” as a range of practices that involve (i) narratives on buried/concealed troves probing their mythical/historical origins, whereabouts, content, and current (economic) value as well as how to access them; (ii) solicitation of “documents” indicating the location of troves, and more rarely (iii) the organization of hunting parties and, rarely, their unearthings. These narratives are not necessarily limited to verbal accounts but also include dreams, specters, and myths that often defy rational, coherent articulations. Rather than readily dismissing treasure hunts as destructive practices striving for material riches—given their strong appeal despite their overall fruitlessness, this piece suggests juxtaposing the social imaginations of treasures across seemingly natural interfaces with socio-historical genealogies of the landscapes to rethink their psychosocial interconnectedness (Saglam 2019). I would suggest also exploring how seemingly non-material traces in the form of imaginations, magicalities, specters and hauntings (Frosh 2013; Gordon 2008), and dreams are implicated in social forgings of these narratives, which may help us rethink the possibility for non-discursive, affective, and “topographical” (Knight 2017, 29) remembrances and relations with the past.

As I started my ethnographic research in northeast Turkey in 2015, I primarily pursued the question of how rural communities scattered across this geographically secluded and elevated valley (henceforth, the Valley) reconciled their preservation of a variety of Greek with archaic linguistic features, called Romeyka (Rumca in Turkish) (see Saglam 2020) with their strong support for Turkish nationalism. Relying both on conventional ethnographic methods and oral history, I explored how this discreet presence of Greek reverberated across my interlocutors’ identities as well as their relations to the past and places they dwelled in. Through the course of my research, I also noted that most of my interlocutors—often men due to customs regarding the relations between sexes—often talked about (Greek) treasures buried here and there across the Valley. While collecting data both on the (communal) privacy of Greek and the prevalence of narratives of treasures, I started thinking about the interrelationship between the two. I first detail how Romeyka “lives on” in the Valley despite all odds and how my interlocutors engaged with treasures to ask further questions about the afterlives of this idiosyncratic cultural heritage.

Historical data indicate that the settlements across the Valley emerged as Greek-speaking Christian villages in the late 15th century and gradually converted to Islam—without experiencing a language shift to Turkish (see Lowry 2009, Meeker 2004). Even though Trabzon had a vibrant Greek community till 1920s, Greek heritage was thought to have been uprooted from the region with the Greco-Turkish population exchange in 1923, obliging (Christian) Greek-speaking communities to leave Turkey for Greece. As the population exchange took religion as the only criterion, this idiosyncratic variety of Greek, which is linguistically more archaic than the Pontic variety spoken by Christian communities in the area until 1923 (see Sitaridou 2014), could survive among secluded (Muslim) communities in Trabzon up to today. Subsequently Turkish nationalism precluded the use of any non-Turkish languages (especially the ones it is particularly antagonistic to, e.g. Greek and Armenian). Since then, Greek has long been presumed to be extinct in contemporary Turkey, except the dwindling communities in Istanbul and Imbros.

Discreetly living on despite these nationalist erasures across mountainous villages, Romeyka has been transmitted solely within families and has no writing system. The language is currently used for intimate familial, communal, agricultural and local matters. Since Valley communities are ardent Turkish nationalists, they passionately distance themselves from Greek heritage and refrain from using the language in public. Greek, hence, is secluded to intra-communal encounters with its public visibility carefully controlled through shifting to Turkish in the presence of outsiders or using misnomers to conceal (Herzfeld 1997) its connection to Modern Greek.

Discreetly permeating the social lives of the Valley communities, Greek nevertheless emerges an indispensable element of communal identity which has been kept alive through its banishment from public.

This seclusion of Greek to intra-communal encounters, however, does not mean that it has lost its socio-cultural significance, nor have the communities completely dispensed with the Greek heritage. Although my interlocutors almost unanimously claimed Turkic lineage (often from the Central Asia), they also circulated their family genealogies and Greek patronymics in private. Furthermore, defying the state policy to Turkify the geography which has assigned Turkish names to major geographical marks (Öktem 2008), men and women of all ages still use centuries-old Greek toponyms for villages, neighborhoods, estates, mountains, pastures, woods, rivers and similar other topographical features, generating a detailed map of the Valley that only the local communities know of. Greek, in this sense, emerges as the intimate, familial, and communally private medium through which local men and women relate to and move across the Valley.

This seclusion of Greek to intra-communal encounters, however, does not mean that it has lost its socio-cultural significance, nor have the communities completely dispensed with the Greek heritage. Although my interlocutors almost unanimously claimed Turkic lineage (often from the Central Asia), they also circulated their family genealogies and Greek patronymics in private. Furthermore, defying the state policy to Turkify the geography which has assigned Turkish names to major geographical marks (Öktem 2008), men and women of all ages still use centuries-old Greek toponyms for villages, neighborhoods, estates, mountains, pastures, woods, rivers and similar other topographical features, generating a detailed map of the Valley that only the local communities know of. Greek, in this sense, emerges as the intimate, familial, and communally private medium through which local men and women relate to and move across the Valley.

In addition to this social significance of Romeyka, communities had other intriguing ways to continue recognizing and engaging with the Greek heritage in the present. Most of my interlocutors, of different socio-economic status, mentioned a treasure left (by Greeks or others) behind/beneath seemingly natural features in rather familiar and intimate places around the Valley. Woods nearby one interlocutor’s village were said to have overgrown a long-deserted house with treasures buried beneath, while a hilltop was rumored to be a castle with a number of chambers carved inside the mountain housing riches. Dreams were often integral elements of these accounts since the location and the content of troves were “revealed” through them. Sightings of cins—djinns, the supernatural beings in Islamic mythology—were, similarly, mentioned as a proof of the existence of a treasure nearby. Most of my interlocutors explained the overall fruitlessness of treasure hunts in reference to cins: the treasures were often said to be possessed [cinli or sahipli] by cins and took many deceptive forms to elude the hunters. To overcome these obstacles, I was told, many hunters have cooperated with Greeks (and sometimes Armenians), who would recite a prayer in Greek (or Armenian) to break the haunting curse.

In addition to this social significance of Romeyka, communities had other intriguing ways to continue recognizing and engaging with the Greek heritage in the present. Most of my interlocutors, of different socio-economic status, mentioned a treasure left (by Greeks or others) behind/beneath seemingly natural features in rather familiar and intimate places around the Valley. Woods nearby one interlocutor’s village were said to have overgrown a long-deserted house with treasures buried beneath, while a hilltop was rumored to be a castle with a number of chambers carved inside the mountain housing riches. Dreams were often integral elements of these accounts since the location and the content of troves were “revealed” through them. Sightings of cins—djinns, the supernatural beings in Islamic mythology—were, similarly, mentioned as a proof of the existence of a treasure nearby. Most of my interlocutors explained the overall fruitlessness of treasure hunts in reference to cins: the treasures were often said to be possessed [cinli or sahipli] by cins and took many deceptive forms to elude the hunters. To overcome these obstacles, I was told, many hunters have cooperated with Greeks (and sometimes Armenians), who would recite a prayer in Greek (or Armenian) to break the haunting curse.

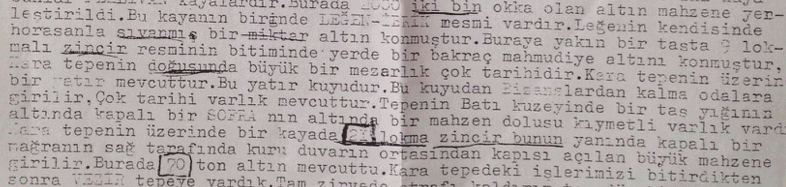

Convinced of detecting “signs” of such troves buried across their villages, neighborhoods, and estates, some interlocutors occasionally took me to these “signs” or showed their photos so that I—often due to the homonymic affinity between anthropology and archaeology—could help them decipher the location of treasures left behind by past communities. In most cases, the “signs” I was shown presented no discernible figure—at least as far as I could see—and were more likely to be natural formations.

And yet, my informants were convinced that they were indeed man-made traces deliberately left there to guide the descendants of past communities to the buried riches.

The proximity of these “signs left behind by others” to their ancestral villages, which they claimed to have inhabited for centuries, was not of concern. Some even contemplated the existence of Greek troves within their own houses even though they publicly claimed that their Turkish family had inhabited that particular house since time immemorial.

How are we to understand this social imagination of treasures across the Valley across seemingly natural interfaces? How is the discreet preservation of Greek interrelated with the imagination of traces of past communities—especially Greeks—in intimate sites even though locals publicly disassociate from the Greek heritage? What does locals’ imaginings of “signs”, treasures, and specters across the landscapes, then, tell us about the afterlives of the cultural heritage that was destined to wither away?

Since narratives of treasures are widely circulated despite their almost unanimous fruitlessness, the importance of these narratives and hunts, I argue, may lie in the very ways they engage unaccounted, abjected memories in spectral, affective, magical, and topographical forms. Even though my interlocutors ardently deny the socio-historical presence of Greeks within the contours of the Valley (in line with their support for Turkish nationalism), narratives of and hunts for Greek treasures across their ancestral villages affirm the Greek heritage of the Valley and the communities inhabiting it. The narratives incessantly resuscitate the memory of Greeks (and others) across intimate spaces as if they “have an ongoing presence” (Gordillo 2014, 36).

These engagements with treasures may be seen as spectral, corporeal, and topographical engagements with the banished cultural heritage.

Places that people dwell in, then, may preserve and animate abjected fragments of collective memory through a diverse range of implicit and often incoherent engagements that may at first seem senseless and rather destructive. As these fragments remain unaccounted and “incorporated”, albeit in muted forms, into the local topographies, communities may very well be “acting out” (Freud 1995 [1914]), transforming the abjected memory into practices, narratives, imaginations through which they keep on engaging with it in different modalities. When the nationalist matrix stipulates the foregoing of Greek (heritage) for one to assume their position as a Turkish subject, for instance, communities had to maneuver across the politico-legal prerequisites of Turkish citizenship and the socio-cultural practices that made up the very kernel of communal identity. As the language was precluded from the very definition of Turkishness and was destined to die out, however, it did not simply wither away but may have very well been transfigured into different versions with different functions that are further amended through replications and reinterpretations. Today, Romeyka, as I indicated above, marks communal extents, carries family genealogies, and mediates community’s relations to the places they dwell in as well as providing the community with a detailed mapping of the Valley.

Its afterlives, in this sense, not only strive to “live on” against all odds but instantiate different senses of place through engendering specters and “signs” across intimate sites.

Afterlives of cultural heritages, in this sense, are intricately linked to specters that “do not sit still” and “crack through pavements” (Tsing 2017, 8) across homely spaces to haunt our social lives, to evoke affects, and to take new forms. Tracing their transfigurations reveals how memories persist and live through erasures, multiply into both spectral and topographical forms, and get re-worked to assume new meanings and relations. These reworkings seem to involve a diverse range of imaginations, desires, narratives, and practices that are brought to the public through the mediation of material and immaterial means. What remained historically unaccounted in the case of the communities living by Dipsiz Göl, for instance, may have very well been implicated in the generation and circulation of treasure-narratives. Although it seems both insensible and illogical to outsiders, the very plausibility of a trove beneath a lake or inside a hill, for many, may be appealing enough because of these very imaginations, myths, and specters evoked by cryptic residues across our social lives. Understanding how natural interfaces are narrated to hold treasures, in this sense, requires us to be attuned to the afterlives of heritages and memories.

SOURCES CITED

Argenti, Nicolas. 2017. “Introduction: The Presence of the Past in the Era of the Nation-State.” Social Analysis 61 (1) 1-25.

Bachhuber, Christoph. 2019. “The Lion Pit and Other Ambiguous Violence against Statues at Iron Age Zincirli.” In Visual Histories of the Classical World: Essays in Honour of R.R.R. Smith, by C Draycott, R Raja and K Welch, 77–86. Brepols: Turnhout.

Basso, Keith H. 1996. “Wisdom Sits in Places.” In Senses of Place, by Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso, 53-90. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Bieberstein, Alice von. 2017. “Treasure/Fetish/Gift: Hunting for ‘Armenian Gold’ in Post-genocide Turkish Kurdistan.” Subjectivities 10 (2) 170-89.

Biner, Zerrin Özlem. 2010. “Acts of Defacement, Memories of Loss: Ghostly Effects of the ‘Armenian Crisis’ in Mardin, Southeastern Turkey .” History and Memory 22 (2) 68-94.

Casey, Edward S. 1996. “How to Get from Space to Place in a Fairly Short Stretch of Time: Phenomenological Prolegomena.” In Senses of Place, by Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso, 13-52. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Cherry, Deborah. 2013. “The Afterlives of Monuments.” South Asian Studies 29 (1): 1-14.

Çaylı, Eray. 2016. “’Accidental’ Encounters with the Ottoman Armenians in Contemporary Turkey.” Études Arméniennes Contemporaines 6 257-270.

Fassin, Didier. 2015. “The Public Afterlife of Ethnography.” American Ethnologist 42 (4): 592-609.

Frosh, Stephen. 2013. Hauntings: Psychoanalysis and Ghostly Transmissions. London: Palgrave.

Gordillo, Gastón. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. London: Duke University Press .

Gordon, Avery F. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Hauntings and the Sociological Imagination. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Hamilakis, Y. 2003. “Iraq, Stewardship and ‘the Record’: An Ethical Crisis for Archaeology.” Public Archaeology 3 (2) 104–111.

Herzfeld, Michael. 1997. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. London: Routledge.

Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University.

Lowry, Heath W. 2009. The Islamization and Turkification of the City of Trabzon 1461-1583. Istanbul: The Isis Press.

Mahmud, Lilith. 2014. The Brotherhood of Freemason Sisters: Gender, Secrecy, and Fraternity in Italian Masonic Lodges, . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Meeker, Michael. 2002. A Nation of Empire: The Ottoman Legacy of Turkish Modernity. London: University of California Press.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2012. The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity,. Durham: Duke University Press.

Öktem, Kerem. 2008. “The Nation’s Imprint: Demographic Engineering and the Change of Toponymes in Republican Turkey.” European Journal of Turkish Studies 7 [Online: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejts.2243].

Saglam, Erol. 2019. “Bridging the Social with What Unfolds in the Psyche: The Psychosocial in Ethnographic Research.” In New Voices in Psychosocial Studies, by S. Frosh, 123-39. London: Palgrave.

– 2020. “Commutes, Coffeehouses, and Imaginations: An Exploration of Everyday Makings of Heteronormative Masculinities in Public.” In The Everyday Makings of Heteronormativity, by S. Sehlikoglu and F. Karioris, 45-63. London: Lexington.

Sigmund Freud. 2003 [1919]. The “Uncanny” [Online: https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf].

Sitaridou, Ioanna. 2014. “The Romeyka Infinitive: Continuity, Contact and Change in the Hellenic Varieties of Pontus.” Diachronica 31 23-73.

Stewart, Charles. 2003. “Dreams of Treasure: Temporality, Historicization, and the Unconscious.” Anthropological Theory 3 (4) 481-500.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2008. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23 (2) 191-219.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

ONLINE SOURCES

“Dipsiz Göl ile İlgili Savcılık Soruşturması.” Sözcü website. Available online at: https://www.sozcu.com.tr/2019/gundem/dipsiz-gol-ile-ilgili-savcilik-sorusturmasi-5480287/

Romeyka website. [https://www.romeyka.org]

“Treasure Hunters Destroy Ancient Lake in Northeastern Turkey.” Ahval News. Available online at: https://ahvalnews.com/turkey-ecology/treasure-hunters-destroy-ancient-lake-northeastern-turkey

IMAGE SOURCES

Featured Image via Good Free Photo, unknown author, CCO

Dipsiz Göl before and after the “treasure hunt” (Source:online newspaper Sözcü Gazetesi)

Landscapes near Trabzon (Turkey): Images by Abdullah Muashi found on Flickr here and here (CC BY 2.0)

Text Fragment Image by Erol Saglam, in Trabzon

Screenshot of Definelyyou Forum taken by Erol Saglam

This post is part of the #Afterlives thread, for which we already published #Afterlives: Introduction, #Afterlives: Shaheen Bagh and the Force of Foundation, and Haunted: Spirits and the Agency of the No Longer in Niger #Afterlives